This is a guest post by Eyal

Winston Churchill famously once said that “America can always be counted on to do the right thing after it has exhausted all other possibilities.” To paraphrase, Benjamin Netanyahu finally formed the government that everyone knew that he would form the day following the elections, after he exhausted all other possibilities.

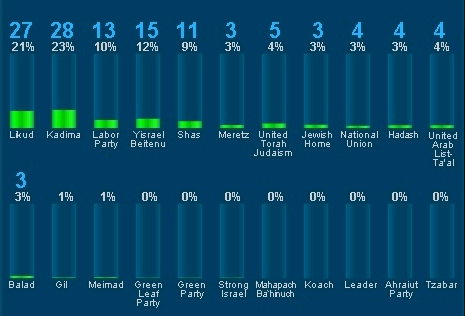

Finally, a government. After being granted the task, a Prime Minister has six weeks to form a coalition. On Saturday night, at the last possible moment, Netanyahu notified President Shimon Peres that he has formed a coalition, comprising of Likud, and the parties of Avigdor Lieberman (who’s party is in alliance with Likud), Yair Lapid, Naftali Bennett, and Tzipi Livni, for a total of 68 seats (out of 120). The government will be sworn in late Monday or Tuesday, just in time for Obama’s visit on Wednesday.

A rather small feat. Immediately following elections, I wrote a post on these pages predicting that Bennett and Lapid will form the basis of the coalition, along with Labour and Kadima, to form a left-right balance within the government with Netanyahu at the pivot. Labour decided not to join the government (a correct decision on their part, I believe) and Kadima got left out at the last minute, but instead Netanyahu brought in the dovish Tzipi Livni. So I wasn’t very far off. But admittedly this was a rather small feat on my part. Everyone knew that such would be, more-or-less, the structure of the government: Netanyahu, Lieberman, Lapid and Bennett forming its base, a dove to balance the right, and the ultra-orthodox on the outside. Everyone, apparently, except Netanyahu.

Everybody’s a winner. Surprisingly for such drawn-out and bad blooded negotiations, each of the coalition partners can boast some major achievements to their side. Lapid was able to exclude the religious parties, agree on a roadmap for drafting religious students, a reduction in cabinet size, and got responsibility for the treasury and education ministries (amongst others). Bennett was able to avoid being left out (due to Netanyahu’s animosity towards him), and was given (amongst others) the ministries of commerce, housing, and religious services, as well as the Knesset’s budget committee. Even Netanyahu, despite being strong-armed into forming a coalition he did not desire and leaving his “natural partners” out of it, got to retain the PM’s seat, the Foreign Office, Defense Ministry, Interior Ministry, Homeland Security, and to have an overall majority in the cabinet and other governmental forums, despite having an equal number of Knesset seats (31) as the Lapid/Bennett alliance. Netanyahu’s life is far from perfect, but given the circumstances this is quite an achievement.

A tale of two governments. There are, essentially, two governments in the present coalition. The first is the domestic government, led by Yair Lapid and Naftali Bennett. Between the two of them, they control the Treasury and the ministries of Housing Development, Education, Welfare, Health Service, Commerce and Knesset Budget Committee. The Likud, on the other hand, controls almost everything having to do with security/international relations, including the ministries of Defense, Foreign Affairs, Homeland Security, and the Knesset Int’l Relations & Defense Committee. It’s a bit early to tell how these two “governments” will co-exist, but it’s going to be interesting.

Possibly the most right-wing government. Ever. Make no mistake: despite the inclusion of the dovish Tzipi Livni and the centrist Lapid (who has a number of strong lefties in his party, as well), this is a very right-wing government – quite possibly the most right-wing government to have ever been formed. Apart from Netanyahu at the helm, Avigdor Lieberman will remain in-charge of the Foreign Office, Ze’ev Elkin – the previous Coalition Leader and a hard-right settler – will be acting Foreign Minister (while Lieberman himself is facing corruption charges), the hard-right Moshe Ye’elon will be appointed Defense Minister (bearing overall responsibility for the West Bank), Danny Danon, from Likud’s right-flank will be his deputy, Uri Ariel (a religious settler from Naftali Bennett’s party) will be Housing Minister (responsible, amongst others, for housing projects in settlements), and Bennett himself will be Commerce Minister, with special powers for expanding industrial zones in settlements. These are all figures unlikely to oppose settlement expansion and who will likely exercise their respective powers to advance building in the settlements as much as they can.

The Lapid Conundrum. Supposedly, Yair Lapid is the biggest winner so far. He came out of nowhere, became leader of the second-largest party (with just a single seat less than Netanyahu’s Likud), and forced Netanyahu to leave the ultra-orthodox out of government and accept most of his policies. Nonetheless, I am going to stand on a limb and say that Lapid’s position in the new government is the most precarious, because now he’s locked-in. For one, Lapid has very little leverage to oppose far-reaching right-wing policies because most of the rest of the coalition will support them. For Naftali Bennett, who aligned himself with Lapid during negotiations, this is a feature, not a bug. Moreover, if Lapid were to threaten to break away from the coalition over such measures, then Bennett certainly wouldn’t follow him and the ultra-orthodox parties will only be too eager to replace Lapid.

The basic question. For years, the center/left in Israel tried to advance the peace process at the cost of domestic concessions to the ultra-orthodox parties. Among others, this has allowed the orthodox to receive exemptions from military service and receive public funds far beyond their proportion in the population. For better or worse, now Lapid is doing the reverse: advancing domestic policies opposed by the ultra-orthodox at the cost of accepting right-wing domination of the security/peace axis. Whether or not this bargain will turn out better is the question that will define this government.