Cross-posted from Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi and Oskar Svadkovsky at Middle East Forum

Among the second wave of Arab Spring uprisings that followed Tunisia, Syria was the most spectacular “out of the blue” that suddenly arose in the face of the media and analytic community. Just days before Deraa exploded with protests last March, some analysts were still scrutinizing Syria’s circumstances and declaring the country to be immune from the Arab Spring. Nor did reporters who visited the country spot signs of a brewing storm.

In fact, throughout the Arab Spring, the media and experts repeatedly fell into the same trap of confusing the capital city with the whole country. On the eve of the Islamist landslide in Egypt’s elections various polls and informed individuals were putting the popularity of radical Salafis at between 5% and 10%. The Salafis have indeed won about 10% of the vote… but only in Cairo. Nationwide they took almost 30%, beating even those unrepentant pessimists who were betting on a Muslim Brotherhood spring. In some provinces they grabbed all of 50%.

This routine of the periphery ambushing the media and analysts during the Arab Spring and making a mockery of their reports and predictions has reached such grotesque proportions in Syria partly thanks to the media restrictions imposed by the regime, but mostly owing to the very peripheral nature of the Syrian uprising itself. This “peripheralism” has also laid waste to the best efforts of Iranian advisers who came to Syria to share with their Syrian colleagues the know-how accumulated by the regime in Tehran in crushing the Greens.

In truth, the escalation in Syria took by surprise only the people who never bothered to examine Syria’s population pyramid. It was no “out of the blue” to anybody even slightly familiar with the basic facts on demography and climate in the region. In the Middle East’s long list of hopeless basket cases Yemen is surely beyond competition. However, for quite a while Syria has positioned herself as a formidable contender for respectable second place.

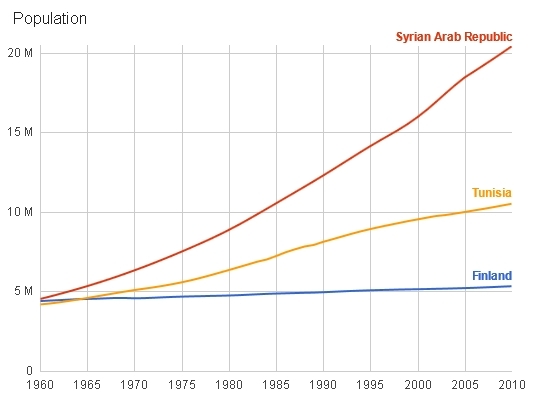

In some respects, the seeds of the current disaster were planted as far back as 1956, when Youssef Helbaoui — head of economic analysis in Syria’s Planning Department — famously declared: “A birth control policy has no reason for being in this country. Malthus could not find any followers among us.” Since then Syria has been living in a state of one uninterrupted demographic cataclysm. The regime was so obsessively pro-natalist that in the early 1970s, the trade and use of contraceptives in Syria were officially banned. By 1975, the birth rate reached 50 live births per 1,000 people, with Hafez al-Assad asserting that a “high population growth rate and internal migration” were responsible for stimulating “proper socio-economic improvements” within the development framework.

Even when other nations in the Middle East began to take measures to curb their population growth as the danger of demographic collapse started to loom over the region, the regime in Syria was struggling to make up its mind on the issue. Only in recent years has the regime introduced some measure of family planning, but by now the sheer amount of population momentum accumulated in previous decades has kept the population swelling to new highs. It’s true that the average Syrian woman entering the child bearing age now is expected to have no more than three children in her lifetime. Yet, the sheer proportion of such young people in the population continues to propel the population forward. And the workforce is still expanding at a neck breaking rate of 4%.

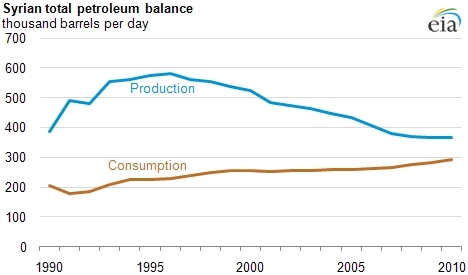

The impact of the rapidly mounting population pressures on the economy has been exacerbated by the steady depletion of natural resources that, critically for the regime, included declining oil production, with an output of 385,000 barrels per day (bpd) as of 2010 against the peak of about 583,000 bpd back in 1996. To give the reader some perception on the decline, even after hitting the bottom the oil sector still accounted for a majority of the country’s export income and about a quarter of government revenues.

The final blow came during the last decade. With Malthus sending broad smiles in the direction of Syria from his grave, the climate change that has hit the region has wrecked Syria’s countryside. Shifts in rain patterns have led to prolonged droughts all around the Middle East in recent years. But their impact was particularly devastating in Syria, where agriculture remains a major part of the economy and the lifestyle of a large section of the population, some 20% of Syria’s GDP being generated by this sector. With water shortages reported in many parts of the country, some rural areas have become impoverished disaster zones. Whole villages and fields have been abandoned, while slums around Syrian cities have been swelling with hundreds of thousands of climate refugees.

