Cathy Newman’s recent interview with Canadian Professor Jordan Peterson (I touched on his views in this post) has been much discussed on social media – you can watch it in full here. He does seem to attract a disproportionate amount of ire. Recently the Citadel Theatre in Edmonton refused to accept a booking for his book launch, for example.

I’ve only seen a couple of interviews with Peterson – so maybe I’m missing something – but I’m puzzled as to why he has quite such a toxic reputation. One problem is that his views are frequently exaggerated – in her recent interview Newman stated that Peterson insisted on misgendering transgender students. However (as I remembered from my earlier post) this is a misrepresentation of his position.

On balance, I agreed with those (including Douglas Murray) who criticised Cathy Newman’s interviewing tactics in this extended interview. But I do find some of Peterson’s emphases slightly odd. In particular he seems exercised by women who want a male partner they can dominate (3:45ff). I can’t say I recongize this as a specifically modern phenomenon. People of both sexes can be abusive or bullying (or nagging) and that’s always been the case. Where there has been a shift is in the number of wives who earn more than their husbands, and the number of men who take the greater share of parenting responsibilities. It might at least have been useful to point out that many men, certainly in the past, have also deliberately chosen a weak and compliant partner (as he suggests a minority of women do at 4:00), perhaps younger and less well educated.

In the gender pay gap discussion I think Peterson was correct to point out that the gap isn’t simply caused by discrimination. And Newman made a bad error in failing to engage with the point that women on average are more ‘agreeable’ (not a helpful trait when it comes to promotion) immediately pointing out that some women are not agreeable even though Peterson was explicitly drawing a generalisation (7:35). But Cathy Newman had earlier invoked the BBC case, and here the problem does seem, at least in part, to be a failure to offer equal pay for equal work. And even where direct discrimination isn’t in question there are ways in which the pay gap may be narrowed without immediately descending into a cultural Marxist dystopia. A simple example – the opportunity for flexible working could make a woman decide to remain full time after returning from maternity leave. More complex perhaps are issues of socialisation. Even if it seems demonstrably true that women are more agreeable, less combative, more attracted to less remunerative careers (all issues raised by Peterson), it’s less clear just how hardwired such differences are.

It was interesting that Peterson mentioned Sweden (13: 50) as an example of a country which, while very egalitarian, revealed a marked degree of sexual dimorphism in the job market – women dominate nursing whereas nearly all engineers are men. This, he suggested, was what happened when you gave people the freedom to choose. But the gender pay gap in Sweden is very narrow. Does this mean that they reward (perceived) male and female skills more equally than in other countries? Or perhaps those two professions are outliers, with others attracting more equal ratios. (And in fact Peterson’s figures don’t seem quite right.)

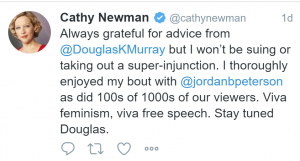

Returning to the interview, Newman puts words in Peterson’s mouth by saying he thinks ambitious women are miserable, then (15:50) unfairly asserts he wants to place barriers in the way of individual ambitious women. (This was because he had expressed uneasiness about statistically equal outcomes, which he thinks could only be achieved through authoritarian means.) She also wrongly (though perhaps understandably within the context of the conversation) accuses him of saying women are less intelligent than men (17:40). However she has since remained commendably good humoured in the wake of a good many derisory, and a few abusive, comments.