This is a cross-post by Shiraz Maher

The original defiance came without malice or forethought. A group of barely pubescent schoolchildren, buoyed by the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt, bought a can of spray paint. ‘The people want the downfall of the regime,’ they scrawled on the school wall, mimicking the popular slogan of protesters in North Africa. Syria’s already nervous Ba’ath administration would abide no dissent. The boys were arrested and disappeared.

Two years ago today protesters mobilised across the country in support of the missing children, marking the start of the Syrian uprising. It was too late. The boys had already perished. And when Assad’s forces opened fire on protesters, many others perished too.

The government crackdown only fuelled further dissent. Compounding this outrage was the near constant drip feed of footage on YouTube revealing a catalogue of truly unthinkable abuses. Hamza Ali al-Khateeb, a moonfaced 13 year old, was arrested at a protest in April. Days later his family received his corpse. No one needed ask what happened. Khateeb’s body was bruised, battered, and butchered – literally. His skin was torn, twisted, and shorn in a manner which would cause obvious suffering but not death. Cavities from bullet wounds replaced his kneecaps, offering a makeshift ashtray for Assad’s apparatchiks. Khateeb’s penis had been cut off. His father was then detained by state security and hours later appeared on state television wearing a stilted, rigor mortis smile. The deceit was complete when he thanked Bashar al-Assad for retrieving his son’s corpse after ‘terrorists’ had kidnapped him.

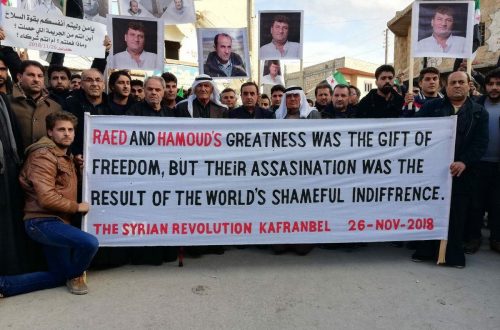

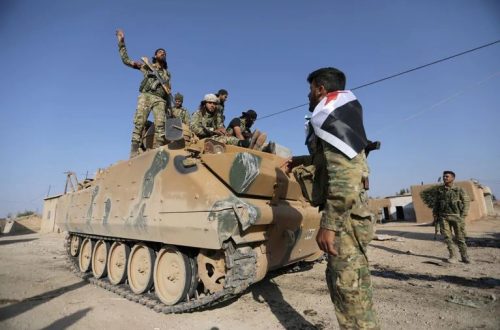

Khateeb remains one of the faces of the Syrian revolution in a war that could offer tens of thousands more. The Syrian conflict has, however, fallen victim to the jihadist synecdoche where this one part has comes to characterise the whole. Yes there are jihadists and Islamists fighting Assad, but the opposition is much broader than this.

Although the spectre of jihadist involvement in Syria is an alarming development, it should not overshadow the story of ordinary civilians on the ground. No one talks anymore of the original protesters who demonstrated peacefully under a volley of bullets. The many thousands of victims – male and female – who suffered terrible sexual violence in Syria’s prisons are largely forgotten. Little is written about the thousands orphaned by the conflict.

Two years into the revolution, this is where politicians need to focus their attention: alleviating the overwhelming humanitarian crisis engulfing ordinary people and destroying an entire nation. To contemplate the numbers is to gain an insight into the scale of the problem. In just 730 days around 70,000 people have died; 200,000 are missing or detained; 1.2 million are internally displaced; 1 million are refugees. The longer this conflict goes on, the more depressing those figures will become.