Gene’s expose of the BBC’s removal of the word ‘terrorist’ from its online reports has received wide coverage in the media including yesterday’s Jerusalem Post and today’s edition of The Times. There are a couple of points made by other bloggers on this issue that I want to point to:

Firstly, Norm makes the vital point that terrorism has a precise meaning:

Terrorism, which involves the deliberate targeting of civilians with a view to killing and maiming them and if possible in large numbers, is a crime against humanity under international law. It is not, consequently, a partisan matter to refer to terrorists as ‘terrorists’. It is simply to fall in with a moral standard already recognized as universal in human rights thinking and legislation. If the BBC regards the term as overly judgemental, why do they not have similar taboos or coynesses with regard to ‘torture’? Shouldn’t this, too, be spoken of more neutrally as ‘pressure’, ‘questioning’, or what have you? Even ‘genocide’ can be sanitized with less direct words.

Oliver Kamm also hits the nail on the head, dismissing the issue of BBC ‘bias’, he says:

The problem is that the BBC is oblivious of the first requirement that journalists, subject to partial information and subjective assumptions as they are, nonetheless describe the world as it is. The BBC’s priority, by contrast, is to try to avoid disturbing the sensibilities of its viewers and listeners. The most reliable way to accomplish that end is to introduce language that so far from eschewing ‘value judgements’ merely fails to discriminate among them.

The noun ‘bomber’ might refer to the murderers of 52 civilians in London, whom all civilised people execrate, or to the airmen who flew missions into Germany in WWII, whose heroism we have celebrated this week. The noun or adjective ‘militant’ might refer to political violence or it might refer to a strictly verbal form of protest. Listeners can pick and choose what interpretations they like; but what is lost is anything resembling journalistic precision.

Someone who expresses his political opinions immoderately but non-violently is not the same type of activist (to use another catch-all phrase favoured by the BBC) as someone who explodes a bomb on a rush-hour bus. As the international historian Walter Laqueur observes in his study of modern terrorism No End to War (pp. 236-7)

“To call a terrorist an ‘activist’ or a ‘militant’ is to blot out the dividing line between a suicide bomber and the active member of a trade union or a political party or a club. It is bound to lead to constant misunderstanding. ”

That is the point: the BBC is guilty of bad journalism that betrays the corporation’s purpose of advancing public understanding.

I’ll just add one thing – whenever I have discussed this matter the phrase that always appears at some stage in the conversation is “one man’s terrorist, is another man’s freedom fighter”.

But if terrorism has a meaning (and it does as Norm shows) then that argument becomes irrelevant. Terrorism is a method, a tactic, an action. It would have been entirely correct, for example, if the ANC had blown up a hotel in Sun City to describe that act as terrorism because it would have been the deliberate targeting of civilians with a view to killing and maiming them and if possible in large numbers. To label that act as terrorist would not pass any judgement on the cause in which the act was carried out, would not have involved taking sides in the South African conflict, but would merely have been an accurate description of the act.

The tricky part comes in labelling particular movements or organisations or as terrorist. A group which uses violence aimed exclusively at military targets – is not a terrorist group. There are other groups who target both civilian and military targets for whom a more nuanced description could be justified. And there are groups which routinely carry out acts of terrorism, who exist for that purpose, who can obviously be referred to as terrorists. But by removing terrorist from the vocabulary, the distinction is at risk of being lost.

This area of argument has no impact however on the question of how to describe last week’s atrocities in London. There is not the slightest doubt that the bombs were acts of terrorism the BBC and other media outlets should have had no problems in describing them as such.

Like Oliver, I don’t think the BBC’s reluctance to use the ‘t word’ indicates any bias on their part. I certainly don’t subscribe to the view that this affair shows that the BBC is ‘soft on terrorism’ or has any sympathy with the terrorists. It is a journalistic confusion born of an ill-advised editorial policy and one which is by no means unique to the BBC.

But I will make a hunch as to one of the factors that is behind this mistaken approach.

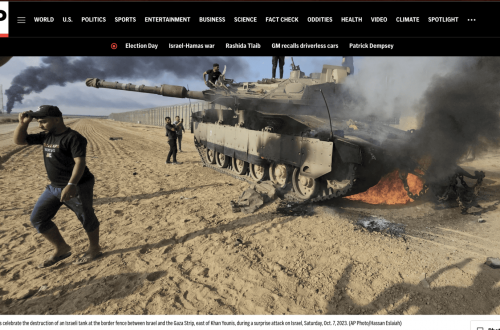

It is in the reporting of Palestinian terrorism that we first noticed the parade of euphemisms, most notably ‘militant’. The desire to be seen as even-handed in coverage of the Israel-Palestine conflict, a completely worthy and indeed necessary objective, led to a reluctance to describe terrorism as terrorism. Yet the word is completely accurate and appropriate to describe, for example, suicide murders carried out in pizza parlours and cafes. The feeling among media outlets, I suspect, was that to label Palestinian violence as ‘terrorism’ but not to use that word for the Israeli violence carried out by the IDF was unfair and perhaps biased. So there was a tendency to avoid use of the ‘t-word’ in the interests of balance.

This practice has delivered exactly the “constant misunderstanding” that Laqueur warns of. The inability of so many to distinguish between an IDF military strike on an armed Hamas base and the Palestinian terrorist carrying out an explosion on a civilian bus is surely related to the fact the media fail to make a distinction between the two acts of deadly violence.

The reason why it is important that the media do use the word terrorist, when it is appropriate, is that the public need to be informed accurately. The equivalance drawn between the terrorism and regular military violence obviously blurs the line and can lead, in the end, to a gradual legitimisation of terrorism as a tactic.