by Joseph W

In 2007-8, I spent a year in Melilla, a city belonging to Spain in North Africa.

The city is brimming with the modernist architecture of Enrique Nieto, who famously designed key parts of Melilla’s main synagogue, mosque and cathedral. Melilla prides itself not only on its vibrant religious communities, but also on the quirky beauty of its religious architecture.

Here is Melilla’s Central Mosque that Nieto designed:

And here is the Or Zaruah synagogue, also designed by Nieto:

The curator told me that this was the most beautiful synagogue in all of Africa. It felt almost as if Nieto’s creativity was holding the city together. Throughout the past five centuries, Melilla has been a safe-haven for Jews escaping persecution in Iberia and Morocco.

However, over the past century, not all north-African Jews have enjoyed the relative peace and security that Melilla provides. Some, tragically, were the victims of pogroms.

A couple of years ago, I travelled from Melilla to nearby-Oujda, wandering around its majestic medina:

On 7-8 June 1948, a pogrom took place in Oujda, a Moroccan town close to Melilla in which four Jews were killed. Another pogrom took place in nearby mining town Jerada on the same day, where thirty-eight were killed, triggering a mass-exodus of Jews from Morocco, as 18,000 of the 265,000 Jews left for Israel soon after. This was a great shame as Morocco’s king had proved a great friend to the Jews by defying Hitler, and to this day Morocco encourages its citizens to understand the Holocaust.

Similar pogroms occurred in Syria, Bahrain and Libya from 1945-48, fuelled by tension and confusion surrounding the conflict in Palestine. In Palestine, reciprocal Jewish and Arab violence tragically led to the exodus of 700,000 Arabs from their homes in 1948. That same year, thousands of Jews had to flee the West Bank after Jordan annexed the zone.

I would imagine that the Jews of Morocco (and other countries) felt very much like the Arabs of Palestine. No home, exiled from their land and not of their choosing. Like their forefather Abraham, they would have to journey to places they had never known before – like their prophet Moses feeling like strangers in strange lands.

Above: Arab refugees 1948/Below: Jewish refugees 1948

Naturally, the Palestinian-Arab and the Arab-Jewish refugees regularly come up in political debates about Israel and Palestine.

This week, Israeli deputy foreign minister Danny Ayalon is calling for the Palestinian Authority to recognise the refugee status of Jews who fled Arab lands in 1948 – just as Israel should recognise the Palestinians who fled Israel in 1948.

On Comment is Free, Rachel Shabi responds to these remarks. She writes:

The reasoning is: if Palestinians think of themselves as refugees, forced to leave their homes in the tectonic shifts that created Israel in 1948, so, too, were the Jews exiting Arab lands in the same seismology.

There are all manner of problems with this formulation. First, many Middle Eastern Jews dislike being called refugees. Some reject this label because they left Arab lands out of a pioneering desire to relocate to what would become Israel; some say they were uprooted from Arab lands, either by agitating Zionist emissaries, or by the shockwaves that Zionism sent through the Middle East.

Of course, people dislike being called refugees. The word often carries a negative connotation, and I imagine there are Jews and Arabs anxious not to keep the tag of “refugee”. This does not mean one is not a refugee.

To deconstruct the “Jewish refugees” argument, Shabi gives two reasons for the Jewish exodus, both of which blame Zionism as a root cause.

It is true that the pogroms in Morocco occurred during a war in Israel. This does not mean the pogroms were simply the fault of Zionism. Rather, the people who carried out the pogroms should be blamed for the pogroms.

Aside from Morocco, consider Iraq. By 1951, over 100,000 Jews had fled to Israel. Was Zionism the reason?

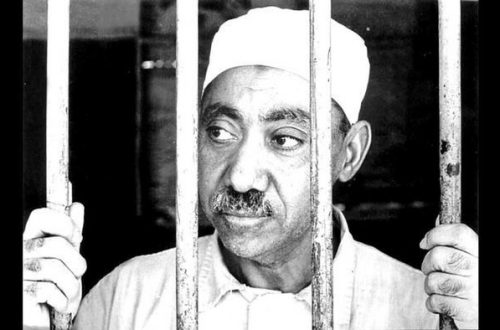

In 1941, a group of Nazi-sympathising officers staged a coup and overthrew the Iraqi regent. Inspired by the pro-Hitler cleric Mohammad Amin al-Husayni, they accused Iraqi Jews of being pro-British or pro-Zionist. Their threats came to a head with the farhud of 1st June, in which 128 Jews were killed and over 200 injured.

al-Husayni with troops

This led to huge Jewish insecurity in Iraq for years, which explains why most Jews chose to leave. Clearly then, Nazi influence – not Zionism – was the main reason to blame for the Jewish exodus from Iraq.

Shabi further argues:

Another thorn in the side of this argument is that Israel was created explicitly as a homeland for Jews, while for Palestinians, the homeland is the place from which they were exiled.

I think this is unfair on those Arab Jews forcibly exiled from their homes. Shabi is saying the Jewish refugees have less right to complain as they ended up in a Jewish state. That is not the point: they were still forced or pressured to leave their own homes.

Surely, many would have been happy staying put, yet were not given the option – the same being true for the Palestinian Arab exiles, who fled amidst fear and despair. And still, thousands of these exiles in Lebanon and Jordan are without homes, a situation in urgent need of rectifying.

And yet, I found this to be most objectionable part of Shabi’s article:

If Ayalon, or JJAC, or any of the other groups, were genuinely concerned for the history and legacy of Middle Eastern Jews, there might be better ways to express it. For instance, they might think about setting up heritage centres to commemorate Jewish life in Arab lands, or promote and celebrate their cultural, political and linguistic output, or address the ethnically-driven social imbalances that still exist in Israel between Jews of European and Arab origin.

Heritage centres to commemorate Middle Eastern Jews are wonderful projects. It is a fine thing, to celebrate Mizrahi cultural, political and linguistic output.

In Oujda, the city in Eastern Morocco I mentioned earlier, there is an 80-year old synagogue still standing:

The Jewish Morocco blog is calling for its restoration. Yet there are only six Jews living there – not even enough to form a minyan.

Remembering ‘linguistic output’ is worthwhile, but Sephardic languages like Lishanid Noshan, Judeo-Burber and Ladino will soon be extinct. Even in larger Jewish areas of North Africa such as Melilla and Casablanca, the communities are quickly diminishing.

Whilst it was great to see a lively Jewish community of Melilla, I am not sure there will still be a Jewish community there in another fifty years or so.

Focusing on Arab and Jewish cultural legacies is all well and good, but Arab and Jewish people are far more important.

Realistically, I do not think that refugees will accept cultural projects as compensation.

So, do we say to the Jewish refugees from Arab lands that they should not ask for compensation, but instead focus on their cultural heritage? I do not see whom that benefits.

By the same token, do we say to the Arab refugees from Israel/Palestine that they should not ask for compensation, but instead focus on their cultural heritage? This would be pointless too.

Clearly, wrongs have been committed on both sides, and both Jewish and Arab refugees merit compensation, or at least formal recognition of their refugee status. There are no easy answers, and the Jewish refugee and Palestinian refugee tales are not exactly the same, but that doesn’t mean one is somehow less relevant than the other.

Hopefully though, tragic tales of exile will never occur again, and Arabs and Jews may live as families in familiar lands.