You may have noticed that a new Democratiya is out.

I was particularly pleased to see a full translation of, and a proper response to, the André Glucksmann piece, Why I Choose Nicolas Sarkozy:

The ideological battle is done. Curiously, it took place on the right. More than a clash of egos, the Sarkozy – Villepin debate was indicative of two visions of France and of the world. In confronting the conservatives, Sarkozy made a clear break from the vacuous part of the right that is so accustomed to hiding behind pious concepts. To take a case in point, he advocates positive discrimination, flouting abstract ‘Égalité’ in order to stamp out real inequalities deriving from people’s skin colour, socio-economic background, or country of origin. Another example: he sets aside public money for building mosques, so adherents of the second biggest religion in France don’t have to worship in cellars or in buildings purchased for them by rich fundamentalists. Even if it means offending an established conception of the separation of church and state, remember that in 1905, France, with its tens of thousands of bell towers, knew nothing of minarets. Demand has changed, but supply remains the same. As society evolves, its principles must evolve in tandem.

…

But a large-hearted France has never forgotten the oppressed. Vietnamese boatpeople fleeing communism, the embattled Trade Unionists of Solidarity, those who suffered under Argentinean fascism, Algerians confronted by terrorism, victims of torture in Chile, Russian dissidents, Bosnians, Kosovans, Chechens… In no other country were these barbarities and the resistance to them discussed so much. Our ability to open our hearts to our brothers worldwide is etched into our cultural heritage – witness Montaigne, Victor Hugo, the ‘French doctors’ and those who would emulate them.Nicolas Sarkozy is the only candidate today to place himself in this large-hearted French tradition. He deplores the sacrifice of the Bulgarian nurses condemned to death in Libya, he denounces massacres in Darfur and the murder of journalists, and then states a principle of governance far removed from that of Jacques Chirac: ‘I don’t believe in what people call ‘realpolitik’, which rejects values and still doesn’t win any deals. I don’t accept what’s going on in Chechnya, since 250,000 dead or persecuted Chechens are more than a detail of world history. Because General de Gaulle wanted freedom for everyone, the right to liberty is theirs, too. To be silent is to be an accomplice, and I don’t want to be any dictator’s accomplice’ (14/1/2007).

How does the left respond? With few words, unfortunately. And what’s happened to the battle of ideas that for so long was its prerogative? Where has it mislaid the banner of international solidarity, once the pride of French socialism? I wish in no way to denounce Royal, a candidate whom I respect – even if I can’t swallow her opinions about the exemplary speed of the Chinese justice system. But the left finds itself grappling with a fissure bigger than itself, unhappy with those commentators and envious people who criticise its intellect or personality. The experience of April 2002 has not brought about any conceptual renewal within the Socialist Party.

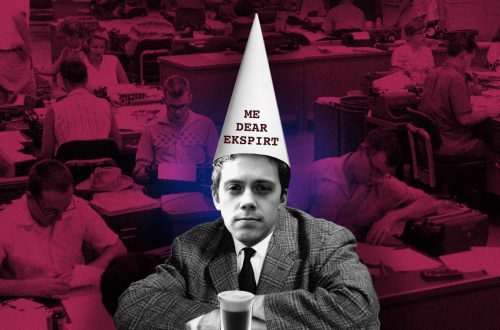

Philip Spencer does not agree:

The French left is not the prime culprit here. It is the French right which has been in government for several years and has colluded with such regimes. One can argue that Sarkozy has made some effort to distance himself from Chirac’s opposition to the Americans over Iraq, an opposition he called ‘arrogant’ rather than what it actually was – grossly hypocritical and grounded in past collusion with Saddam’s regime. This French government has been complicit, or worse, with several murderous regimes around the world, from Rwanda in the 1990s to the Sudan today. There is mounting evidence that the French knew about and abetted the plans of the Hutu Power genocidaires. Most recently it was the French government which welcomed Sudan’s President Omar al-Bashir with full pomp and ceremony at the very moment a global campaign was calling for his regime to be indicted for genocide.

Sarkozy is a powerful figure in this government. He may have differences with Chirac but he is not a candidate running against the machine or the right itself. He is the unchallenged leader of the right and a prominent figure in its government – Minister of the Interior no less. In that position, from which he has repeatedly said he has no intention of resigning (despite credible claims that he has abused it in the presidential campaign itself) he has openly flirted with racism against minorities, calling for the banlieues to be ‘hosed clean’. This was widely perceived as a semi-naked appeal to Le Pen’s voters on the racist right. At the same time, and perhaps almost as troublingly, he has made efforts to ingratiate himself with some of the most reactionary elements and leaders of France’s large Muslim population, funding organisations which they control and which repress Muslim voices, not least those of women trapped by patriarchal rules and controls over their bodies and movement. In funding such organisations, Sarkozy has given a further boost to a divisive communalism when what is most urgently needed is a strong defence of secularism and a robust commitment to civil liberties for all.