This is a cross-post by Kyle Orton

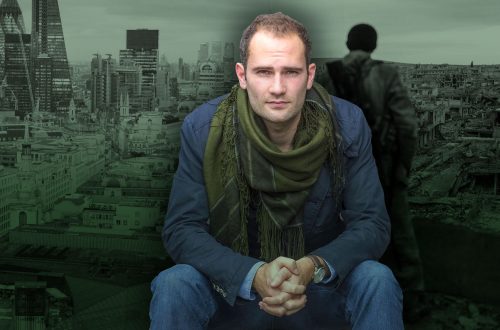

Abdul Hadi Arwani

Abdul Hadi Arwani, a Syrian-born imam, was found shot dead in his car on Tuesday in Wembley, northwest London. The British police are still refusing to officially name Arwani, but his friends and supporters have done so. Arwani leaves behind six children.

There are many possibilities for who killed Arwani. As the manager of a construction firm, it could be a deal gone wrong. The involvement of anti-terrorism police in the investigation into Arwani’s murder could indicate a far-Right anti-Muslim assailant. However, a source close to the investigation said that Arwani was struck down in an operation that had all the hallmarks of a “State-sponsored assassination“. To find that the long arm of Bashar al-Assad’s mukhabarat had caught up with Arwani would hardly be a surprise.

Arwani, who has been an outspoken opponent of the Assad family dictatorship for several decades, has been involved in anti-Assad activism since the uprising began in 2011. Arwani wasinvolved in an anti-regime demonstration at the Syrian Embassy in London in March 2012 that turned violent, and was associated with the Syrian political opposition, the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces (ETILAF). Arwani has also spoken out against the Islamic State (ISIS).

Arwani was born in Hama City he said, and escaped that city as a sixteen-year-old in 1982 after the revolt against Hafez al-Assad was crushed there. Arwani went to Jordan and studied at the Faculty of Shari’a, before arriving in Britain in 1995, teaching Islamic Studies and matters of the Holy Law in Slough and West London.

Between 2005 and 2011, Arwani was the imam at an-Noor Mosque in Acton, west London. It has been reported that Arwani was forced to resign over accusations of extremism; others saythe dispute was financial. Whatever the truth of this specific question, an-Noor is a well-known platform for Islamic extremists. One of an-Noor’s directors is the pro-HAMAS Daud Abdullah, former Deputy Director General of the Muslim Council of Britain.

An-Noor was the scene of an embarrassing cock-up when the security services lost track ofMohammed Ahmed Mohamed, a Somalia-born terrorist connected to al-Qaeda’s Somali branch al-Shabab, which has extensive networks in London, of which Mohammed Emwazi a.k.a. “Jihadi John,” ISIS’ British video-beheader, was at one point a member (see here, here, and here.) Mohamed’s current location is unknown.

An-Noor Mosque also produced Ali Almanasfi, a Brit who went to Syria and was at leastaffiliated with Ahrar a-Sham, the most powerful Syrian insurgent unit, whose leadership is nonetheless ideologically hardline with links to al-Qaeda. Ahrar fights in close military alliance with Jabhat an-Nusra, al-Qaeda’s Syrian branch. Almanasfi was reported killed in May 2013; this has been disputed.

Arwani personally was pictured with Raed Salah at an-Noor Mosque. Salah, an Israeli Arab, wasimprisoned for raising millions of dollars for HAMAS and having contact with an Iranian intelligence agent, and was re-imprisoned for assaulting a police officer. Arwani was also part of an event for Ramadan last June that was jointly hosted by the London Muslim Centre (LMC) and the Islamic Forum of Europe (IFE).

LMC is part of the East London Mosque, one of the most infamous promoters of Islamic extremism in Britain—it hosted Anwar al-Awlaki in 2009, for example. The East London Mosque as a whole is functionally under the control of the IFE. IFE opposes democracy, supports Muslim theocracy, and is closely tied to Jamaat-e-Islami, which was complicit in the 1971 massacres (that some say amount to genocide) against the Bengali population of what is now Bangladesh, then East Pakistan.

