Maajid Nawaz and Ayaan Hirsi Ali first debated the motion “This House Believes Islam Is A Religion Of Peace” in 2010 for an Intelligence Squared event. They revisited the topic in 2013. Last night’s discussion – organized by the Alan Howard Foundation and staged at North London’s JW3 Jewish Community Center – was their third encounter, but the views of both participants seem to have evolved towards one another over time. The result was a discussion rather than a debate – one that covered a range of issues including multiculturalism, immigration, free speech, Cologne, honor violence, and Islamist antisemitism.

Today, Maajid does not offer platitudes about Islam being a peaceful faith and he tends to be critical of those who do (it is perhaps only fair to observe that in 2010 he was constrained by a clumsy debating motion, but I wonder if he would feel comfortable defending such a blunt proposition today, even for the sake of argument). For her part, Hirsi Ali no longer describes Islam as a religion with which we are at war. Nor does neuroscientist and new atheist moral philosopher Sam Harris, who recently co-authored a fascinating dialogue with Nawaz entitled Islam and the Future of Tolerance. “I admit” Harris tells Maajid during their exchange, “that I have often contributed to this narrative myself, and rather explicitly”.

On the larger question of religious reform, Hirsi Ali and Nawaz describe the religious and political landscape in similar terms. In his collaboration with Harris, Nawaz talks about Islam as a series of concentric circles of fanaticism and belief. At the center are global jihadists like ISIS and al Qaeda and local jihadists like Hamas, followed by a circle of revolutionary and political Islamists (Hizb ut-Tahrir and the Muslim Brotherhood, respectively), all of whom are working in their own ways to establish a theocracy, and marshal transnational Muslim support for their project. In her recent book Heretic, Hirsi Ali refers to the above as ‘Medina Muslims’ who draw inspiration from the warlike, triumphalist chapters of Muhammad’s life.

Outside of this circle are fundamentalist and conservative Muslims, who may hold highly regressive views on social issues, but who oppose State imposition of the Sharia. Conservative Muslims may not even be especially devout, Nawaz points out, but nonetheless feel profoundly hostile to Western cultural norms. Hirsi Ali calls them the ‘Mecca Muslims’ who draw their inspiration from the more-peaceful-but-not-necessarily-progressive chapters of Muhammad’s life. Nawaz and Harris and Hirsi Ali all agree that most of the world’s approximately 1.6 billion Muslims fall into this second category and that winning their hearts and minds to the cause of liberal democracy and pluralism ought to be of salience in the ideological struggle.

And then there are the progressive and reformist Muslims, a tiny and embattled band, who occupy the outermost circle. Hirsi Ali calls them the ‘modifying Muslims’, of whom Maajid Nawaz is one. Nawaz, Harris, and Hirsi Ali all agree that such people should be supported in their struggle for modernity and personal liberty, not least because the values they are struggle to advance and defend most resemble our own. “I want you to know” Harris tells Nawaz at the start of their dialogue, “that my primary goal is to support you”.

From a security point of view, the most pressing struggle is the one to contain the Hydra-headed Islamist movement, which will necessitate a lengthy counter-jihadist war and a longer effort to combat and, ultimately, discredit and destroy Islamist ideology. During the discussion at the JW3, Nawaz and Hirsi Ali both invoked the twentieth century’s utopian mass movements when discussing Islamism. At one point, Hirsi Ali compared Muhammad to Karl Marx, and she might have made more of this analogy; by 1964, Sayyid Qutb’s theory of revolutionary vanguardism was sounding a lot like Lenin’s. This understanding of Islamism as a movement partly shaped by totalitarian theory and ideology has helped move the counter-extremism discussion beyond a narrow consideration of religious texts and literalism in which conversation often seems to get stuck.

A second progressive front involves a quarrel about equality, liberty, and pluralism versus misogyny, separatism, antisemitism, and intolerance, which – while not explicitly political – are nevertheless detrimental to social cohesion and contrary to the protection of individual rights. Liberalism’s bygone battles with Christianity over the emancipation of gays and women and the freedom to blaspheme and disbelieve will need to be re-fought. This is partly a theological debate about the meaning and contextualisation of Islamic injunctions and the perfect nature of Muhammad. But it is also a cultural debate about notions of honor and shame, the rights of women and gays, the value of individual liberty, and the ethical limits of cross-cultural tolerance.

