This is a cross-post from Jacobinism

PART ONE: ALL ARE GUILTY

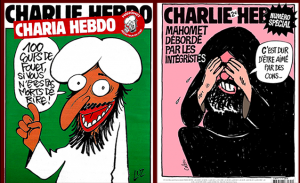

One of the most pernicious arguments advanced to persuade us that the murdered staff of Charlie Hebdo were unworthy martyrs to free expression – or were even deserving of much in the way of sympathy – has been the notion that they were the victimisers of a persecuted minority:

But the question needs to be asked: were the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo really satirists, if by satire is meant the deployment of humour, ridicule, sarcasm and irony in order to achieve moral reform? Well, when the issue came up of the Danish cartoons I observed that the test I apply to something to see whether it truly is satire derives from HL Mencken’s definition of good journalism: it should “afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted”. The trouble with a lot of so-called “satire” directed against religiously-motivated extremists is that it’s not clear who it’s afflicting, or who it’s comforting.

My objections to this argument, formulated here by the author Will Self in an article for Vice magazine, are great and numerous. For a start, I would have thought it self-evident than anyone who thinks it acceptable to answer cartoons by murdering cartoonists is in pressing need of moral reform, thereby invalidating Self’s objection by his own lights.

Furthermore, the job of the satirist is to scorn hypocrisy, double-standards, fallacious reasoning, and pomposity wherever it occurs and without political prejudice. That Self would prefer it if satire were a kind of comedy-activism, preferably mocking only those deserving of his own contempt, is beside the point. H. L. Mencken is of no use to Self here since (a) the quotation he cites is misattributed and originally intended to satirise journalistic moral vanity not endorse it, (b) journalism is not the same as satire, and (c) in any case, journalism ought to concern itself with the pursuit of truth, not the affliction of comfort.

But most important of all, in the service of an argument designed to transform victimisers into victims and vice versa, Self misrepresents the motives of the assassins. It was not the mockery of religious extremists to which they objected, but the disrespect shown to a religious figure they venerated. “We have avenged the prophet!” they cried as they fled the scene of a bloodbath they had committed in his name.

|

|

| Will Self |

Muhammad, Islam’s purported seer, claimed to be the vessel of the final and perfect word of god, and he is consequently considered to be a figure of considerable power and authority by Islam’s ~1.5 billion Muslims. (He has also been dead for nearly 1400 years, which is about as comfortable as it is possible to get.)

Were Islam a quietist faith, whose adherents wanted nothing more than to be able to retreat from the fallen world, Self’s argument that its absurdities are the business of no-one but its adherents might be more persuasive. But Islam is proselytising faith, and in its radical political form – also known as Islamism – it constitutes an aggressive ideology which is expansionist, totalitarian, and revolutionary in character, as well as being both triumphalist and (paradoxically) self-pitying.

Saïd and Chérif Kouachi, the assassins of Charlie Hebdo’s journalists, are said to have been the cadres of Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, and as such would have held extremely definite and retrogressive views about the ways in which, not just journalists, but also women, gays, and non-believers of all stripes are required to behave, and all of which derive from a literalist interpretation of Muhammad’s own ostensibly inerrant utterances.

In the Shi’ite theocracy of Iran, the Sunni monarchies of the Gulf, and the nascent Caliphate in Iraq and Syria, radical Islam enjoys the privilege of State power and its cruelty and retrogressive effects on individual rights and liberty are manifest. But in the West’s liberal democracies, radical Islam is (mostly) the province of immigrant minorities from North Africa and the Asian sub-continent. An analysis that goes no further than identifying the underdog will spare its ideology scrutiny and ridicule, and insist that it be treated with the deferential respect its adherents demand. Even, apparently, as religious proscriptions are enforced at the point of a blazing kalashnikov.

Those for whom power imbalance is the only prism through which to understand the moral calculus in a given conflict make two mistakes. The first is to place scant significance on what either side is actually fighting for – if one’s person’s terrorist really is another’s freedom-fighter then it makes no difference whether democrats are fighting to overthrow totalitarian State or totalitarians are fighting to destroy a democratic one. The second mistake is a failure to appreciate the coercive power of the weak: the use of arbitrary violence to intimidate, destabilise, and terrify.

To Self such objections appear to be of negligible importance, and he scorns the assistance Charlie Hebdo accepted from the French government in the aftermath of the violent catastrophe visited upon them, as if this tarnishes a claim to ideological purity to which he has already made it clear the magazine is not entitled: “[S]o, now the satirists have been co-opted by the state, precisely the institution you might’ve thought they should never cease from attacking.”

