This is a cross post by Michael Weiss

Those who naively cling to the idea that a “peaceful” or “negotiated” transition is possible in Syria need only consider one of the points made by the late Marie Colvin in one of her last dispatches from Homs. (It’s a testament to the quality of war correspondence that her footnotes could be other people’s headlines.) Explaining that this besieged city had run out of Free Syrian Army targets to hit, Colvin told the BBC a day before she was killed that civilians were effectively trapped in an area being pounded with heavy artillery and rockets.

The International Red Cross has been trying for days to broker a ceasefire with the regime to allow badly needed humanitarian aid into Homs. So far, their efforts have come to nothing. What this means is that any pretence that Bashar al-Assad is trying to suppress an armed uprising now stands exposed as little more than the conceit of those too soft-hearted to accept the existence of true evil. He is terrorising for the sake of terrorising.

I’ve been arguing for months that another Balkans crisis, if not another Rwanda, was unfolding in Syria in slow motion. The sceptical response to this notion took several forms. Surely Assad wouldn’t dare commit mass atrocities – “another Hama” – broadcast on international news networks? Surely Twitter, Facebook and YouTube have altered the scope for Arab Spring repressions? But as Nick Cohen showed in You Can’t Read This Book, the internet hasn’t changed the nature of totalitarian dictatorship, which always seems to adapt its methods of repression just as quickly as new freedoms are discovered. And so: two Irish telecom companies have provided the Syrian intelligence “Branch 225” with technology to filter text messages, according to a recent report by Bloomberg. Elsewhere we’ve seen how the regime’s propaganda (“armed gangs,” “terrorists”) have been regurgitated by a slick English-speaking Kremlin “news” organ, or even echoed in the framing of early reports by Western outlets, which suggested massacres may have been quid pro quo for the shooting of security forces. (Now that Western journalists are on the ground to see what is happening for themselves, this narrative has changed dramatically.)

Another argument still being peddled mainly by academics is that Assad, for all his sadism, is fundamentally a rational actor who can be pressured into renouncing power through sanctions, international isolation and more diplomatic tough-talk. Let’s use the threat of referral to the International Criminal Court as an inducement to encourage political defections, runs the argument; never mind that Syria is not a signatory to the Rome Statute and a UN Security Council resolution is needed to refer regime officials to the ICC, an outcome Russia and China will ensure is never met.

At bottom, what the “soft landing” assessment fails to account for is that the regime better resembles a Mafia crime syndicate more than it does a despotic government. For the House of Assad, this is not a struggle between power and powerlessness but between life and death. “If you want to learn about Stalin,” says Irwin in Alan Bennett’s The History Boys, “study Henry VIII.” If you want to learn about the Assads, study The Sopranos.

I’m just returning from a conference on Syria in Copenhagen. The Syrians here understand the fallacies that underpin naive prescriptions for transition better than US and European policymakers, who continue to stress that they don’t want to further “militarise” the conflict. One wonders if the State Department and FCO expect civilians and defecting soldiers now being shelled with anti-aircraft artillery to take up Impressionist painting instead of Kalashnikovs.

“Eighty per cent of the GDP is now going to finance the army,” Amer al-Sadeq of the Syrian Revolution General Commission told me the other night from Syria. “Oil revenues have not been fully declared, and we suspect that India, Pakistan, Russia, Iran, and maybe even Iraq are now getting preferential energy deals just to keep the cash flow coming into Damascus. This is why sanctions won’t stop the regime from killing. Electricity goes out in the capital now as regularly as everywhere else. It’s because the state budget is going to maintaining the war machine.”

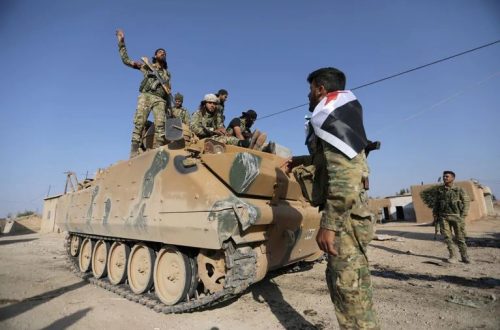

Amer estimates that 70 per cent of the bombarded areas are shelled indiscriminately. He cites the quasi-liberated town of Zabadani, which has faced “Korean rockets and cluster bombs that fall like small grenades; they explode when they hit the ground or when a human being comes in contact with them.” Sometimes, though, the regime chooses its prey. Amer says the ad hoc media centre in Homs was one. “I believe Marie Colvin and Remi Ochlik were deliberately targeted.”

Amer has several ideas for how to reconstitute Syrian security forces in advance of the regime’s collapse. Military defectors, he says, many of whom have fled to Turkey or Jordan, could be instrumental. One option the United States ought to consider is using their Jordan-based academies that professionalised both the Iraqi and Palestinian police forces for doing likewise with a new corps of Syrian cadets. Why wait to do this? Maintaining law and order will be an urgent post-Assad priority, particularly since reprisal killings and sectarian clashes are likely.

“If there’s no intervention, this revolution will be extended and very ugly,” Amer says. “A lot of people are going to die. It’ll be like Homs but on a massive scale.”