Arwani’s personal beliefs, while clearly Islamist, will be a matter of interpretation. In 2012, Arwani built his case against the Assad regime based largely on its repression and corruption, spoke in support of the Free Syrian Army and protecting the minorities, and even spoke favourably about the protection afforded citizens in the West. The speech, however, did include a paranoid assertion that Omar al-Bashir was under international indictment while Assad was not because of Israel’s interests, and Syria was framed as an Islamic struggle. Arwani called on his audience to send money to Syria because those fighting against Assad were “protecting the dignity of the umma“. In a speech in 2013, Arwani said, “the victory is coming for Islam,” and in the same year Arwani was on a talk-show discussing jinn.

A May 2014 speech by Arwani included overt sectarianism. “Syria … is a country of eighty percent of Muslim Sunnis. Forgive to say [sic] ‘Sunnis’. We have to use it because now lots of people are playing around with the definition of Muslims,” Arwani said. Arwani noted the 1964 uprising in Hama, which had erupted in response to the minority-domination and supposed secularism of the then-new Ba’ath regime. Arwani charged that the Assad regime had “impose[d] their kufr [disbelief] deliberately in front of the Muslims”.

Combing Arwani’s available speeches, his links to ETILAF, and being in Hama the first time around, it seems likely Arwani was associated with the Muslim Brotherhood, in ideology if not in organisation.

The most powerful objection to the idea that Assad killed Arwani is that Arwani “wasn’t a big fish“. But this is an argument that can be turned on its head. The Syrian opposition has already been demoralised by the West giving Assad an air force and extending him further legitimacy. An easy way to help the collapse of the opposition is to make clear that anybody who opposes the regime, however seemingly insignificant and even in a Western capital, risks assassination.

Another possibility, however outlandish, following from the logic of Arwani’s unimportance, is that Arwani was caught up in Assad’s efforts to discredit the rebellion through provocation. There are unconfirmed reports that Arwani “returned to Syria” last summer, and even that headdressed the East London Mosque remotely while there. It would be good to know what Arwani did while there and who he met.

Assad’s intelligence agencies were trained by the KGB, and Russia has been heavily involved as Assad uses provocation, a KGB-perfected tactic, in Syria, ensuring that the balance of power within the insurgency favours the extremists to discredit it locally and internationally, with hopes of drawing in international support to defeat the insurgency—something that has effectively now happened. Finding that this campaign had gone global—that Assad was working to make all the spokesmen for the revolution abroad extremists—would be no great surprise.

Given the Assad regime’s predicament, if the regime did this, then Iran and/or Russia are probably in the picture, too. State-sponsored terrorism in London from those quarters is no hypothetical. I wrote recently about Iran’s long record of terrorism in Paris, but Iran has carried out terrorism in London. Moscow was complicit in the 1978 assassination of Bulgarian dissident Georgi Markov in London—the infamous “Umbrella Murder”. In 2006, Alexander Litvinenko, a defector from the FSB (the successor to the KGB) was killed in London with a radioactive substance, almost certainly at the behest of Vladimir Putin’s regime.

Still, plenty of other options remain, some of them non-political. And even in the political realm, given that Arwani was anti-ISIS, the possibility that some freelancing Daesh sympathiser killed the imam cannot be ruled out. The tricky part is that, if Assad and his allies are involved, whatever the professed motive or identity of the killer turns out to be, it might transpire not to be quite as it seems.

Even more skilled than the Soviet Union at “black actions” was Jugoslavija’s UDBA, which has been plausibly accused of killing Jill Dando in London in 1999 and which certain did kill nearly one-hundred people, mostly Croatian opponents of Tito’s regime in Western Europe—some violent, some not—between the mid-1960s and late 1980s, including in Britain. The UDBA’s method of penetrating networks of opponents, sowing chaos, getting enemies to do self-destructively extreme things, and killing them in the confusion worked best precisely in cases where their victim had numerous enemies with a motive for murder.

The main outcome of Arwani’s killing, if the Assad regime—and thus Iran, to one degree of another—are responsible might well be a reminder that while Iran is a global terrorism threat in the here-and-now, as it has been for more than three decades, ISIS is at this stage mostly a regional threat, and thus proposals to align with Iran against ISIS perfectly miss the fact that Iran is by far the greater danger.