By Larkers A D

Last century a friend told me a story. His brother, like himself born and brought up in the English Home Counties, believed nevertheless that he was Scottish. The brother stopped speaking to anyone for days after seeing Peter Watkin’s film Culloden. This is a cinéma verité inspired style account of the battle in 1746 just outside Inverness that ended the Jacobite Rebellion against the British Crown led by Charles Edward Stuart, the better known ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’, an Italian Hungarian. Such was the brother’s identification with his ‘homeland’ the effect of the film on him was to send him into a depression. It is easy to dismiss this sort of reaction and once it could be. No longer. Now people chose to identify in ways that define themselves entirely by reference to events that, like a skirmish on that highland moor three centuries before, they have never experienced and whose effects they have never actually felt in the slightest. In this country, seemingly many thousands, perhaps even more, identified with one George Floyd who died on another Continent after a police arrest. Some few of those of us who cared about this enough to follow the reports still could not understand the outpouring of not just sympathy but self-abasement by thousands here who somehow blamed themselves, and the rest of us, for something we were and could not be responsible for unless by reference to a poorly understood and distant history with imprecise connection to a contemporary event: guilt by long gone association, embraced by an enthusiasm. (1) Such episodes are becoming ever more commonplace. Identity is the thing, experience is somewhat irrelevant.

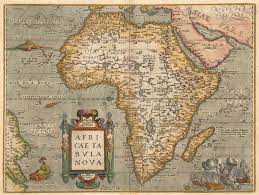

On the 12th October The Guardian printed an article in its Long Read series by Howard W. French. Professor French’s article (an extract from a longer study entitled Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans, and the making of the Modern World 1471 to the Second World War – an unambiguous claim, if somewhat ambitious, for a professor of journalism to make) in which Prof. French posits his thesis that modernity in Europe among white nations was made possible, only and entirely, by their collective exploitation of sub Saharan Africans. (2) This, on simple reflection, seems impossible to either prove or disprove since it depends almost entirely on research inspired by intuition and this experience Prof. French recounts whilst searching for a slave graveyard on Barbados, already responsible as he contends ‘whose slave-produced sugar, arguably more than any other place on earth, helped seal England’s ascension in the 17th century.’ (3)

‘With the sun racing downward in the western sky, I paced about, snapped a few photographs, and then finally collected myself as the wind whistled through the [sugar] cane. I tried mightily to conjure some sense of the horrors that had transpired nearby, and of the abundant wealth and pleasure that the sweat of the dead had procured for others.’

Prof. French has known only success and career prospects denied to many others by virtue of an accident of birth. But he identifies with a mass grave he says was otherwise hidden despite finding it via an old sign post. I expect the Professor’s book is replete with sources but there are none in his article as published. I also suspect his clothes were not made in Thailand or Vietnam of the present day sweat shops that procure our present ability to while away the fateful hours reflecting on long gone (we imagine) misery.

But my thoughts are not born from Prof. French’s research nor a fatality in another country that animated protests and riots around the western world, particularly the Anglosphere. It was growing long before. How real can such feelings be, that make people don suicide vests, plant bombs, desecrate and de-fenestrate statues to long forgotten figures and insist that cities from Sydney to Anchorage, from Cape Town to Aberdeen audit their place names for signs of racial supremacy? History is not a thing, but a constant study, subject to revision and development; it depends upon facts, records and a diagnostic approach, but is never settled; above all that there exists something we call truth and that the guardian of truth is denial.

When we lose objectivity, anything is possible and none of it needs to be real, merely felt.

1. q.v. The British Marxist left’s deep psychological obsession with Palestine, Gaza, etc. is based clearly on a need beyond analysis of fact.

2. My own interpolation; Prof. French in this exact makes no geographic distinction as I read him. Africa it is.

3. I viewed a television programme some decades ago where a similar search was made on a Caribbean island for British sailors of Nelson’s time, buried in unmarked graves, victims of diseases in their many hundreds. Universally, the poor do not have monuments to their lives.