After a visit to the Burmese state of Arakan, Graeme Wood has written a chilling account for The New Republic of the horrific conditions suffered by the country’s Rohingya Muslims, even as Burma moves toward democracy.

(Appropriately, Wood received support for his visit from the US Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Center for the Prevention of Genocide.)

Although there has long been tension between the Buddhist majority and the Muslim minority in Arakan, the situation deteriorated rapidly after three Muslims allegedly raped and murdered a Buddhist girl in May 2012.

On June 4, 2012, not long after the alleged rape, Buddhists stopped a bus and invited non-Muslims to get off. Then they let the bus go on a short distance, stopped it again, dragged approximately ten Muslim passengers onto the street, and beat them to death. After that, the violence against Muslims became organized and genocidal. Buddhists launched coordinated attacks against Muslim villages and neighborhoods all over Arakan state. Dozens of Muslims from across Arakan told me similar stories: Buddhist mobs, protected by police, showed up screaming anti-Muslim slogans and demanding that the Muslims flee. They brought guns and knives, and the Muslims who stayed behind—in some cases because they were physically unable to flee—were shot, speared, and hacked. Some of the rest made it to other countries to start their lives over, but most of the displaced are in the dozens of squalid camps across Arakan state. The penalty for leaving these camps is three months’ imprisonment—if a Rohingya is caught by the cops. If caught by the wrong civilians, it could be lynching. The Buddhists burned the Muslims’ abandoned homes and possessions to cinders. Some Muslims eventually retaliated, and a much smaller number of Buddhists died or were driven into camps of their own after riots across the state.

Wood observes that the Western view of Buddhism as a pacifist religion has little basis in fact:

Buddhists have, in some circles anyway, received a free pass from skeptics of religion, largely because of the good p.r. and fine examples of the Dalai Lama and his herbivorous Western celebrity proxies (Richard Gere, Uma Thurman). The last few years of resistance to Chinese occupation of Tibet have seen 124 self-immolations by protesting Tibetan Buddhists, and zero burnings of Chinese soldiers. By now the average American thinks that Buddhist extremists are less dangerous than Buddhist moderates (a pleasant contrast with certain well-known types of extreme Christians and Muslims) and that the most violent living Buddhist is Steven Seagal.

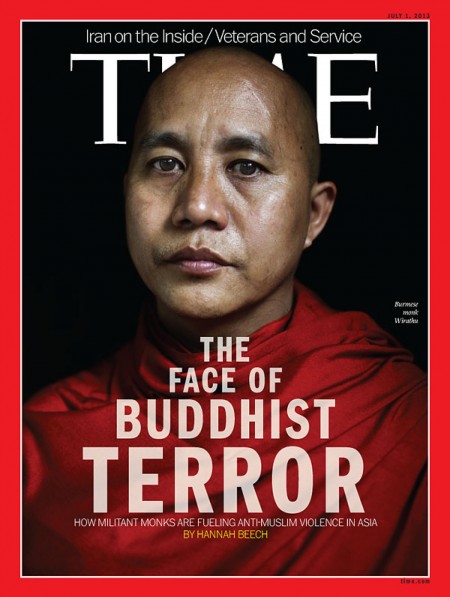

But violent Buddhist wack-jobbery is real—just ask the victims of Japanese fascism, which the Japanese Buddhist clergy supported rabidly—and in Burma it is flourishing. The country’s powerful clerics include a number of influential firebrands whose anti-Muslim alarmism sounds like the ranting of a saffron-robed Michele Bachmann. A Mandalay-based monk named Wirathu, the head of a Buddhist extremist movement known as “969,” appeared on a July 2013 Time magazine Asian-edition cover under the headline “THE FACE OF BUDDHIST TERROR.” “Now is the time to rise up, to make your blood boil,” Time quoted him telling his fellow Buddhists during the riots. The story called him “the Burmese Bin Laden,” a phrase that Wirathu-aligned monks I met in Rangoon seemed to think he should put on his business card.

Especially dispiriting is the near-total silence on these events from the leader of the movement for Burmese democracy, Aung San Suu Kyi. Wood suggests that she is either pandering to the Buddhist majority for political advantage, or– more troubling– as a Buddhist nationalist herself, she shares the hostility toward the Rohingya.

It should be a simple matter of decency and justice to oppose religious persecution and violence, whether Muslims (or any other group) are the perpetrators or the victims.