In 2009, the International Institute for Sustainable Development noted that a decline in rainfall and subsequent aggravation of water scarcity led to the abandonment of around 160 villages in northern Syria in the period 2007-2008. In eastern Syria, the Inezi tribe saw some 85% of its livestock killed between 2005 and 2010 because of prolonged drought. In 2010 the United Nations estimated that more than a million people have left the northeast of the country, “with farmers simply not cultivating enough food or earning enough money to sustain them.“

Basically, Syria’s GDP per capita was declining during the 1980s and stagnating in the 1990s. This trend was reversed only with the beginning of market reforms in 2000s, but the economic renaissance was largely confined to Damascus and Aleppo and struggled to spread to other parts of the country. A measure of prosperity brought into some cities by the economic liberalization, unevenly distributed in any case, was simply not enough to balance out the tremendous demographic and social pressures that were piling up in provinces like Deraa and Deir ez Zor and spilling into the center from the periphery. Regardless of whether the urban classes in Damascus and Aleppo were fully aware of their precarious existence living by the side of this volcano, they showed limited enthusiasm for fireworks once the volcano finally erupted and sent its flames towards the suburbs of their cities.

To be sure, the peripheral character of the uprising in Syria makes the task of ensuring the survival of the Assad regime rather difficult compared with the experience of its patrons in Tehran. However, getting rid of the regime would be an easy task for the country compared to surviving the post-revolution.

The uprising in Syria has many characteristics of a poor man’s revolt and a “periphery against center” conflict at the same time and as such it’s the exact opposite of the kind of unrest the regime in Tehran was facing in its big cities in 2009.

While the protest movement in Iran was led by the urban classes of the capital and major city centers, the Syrian uprising is very much powered by the same underclass that in Iran is providing the bulk of the recruits for the Baseej squads that eventually crushed the Green opposition. In Iran, Tehran was the epicenter of the protests, but the Syrian revolution started in the heavily Bedouin and undeveloped Deraa, and from its very beginning the uprising featured a rather unusual degree of mobilization in the countryside against the regime. Protests were regularly reported in villages and small towns. During the siege of Deraa and Hama, nearby villagers were reported trying to break blockades with supply convoys and clashing with security cordons.

Even where the Syrian regime was successfully keeping city centers clean of protesters, the unrest persisted in suburbs and the countryside. In far-flung provinces, towns and localities have been changing hands several times, with protesters and the Free Syrian Army reinfiltrating them immediately after the army had departed. The regime is clearly overstretched and struggling to contain such a widely geographically distributed and increasingly militarized unrest, as shown by the recent reports of unrest creeping in towards the centers of Damascus and Aleppo. More critically for the regime, the challenge of defending the country’s energy infrastructure over vast expanses of such a big country seems to be overwhelming the Syrian army, with attacks on oil and gas pipelines escalating.

Much was made of Syria’s sectarian configuration, which is indeed one of the most challenging in the region. The steady stream of reports about sectarian killings in Homs suggests mounting tensions and troubles for the future. Yet, even if stripped of all its minorities down to the bare Sunni heartland, the post-Assad Syria is still very likely to be resistant to any notion of unity and stability.

As a poor man’s revolt, the uprising in Syria, which by all accounts remains predominantly Sunni, is often blessed with the involvement of the most backward and conservative sections of the society. The Syrian opposition abroad may be represented by the finest intellectuals and members of all Syria’s minorities. However, a Voice of America reporter, recently allowed into one of the opposition’s strongholds in the area of Damascus-Douma, couldn’t help noticing how the place was teeming with fully veiled women.

Many parts of the Syrian periphery are severely impoverished and many are heavily tribal. The tribes in Deir ez-Zor are officially allowed to carry arms as a counterweight to the Kurdish population in the North. Tribes in Deraa and other provinces are also quickly becoming militarized.

The potential for internal conflicts over the country’s limited resources remains enormous. The same Deir ez-Zor, for example, is Syria’s poorest province. Yet Deir ez-Zor accounts for 70% of Syria’s oil production. Once the regime falls, the tribes in the province should be expected to demand their share of the oil revenues, either sending the rest of the country to beg the Saudis for a bailout, or starting a new “periphery against center” conflict.

None of this is to say that the survival of Bashar Assad’s regime is necessarily in the interests of the West, Syria’s neighbors and even the Syrians themselves. If only because it’s not obvious that Syria in its current configuration can survive at all. However, while the Western media can keep cheering on the Arab Spring and the triumph of liberal democracy in the Middle East until it’s blue in the face, the basic fact remains that this march to freedom in many parts of the region looks more like a modern species of a classic Malthusian collapse. Syria’s immunity to the Arab Spring was a short-lived notion. However, those who think that a better future beckons for the Middle East had better hope that by the time that future arrives Syria will be still hanging around.