According to the Basic Law, Hungary bears no responsibility for what happened from the day of the German occupation (19.3.1944) until the change of system (2.5.1990). The bloodbath committed by Hungary 80 years ago does not fall within this period.

On 25.3.1941 Yugoslavia – under German pressure – joined the Three-Power Pact; the next day the Yugoslav army revolted against it. Hitler, who was busy preparing for the war with the Soviet Union, also wanted to solve the problem of the Italian defeats in the war with Greece. Thus, a blitzkrieg against Yugoslavia and Greece was planned on short notice and Hungary was required to participate.

In November 1940 the Teleki government had signed the “Treaty of Eternal Friendship” with Yugoslavia and this put the Prime Minister, who had been trying to maintain a neutral foreign policy, in a serious dilemma. If he resisted Hitler’s demands, he would not get back former Hungarian territories, But if he accepted the offer, he risked conflict with Britain. There was also the moral issue of violating the friendship pact with Yugoslavia. The Catholic Prime Minister Teleki, seeing no way out of the situation that had become insoluble for him, committed suicide on 3 April. His successor, László Bárdossy, had no qualms. For although Hungary had not taken part in the war against Poland in 1939, it was able to regain part of the territories lost in 1918 through its close friendship with Germany.

In mid-April 1941, Hungarian troops took part in the dismemberment of Yugoslavia and conquered the Batschka, a region with a mixed population (Hungarians, Serbs, Croats, Germans, Ruthenians, Slowaks, Russians and Jews).

At the beginning of the occupation there was a massacre in the village of Temerin, where the invading Hungarians massacred several hundred Serbs waving white flags. Tens of thousands of Serbs who had moved to the Batschka after 1918 were expelled to German-occupied Serbia, and many thousands of Hungarians were settled.

After the German failure to capture Moscow, minister for foreign affairs Ribbentrop visited Budapest in early January 1942 and demanded the participation of the entire Hungarian army in the war against the Soviet Union and to legalise recruitment of ethnic Germans to the Waffen SS, which had been tacitly tolerated until then. Hungary agreed to this demand, but they objected that the army was needed to fight the partisans who had infiltrated from the German-occupied neighbourhood. It was only after the attack on the Soviet Union that the Yugoslav Communist Party organised a partisan movement which, despite many executions and prison sentences, could not be brought to a halt.

Subsequently, following an agreement with the Wehrmacht in the Banat, there was a coordinated action to “establish order” in the Batschka. The Hungarian troops committed a massacre right at the beginning. Entire Serbian families were murdered and sunk under the ice of the Tisza or the Danube. In Zsablya and Csurog alone, to name only the two villages most affected, there were at least 1,540 victims of the operation, including 265 women, 43 children and 143 elderly people.

On 12 January 1942, Lieutenant General Ferenc Feketehalmy-Czeydner, commanding in the Batschka, falsely informed his superiors that the partisans had retreated to Novisad (Ujvidék). On 20 January, Hungarian troops closed in on the town. Martial law was declared. On 21 January, a massacre by Hungarian army, border guard and gendarmerie troops began and lasted until 23 January.

On the first day of the raid, people were indiscriminately taken to the Danube bank and executed. Colonel József Grassy encouraged his subordinates and stressed that it was “retaliation”. He ordered troops “to machine-gun the streets”; and “to clean up all the filth in the city, it must float in the Danube”. Feketehalmy-Czeydner and Grassy were not satisfied with the result of the first day, with the 50-60 dead.

On 22 January, the purge continued. To boost the morale of the crew, a “fake partisan battle” was staged with Serbian weapons and hand grenades next to two civilian corpses. Rum was distributed to the units to keep up their “fighting spirit”. Feketehalmy-Czeydner openly declared that he wanted to see “corpses”. The rounded-up victims had to strip naked on the banks of the Danube at -20 degrees Celsius and were mowed down with machine guns, but people were also shot in flats and on the streets.

Colonel Grassy, thanks to the strong protest of the mayor, gave the order to end the raid at 9pm on the evening of 23 January. But he threatened the town that the calm would cease if another “enemy gun was fired” or there was a “partisan or other anti-national plot against the Hungarian state”. In the following days, there were further raids in the area until Chief of General Staff Ferenc Szombathelyi had the operation stopped on 30 January 1942.

Historians put the number of victims at 4,000, of whom 1,250 were Jews. Among the victims there were 792 women and 147 children. In Novisad, most of the victims were Jews.

News of the massacre made waves at home and abroad. Hungarian opposition members protested and demanded an investigation. The anti-fascist MP Endre Bajcsy-Zsilinsky intervened repeatedly in parliament and submitted a 25-page memorandum to the Head of State Horthy on 4 February 1942. In order not to stain the “honour of the army”, Horthy had the investigations against members of the army stopped. Feketehalmy-Ceydner and Grassy (promoted to Major General on 1.4.1942) were retired.

As early as April 1943, secret negotiations took place between Hungary and Great Britain in Ankara, where the Hungarian envoy admitted that “the local commanders ordered the mass slaughter of Serbs and Jews and allowed free robbery … a unique event in the history of Hungary.”

In October 1943, the investigation against Feketehalmy-Czeydner and accomplices was reopened. The military prosecution finally presented an indictment against those responsible for the massacres, on the basis of which the main trial began on 14 December 1943. However, the main accused were not arrested and were able to flee to Germany in January 1944, where they were granted political asylum by Hitler himself. They returned to Hungary two months later in SS uniforms and participated in the deportation of Jews.

In March 1946, the main accused were sentenced to death by the Budapest People’s Court and extradited to Yugoslavia. On 24 October 1946 the trial of nine accused began in Novisad. Six days later they were sentenced to death and executed.

Dr. Sándor Szakály, the director of the Veritas Historical Institute appointed by the Orbán government, said: “After the return of the South, Serbian partisan actions intensified because they did not accept the annexation of the area to Hungary. In order to put a stop to this, the Hungarian defence forces carried out a crackdown, which also resulted in the death of innocent people.”

This cynicism is indicative of the state’s rewriting of history in Hungary.

History is a powerful weapon. It is particularly dangerous in the hands of chauvinist nationalists who want to shape history. It must be countered so that the world – present and future generations – can learn its lessons and thereby avoid another catastrophe.

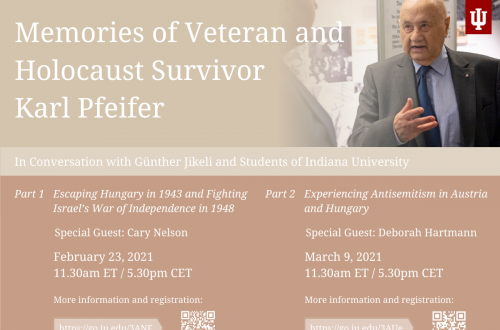

Guest post by Karl Pfeifer