He chides the journalists of Charlie Hebdo for their lack of responsibility, secure as he is in the knowledge that his own sensitivity to the plight of the weak means he will never have to answer to their vengeful hatreds. This strikes me as not just conceited, but also foolish. It is not beyond the realms of possibility that some capricious jihadi might take it upon themselves to demand the suppression of a Will Self novel because it violates this or that medieval edict, and it is not hard to imagine the high dudgeon that would immediately result.

And let it not be overlooked that four Jews were also murdered by the Kouachi brothers’ co-conspirator for no other reason than that they happened to be Jews; a reminder that Islamism’s murderous rage is by no means confined to those who denigrate the faith. In 2006, Self publicly renounced his Jewish heritage – an ostentatious display of disgust occasioned by some Israeli policy or other that failed to meet with his approval. I’m dubious as to whether this will inoculate him against Islamist anti-Semitism, should he ever find himself at its mercy.

Self is a man whose languid verbosity tends to be taken for wisdom by the unwary. It would be silly to deny the man’s talents as writer, but they prop up childish political instincts. His tutorial on the limits of free speech is followed by the news that he won’t be conscripted into a defence of “the Enlightenment project”. His objection is of the “who-are-the-real-monsters-anyway” variety.

The reasons that a revolution built upon the Declaration of the Rights of Man spiralled into the gory despotic excesses of the Red Terror are complex and fascinating, but for Self they illuminate nothing more than the unfitness of the Enlightenment’s inheritors and “boosters” to pass judgement on anyone but themselves. Like the religious fanatics they denounce, the West’s fundamentalists of reason are in pursuit of a chimeric utopia “that if it’s perfected it will render the entire population supremely free and entirely good.”

No source is provided for this ventriloquised hyperbole because, as far as I’m aware, none exists within the realm of sane commentary. Not content to have damned the Enlightenment’s messy inception, Self proceeds to deride its progressive legacy:

[S]uch rarefied progress is precisely what is mocked, not only by the murdering of Parisian journalists, but by the drone strikes in Syria, Iraq and Waziristan, which are also murders conducted for religio-political ends. It is mocked as well by the clamouring that follows every terrorist outrage for the suspension of precisely those aspects of the law that exist to restrain our worst impulses; in particular the worst impulses of our rulers: namely, due process of law, fair trials, habeas corpus and freedom from state-mandated torture and extra-judicial killing.

Self opens his article by announcing he wishes to be clear, before demonstrating a thoroughgoing contempt for moral clarity. He describes the premeditated murder of journalists for perceived lapses in taste and propriety as “evil”, but with his casual ruminations on responsibility and the nature of satire, he floats the notion – without having the courage to actually defend it – that the murdered journalists and cartoonists were partly culpable in their own deaths.

And he is at pains to remind us that, while we share the Kouachis’ capacity for evil, in our moral complacency we may have exceeded it. Terrorists pursue their delusory utopia at our expense using automatic weapons, while we pursue ours at theirs using drone warfare. In Self’s mind, Islamist barbarism convicts us all, its chauvinism and cruelty simply reflects our own. All are guilty, so none are guilty; an exoneration of terrorism by default.

Not only does such lamentable moral equivalence fail to distinguish between the firefighter and the fire but, at a time when much of the Middle East, North Africa, and Pakistan are being torn to pieces by religious fanaticism, are the civilisational benefits of universalism, rationalism, and self-criticism really so difficult to discern?

It would be nice if beneath all this contempt there lay some sort of coherent moral argument. Alas, all I can find is the perverse vanity of radical self-disgust. For if the pitiless Deobandi fanatics of the TTP wish to subjugate Pakistan’s Swat valley, or if the demonic Takfiri lunatics of the Islamic State wish to enslave Yazidis, crucify Christians, and massacre Kurds, then what right have we to object, still less assist those resisting such violence, when we are burdened with the legacy of Robespierre, Danton, and Saint-Just?

As Christopher Hitchens remarked when he found himself confronted by an argument of comparable masochism at the 2007 Freedom from Religion Foundation:

Well, there you have it ladies and gentlemen. You see how far the termites have spread and how long and well they have dined. When someone can get up and say that in a meeting of unbelievers – that the problem is Western civilisation not the Islamic threat to it – that’s how far the termites have got.

Do read the rest of Jamie’s post here