Those interested in, or masochistic enough to read, my ramblings will know that I sometimes look back to see if there are any lessons.

One thing that struck me is how “modern” politics has been dominated by a succession of figures who had about a decade at the top, although not necessarily all as Prime Minister.

I see “modern” politics starting in the early 1960s when WW2 was a decade and a half away, Churchill retired as Prime Minister in 1955, in late 1956 the Suez Crisis showed that Britain wasn’t a Great Power any more, and the Wind of Change speech was made in early 1960.

Rock and roll was all the rage (Cliff Richard had his first hit in 1958 and the Beatles burst onto the scene in late 1962), the Lady Chatterley’s Lover trial was in 1960, the same year as the Pill started UK trials.

The political landscape was also changing. As recently as June 1953 Churchill suffered a stroke which was kept from all but a few, but in the early 1960s politicians were taken off their pedestals in the satire boom. Beyond the Fringe premiered in 1960, The Establishment club opened in 1961 and That Was The Week That Was started in November 1962.

In February 1963 the Grammar school educated, media friendly Harold Wilson became Leader of the Opposition. He was twenty two years younger than Harold Macmillan who went eight months later.

This paralleled the US where Kennedy, a little over a year younger than Wilson, had become President two years earlier, replacing the twenty seven years older Eisenhower.

There had been a generational shift on both sides of the Atlantic, and by July 1965 the Conservatives had their own “Grammar school boy”, Edward Heath, only four months younger than Wilson.

They would contest four elections. Wilson won in 1966 and October 1974. Heath won in 1970, whilst February 1974 was a win on points for Wilson; Heath got most votes although Wilson won most seats and formed a minority government.

Heath was ousted in February 1975 and Wilson quit in June 1976, the decade of back and forth between them is unlikely to be repeated.

The next dominant figure, Margaret Thatcher, was waiting in the wings and would win a hat trick of elections in 1979, 1983 and 1987 before quitting in 1990.

Unusually the next long-server, Tony Blair, wouldn’t become Leader of the Opposition for more than three and a half years and it would be almost six and half years after Thatcher’s departure before he won his first election in 1997.

After his third victory in 2005 Blair advised that he didn’t intend to fight another election and was replaced by Brown two years later.

David Cameron, however, had been on the front row of the grid since December 2005, working to make the Conservatives electable. He would form a coalition in 2010, which he would convert into a majority in 2015 before quitting after the 2016 EU Referendum.

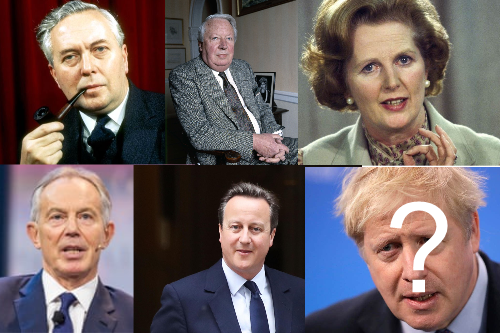

The era of “modern” politics has had the following long-serving dominant figures:

Wilson/Heath – mid 1960s to mid 1970s.

Thatcher – late 1970s to late 1980s.

Blair – mid 1990s to mid 2000s.

Cameron – mid 2000s to mid 2010s.

Nothing was inevitable.

Wilson only became Leader of the Labour Party due to the unexpected death of Gaitskell.

What would have happened had Callaghan called an October 1978 election?

Blair became Leader of the Labour Party following the premature death of Smith, who’d laid the foundations for New Labour, and, with the Major government in trouble, was clearly setting the agenda in the run up to 1997. It can be argued that Blair’s ascent caused Major to become Mr Micawber and hang on as long as possible.

There was talk of Brown calling an election in Autumn 2007, which would, in hindsight, have been before the financial crash.

It’s now three and a half years since Cameron’s departure and, if history does repeat itself, we should be looking for the next person to dominate the scene for about a decade.

There have, of course, been false dawns.

When the 2016 Conservative leadership contest collapsed leaving Theresa May as winner by default the omens were initially good. Simply surviving as Home Secretary for six years indicated competence and she was clearly decent and diligent, although somewhat staid.

Another Labour leadership contest distracted the opposition and in early 2017 the Conservatives gained a seat in Copeland, not what governments are supposed to do!

When May called a general election in April 2017 many lefties thought it was all over and some Corbynsceptics saw no chance of government before 2025, at the earliest. The dementia tax, Maybot, “nothing has changed” and fox hunting, up against a better than expected Corbyn and a freebie-packed Labour manifesto, changed a predicted landslide into a hung parliament and May into a dead woman walking.

In the aftermath Corbyn predicted that he would be Prime Minister within six months but the Conservatives remembered “absent friends” and dug in.

Corbyn’s history and worldview then started to become important as May’s agreement with the DUP was partly based on keeping an IRA supporter out of No. 10.

Salisbury, Syria, wreathgate and antisemitism showed his unfailing ability to back the wrong side and 2017’s benefit of the doubt disappeared to the extent that even with all May’s problems Corbyn was third in a two horse race (trailing don’t know!).

Entropy had set in before the election campaign and “one more heave” failed miserably against Johnson and a Conservative Party that had learnt from 2017.

Johnson has now secured the best Conservative result since the 1980s. Could he be the next to dominate politics for a decade?