I know many Harry’s Place commenters have reacted angrily to The New York Times’s coverage of the Iranian protests.

But as the uprising continues into its second week, and as the regime tries to crack down by arresting and attacking protesters and cutting off their means of communication, I found a recent Times piece by Amir Ahmadi Arian on the outbreak of rage on the streets of Iran informative and credible.

Arian starts by noting the differences between the current revolt and the protests that followed the rigged presidential election in 2009.

So far, the middle class and the highly educated have been more witnesses than participants. Nonviolence is not a sacred principle. The protests first intensified in small religious towns all over the country, where the government used to take its support for granted. Metropolitan areas have so far lagged behind.

Demands like freedom of speech and the rights of women and religious minorities have, for the most part, been either absent or vaguely implied. In one of the rare videos of protesters talking to the news media, they all mention unemployment, inflation and the looting of national wealth: A woman asks President Hassan Rouhani to live on only her salary of $300 a month; a veteran of the Iran-Iraq war says he considers himself among “the forgotten”; an elderly woman talks about her 75-year-old husband, who works long hours to make ends meet. The chants are also different this time. “Where is my vote?” and “Free political prisoners!” dominated in 2009. Today they have been replaced with “No to inflation!” and “Down with embezzlers!” and “Leave the country alone, mullahs.”

In fact the middle class, which was the driving force in the 2009 protests, has largely been absent, and even contemptuous.

Protests over economic grievances are hardly new in Iran: riots over inflation in Islamshahr and Mashad in the 1990s, frequent strikes by the bus drivers union in the 2000s, protests by schoolteachers over unpaid wages. Those voices were barely heard. They came from the bottom of society and were either stifled halfway through by the government or drowned out by civil rights activists with better access to the international media. They have now forced their way to the surface and emerged as a resonant, nationwide cry for justice and equality.

In recent years there has been a steady stream of under-reported news coming out of Iran about labor unrest, strikes and jailed union leaders. Harry’s Place began reporting more than a decade ago about the brave leader of the Tehran bus workers’ union, Mansour Osanloo, who was imprisoned by the regime and ultimately forced to flee the country.

Since the 1979 revolution, Iranian politics has been defined by a split between reformists and principlists, conservatives who say they are devoted to the principles of the revolution. During the 1999 and 2009 uprisings, the protesters enjoyed support from powerful reformists. This time, the dichotomy has been transcended. The demonstrators don’t want support from anyone associated with the status quo, including Mr. Rouhani, the reformist president. No wonder prominent reformist figures, even Ebrahim Nabavi, a dissident journalist living in exile, disparaged the protesters as “the potato-eating mob.”

Arian notes the anger among poor and working-class Iranians at the conspicuous displays of wealth by the Iranian elite, who seem willing to tolerate the Islamic regime as long as they can keep their privileges and do what they want outside the country or behind closed doors.

Wealthy young Iranians act like a new aristocratic class unaware of the sources of their wealth. They brazenly drive Porsches and Maseratis through the streets of Tehran before the eyes of the poor and post about their wealth on Instagram. The photos travel across apps and social media and enrage the hardworking people in other cities. Iranians see pictures of the family members of the authorities drinking and hanging out on beaches around the world, while their daughters are arrested over a fallen head scarf and their sons are jailed for buying alcohol. The double standard has cultivated an enormous public humiliation.

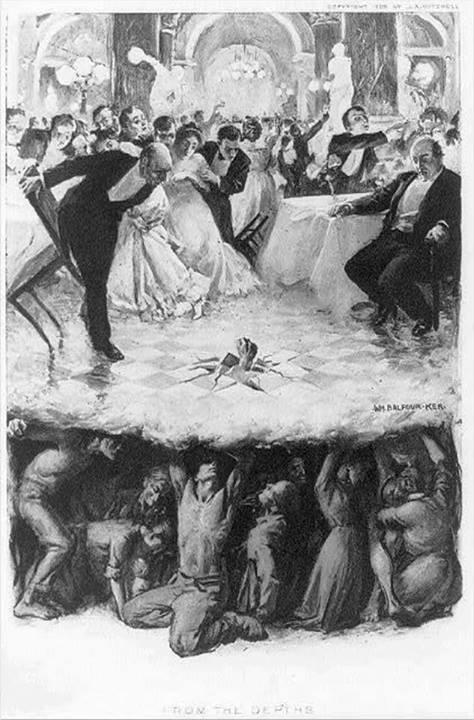

What’s happening now may be an updated Iranian version of “From the Depths,” a 1905 drawing by the socialist artist William Balfour Ker— which makes it all the more ironic that so many “leftists” are ignoring or downplaying these events.

Although the regime may succeed in crushing the current uprising, Arian writes:

[S]omething has fundamentally changed: The unquestioning support of the rural people they relied on against the discontent of the metropolitan elite is no more.