This is a cross post from The Times of Israel by Benjamin Kerstein

During the time I was a student in Beersheba, I lived in one of Israel’s poorest neighborhoods. I was at best a tourist in a country of poverty, but I was nonetheless struck both by the quiet dignity of its residents and by the near-complete lack of interest in their situation on the part of outsiders. Most of the aid that came their way was from religious organizations, primarily those affiliated with Shas, which despite its controversial image has probably done more for the poor than any other group in Israeli society today. There was, however, a youth center nearby, and one of the counselors lived almost next door to me. “Every life you save,” he once told me, “is a blessing.” From anyone else, it would have been a maudlin banality. From him, it was statement of defiance. So many of those lives had, after all, already been written off.

When I later moved to Jerusalem, the center of the world’s organized Jewish life, I could not help but be struck by a singular incongruence: The city was literally awash in Jewish organizations of every conceivable kind — liberal, conservative, religious, Zionist, etc. — all ostensibly dedicated to the welfare and well-being of the Jewish people. The money seemed to flow, at times, like water. I can well remember standing in Aish HaTorah’s new headquarters across from the Western Wall and wondering how many millions must have been spent on what was perhaps the second most coveted piece of real estate in the Jewish world.

And yet, the people of Beersheba might never have existed. The primary beneficiaries of the various organizations I encountered were almost exclusively members of the Jewish middle or upper classes, often from the Diaspora.

When one looks overseas, the picture is largely the same. The current obsession is Jewish continuity, for which I understand the current buzzword is “peoplehood.” This continuity, it is believed, will hopefully be ensured through a dazzling constellation of organizations and programs dedicated to Jewish youth, the overwhelming number of whom, once again, appear to be economically comfortable, if not prosperous. Indeed, there often seems to be a conviction on the part of the Jewish world that its poor — especially in Israel — do not exist. Or if they do exist, they are a marginal phenomenon, unworthy of much attention.

The causes of continuity, or outreach, or peoplehood, or whatever the issue of the moment may be, are quite worthy ones. But their dominating position on the Jewish list of priorities presents us with a rather disturbing conundrum: Millions, perhaps billions, of dollars are being directed toward people who do not need it. Lives are being saved — in other words — that are not in need of saving, and lives are being lost that need not be lost.

To an extent, this is a self-made problem. Jews around the world are naturally proud of Israel’s economic successes, and they make an excellent talking point when arguing with Zionism’s detractors — as should be evidenced by the violent overreaction those detractors recently directed toward Mitt Romney. But the truth is that the macroeconomic numbers conceal what is for many of Israel’s citizens a microeconomic crisis. There is the Tel Aviv that is admired even by the New York Times, but there is also Beersheba, Dimona, Umm al-Fahm, Kiryat Gat, and a hundred other towns that cannot begin to dream of such prosperity. All may rejoice that Israel is becoming another Hong Kong, but they must also reckon with the terrible question of what to do with another Kowloon. As the recent social justice protests have shown — and a terrible series of self-immolations have asserted with horrifying force — Israel’s prosperity is highly selective, and as the institutions that might ameliorate this have been starved by the headlong rush toward a high-tech-fueled neoliberalism, the painful contradiction between Israel’s prosperous minority and its struggling majority has become harder and harder to ignore.

Yet the organized Jewish world, particularly in the realm of philanthropy, has largely ignored it. Certainly, there are organizations doing yeoman’s work battling Israeli poverty (both Jewish and, lest we forget, non-Jewish), but they are dwarfed by those whose concentration is the spiritual well-being of the comfortable, and not the material well-being of the poor.

A homeless man sleeps on the street outside of a McDonald’s restaurant in Jerusalem (photo credit: Nati Shohat/Flash90)

A homeless man sleeps on the street outside of a McDonald’s restaurant in Jerusalem (photo credit: Nati Shohat/Flash90)

But to paraphrase Bertholt Brecht: First feed the face, then talk to me about peoplehood. If millions of dollars can be found to send a few hundred young middle- and upper-class Jews to Israel for a week, one imagines that many more millions might be found to improve the lives of thousands of young and not-so-young Israelis. To see much of the money, time, and effort that is now being expended on such projects as Birthright Israel redirected toward Israel’s poor — and the poor of the Diaspora as well — would be a welcome sign that reality is finally reasserting itself.

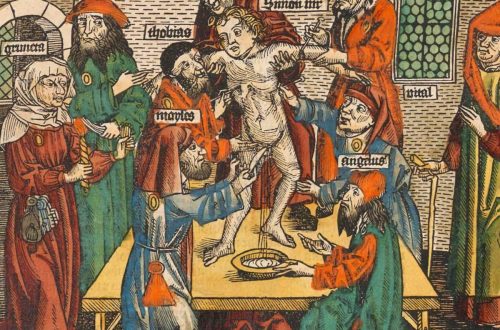

At the moment, however, the organized Jewish world’s priorities are so upside-down as to be incomprehensible and indefensible. There can be no meaningful peoplehood if part of the people lives in comfort and even wealth while another lives in poverty and even desperation. Thousands of years ago, one of our ancestors invoked the holy name to denounce those who “built the high places… to cause their sons and their daughters to pass through the fire of Moloch.” Our sin is hardly as great as that, but we have built our high places, while others pass through the fire. It does not have to be this way; and it would not, in fact, be difficult to change. One hopes that we will choose to do so.