This is a guest post by Iram Ramzan

Writer and Journalist Yasmin Alibhai-Brown is not one for avoiding controversy. Her latest book, ‘Refusing the Veil’, will no doubt be criticised by many Muslims and those on the left – Myriam Cerrah recently wrote a scathing critique for the New Statesman.

While I am broadly with YAB on the niqab, there are some issues that I found troubling in her book, and Cerrah’s subsequent critique.

Whatever the reasons given by women for wearing the face veil, we cannot deny that it was initially prescribed in ancient times by men to women as a sign of their subservience. It is a barrier and physical separation intended to keep women in their place.

YAB has a point when she asks, “Why is market-driven brainwashing scandalous, but brainwashing perpetrated through religious dogma perfectly respectable?” Quite. We should be able to criticise ideas, regardless of where they are taught. An idea should not be not be off limits simply because it is in a religious book.

I regularly see young girls wearing headscarves, which YAB criticises in her book, but unfortunately this is nothing new. Whether it is in the form of hijabs, not being able to partake in swimming lessons, or unable to wear Western clothes, girls have always been controlled by their families and had many restrictions placed upon them. It is just now, in this climate, we are noticing this more.

Although I broadly agree with YAB’s views on the niqab, my problem is that on the one hand she claims women are veiled because they are seen as sexual objects and their sexuality is dangerous to men, then denounces women for showing flesh as being sexual objects too.

On the BBC Asian Network [23:50], she said she would be upset if she were a Muslim man who was seeing all these girls being covered up as though they are somehow in “danger”.

But then she goes on to contradict herself, when she discusses “half-naked lasses” in a rather patronising manner.

One sees young women in clothes that call out to men. Preteens, younger girls, sometimes toddlers are dressed in flirty, foxy gear… These come-hither styles benefit only men and big business… Why are we allowed to question and criticise women in tarty clothes, but not hijabis.

If a man is turned on by a toddler in “foxy gear” then that is his sick problem. YAB criticises women for showing flesh in the same ways that more orthodox Muslims would denounce her for not covering her hair. She uses the same language that rape apologists use against women. Her words to describe the west as “materialistic, hedonistic, socially anarchic, sex-obsessed and atomised” could have been used by an Islamist.

There is a hierarchy when it comes to clothing with some Muslims. Those who wear niqabs and hijabs are at the top of the food chain, then the likes of YAB are somewhere in the middle and those wear “tarty” clothes are right at the bottom, loathed equally by Islamists and YAB alike.

YAB compares niqab to a micro miniskirt. Correct me if I’m wrong, but as far as I am aware no woman has been whipped or had acid thrown on her face for not wearing a miniskirt, or refusing to wear a bikini. The comparison between the two is false.

Where do we draw the line between what amount of flesh is deemed ‘appropriate’ and ‘tarty’?

Salafisation?

YAB comes from a middle class background where Muslims she knew were very secular and largely unobservant. She discusses at great length the more tolerant versions of Islam that were followed by her and her friends. I am glad that she did not have an austere upbringing like some have had.

But she, and Cerrah, need to come to my part of the UK. Here, Muslims, largely of south Asian origin, have always been more conservative and religious. When I went to school I would see young Pakistani girls take off their headscarves as soon as they came to school and put them back on again before they had to go home. These were the same girls who, as soon as they completed their GCSEs – and subsequently failed because their parents put no emphasis on their education – would be married off to a cousin in Pakistan.

YAB claims Bangladeshi women in East London never covered up. But again, where I live, the only women while I was growing up who did wear the niqab were the older Bangaldeshi women. Yes, we see more niqabs in many communities now, but to argue that women have suddenly gone from being covered to hiding behind niqabs is simply not true.

This romanticisation of history, as though life in the previous generation was better, really needs to stop. YAB forgets that the earlier immigrants were subjected to overt racism, brown girls were taken out of schools and forcibly married off to older men they did not know, female education was not seen as a priority, and girls were often not allowed to wear western clothes. Life in the 60s and 70s was not glorious for immigrants or their children.

Many female, Muslim activists I know are worried about the growing trend of what they see as Salafisation of Islam. While I agree with them to an extent, it could be argued that globalisation and not just Saudi funding has made big hijabs and fancy abayas now attractive to wear, as well as sometimes being more practical for Muslim women who do not want to wear a pair of salwar kameez. It may not necessarily be something they deem as more ‘Islamic’ – though many do – but something that is trendy.

Who knows what trends we will see in the next generation? Perhaps a different version of Islam will be seen as the norm, rather than this austere form being propagated by Saudi petro-dollars. My theory is also that Muslims will become more polarised. While some turn to extreme versions of the faith, many more will turn away from it altogether.

The ‘usurpation of liberal feminism’?

Although I do not agree completely with YAB, I do not agree with Myriam Francois Cerrah’s critique of her book. The Oxford University-based writer and academic criticises YAB for not analysing other religious garments, but the book is specifically on the veil. What part of that did she not understand? In YAB’s defence, she did say on Asian Network that she has a problem with young Sikh boys being made to cover their hair too.

As for vitamin D deficiency in women who wear veils, Cerrah responds in Marie Antoinette style – let them take supplements instead.

If YAB has a middle-class bias, then Cerrah’s voice can be aligned with reactionaries and Islamists who will no doubt use her articles to attack any dissenting voices. She attacks YAB for being monolithic despite the fact that she herself attacks anyone who does not conform to the majority.

The title of Cerrah’s piece is “The feminist case for the veil“, yet I could not spot a single case for it, just a lot of anti-colonial sentiments wrapped up in academic terminology. Meredith Tax wrote a good piece in which she analyses this sinister rhetoric used by the likes of Cerrah.

She then accuses YAB of pandering to the far-right, which is really unfair as they loathe YAB just as much as the Islamists do. This is the same woman who once described ex-Muslims as “native informants”.

As blogger John Sargeant succinctly put it, “Yasmin is accused, in the most scholarly way of avoiding the word, of being a coconut… Myriam Francois-Cerrah has written a masterpiece in how to usurp liberal feminism in the cause of reactionary orthodoxism.”

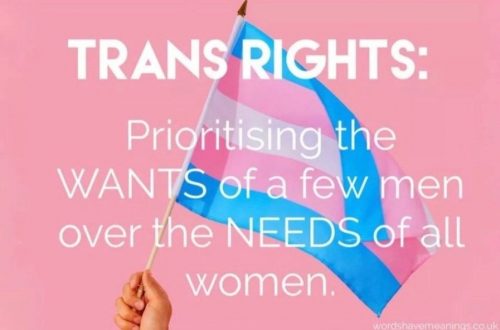

Cerrah does not like the idea of the state telling women how they must dress but fails to point out the elephant in the room, which is that her faith does. Choice is the key word here. A lot of Muslim women, we are told, choose to wear the hijab or niqab without any pressure from their families. That might be true.

But can it truly be a choice when women are told from day one that they are Islamically required (verse 24:31 in the Qur’an) to cover their entire body in the name of modesty? Women have been taught that a good Muslim woman must cover her hair and though a niqab is not mandatory, you are instantly seen as more pious if you do wear it.

It says it all when more Muslims will defend a woman’s right to wear a niqab or hijab but will not support or defend her right to remove it. It is not a choice if you cannot remove the hijab after you decide to wear it. A hijab is for life after all.