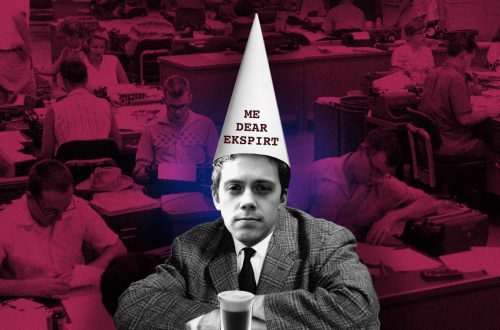

The difficulty is that those Maajid Nawaz calls ‘the regressive Left’ have neither the stomach nor even the inclination to defend their own social and political values. Instead, regressive leftists like C. J. Werleman and Glenn Greenwald – both atheists, incidentally – vehemently protect Islamists and fundamentalists and bitterly attack their critics for harbouring allegedly bigoted motives. Regressive leftists have nothing in common with the theocrats they defend, but – perversely – they believe this to be the point. Multiculturalism demands that we show a deferential understanding of difference, no matter how peculiar the traditions and customs of others may appear to us. To this, anti-Imperialists will add that Islamists are being unfairly attacked for speaking truth to power about the moral turpitude of Western foreign policy.

The fourth and final front of the wider struggle is against the West’s nativist far-right, populated by a nasty salad of neo-Nazi revivalists, sundry Pegida chapters, and demagogic populists like Marine LePen and Donald Trump. Such people tend to be dismissive of the reformers Nawaz and Hirsi Ali enjoin us to support. If they are genuinely and demonstrably liberal and open-minded, they are simply not thought to be Muslims at all – a rare and accidental moment of agreement with the regressive Left.

All of which leaves dissenters like Maajid Nawaz, apostates like Ayaan Hirsi Ali, and their liberal supporters like Sam Harris out on quite a limb. The support they do receive tends to come from the center-right and the surviving shards of a universalist and anti-totalitarian Left, otherwise smashed into powder by identity politics and moral relativity. Anguished cries of victimisation from Islamists and fundamentalists who find their political agenda and doctrines under sustained critical scrutiny are to be expected. Nor should minority dissidents be surprised by the distrust and indifference they receive from nativist reactionaries. But the bitterness of the regressive Left, discussed by Nawaz with Hirsi Ali last night and with Sam Harris in their book, is the especially venomous kind reserved for betrayal.

Parsing the various character assassination attempts on Hirsi Ali, Nawaz, and others over the years, it becomes obvious that ‘people of color’ who opt out of a life of angry victimhood are profoundly resented on the regressive Left who reserve for themselves the pieties of self-criticism. People like Nawaz and Hirsi Ali are expected to complain about Sykes-Picot and neo-imperialism and Islamophobia and to defend something called ‘postcolonial feminism’. Instead, they are in the habit of pointing out that Western foreign policy isn’t a sufficient or necessary precondition for Islamist terrorism, and that women in migrant communities and Muslim majority countries might not want to be subjugated in the name of tradition.

Their insubordination has been punished with accusations of dishonesty, bad faith, and bigotry. A recurrent and tiresome theme is that Hirsi Ali and Nawaz are motivated by nothing more admirable than a grasping desire to ingratiate themselves with a white establishment, and to this end they will happily serve a sinister anti-Muslim agenda. Allegations – often nothing more than insinuations – have been made that they have lied about who they are, that they don’t mean what they say, and that they are either greedy and self-serving or greedy and self-hating or both. A paradigmatic example of what the late Christopher Hitchens called “the pseudo-Left new style, whereby if your opponent thought he had identified your lowest possible motive, he was quite certain that he had isolated the only real one.”

To the contrary, what I observed at last night’s discussion, and what I found within the pages of Nawaz and Harris’s book, were people earnestly engaged in the complex task of figuring out how to understand and combat the rise of extremely dangerous ideas. This would be worth doing for its own sake, but the stakes involved may explain the nuancing of Hirsi Ali and Harris’s views. As atheists, after all, the most intellectually honest position is to simply denounce religion rather than to haggle over the value of competing sets of false claims. But as progressive thinkers and activists, Nawaz, Hirsi Ali, and Harris are also preoccupied with the pressing question of how to reduce the level of harm that fundamentalist and Islamist beliefs are currently generating, both within the increasingly unstable Muslim-majority world and restive Muslim communities in Western democracies. And, in this respect, they simply realize that the struggle of Muslim democrats, liberals, and reformers is also their own.