This is a cross post by Ben Cohen from Tablet

There is one memory of Norman Geras–the distinguished academic, prolific author and blogger, and doughty fighter against anti-Semitism and racism, who passed away in England earlier today–that has stayed with me for the last twenty-five years. It was a dreary afternoon in the northern English city of Manchester, late in 1988. About twenty students, nearly all of us professed Marxists, had gathered for Geras’s weekly university seminar on Marxism. As we discussed how class interests manifest in politics, one participant, who clearly wasn’t a Marxist, opined that not every owner of the means of production was hellbent on class warfare. Could we not accept, in his inimitable phrase, that there were “cuddly capitalists?”

Immediately, there were dismissive grunts and sycophantic glances in Geras’s direction. Surely the great Professor, on whose every word we hung, would rip this insolent pawn of the hated bourgeoisie a new one? But Norman Geras was not that kind of man. He answered with clarity and sympathy, artfully guiding the student through whatever text it was we were examining. In those few moments, the aspiring revolutionaries in his classroom were taught a salutary lesson on the enduring bourgeois values of respect, tolerance and kindness.

Geras was, to be sure, a Marxist and a man of the left. His books included a study of the Polish-Jewish revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg and an important treatise entitled “Marx and Human Nature,” in which he argued that Marx did, in fact, accept that there was such a thing as human nature, and that socialists consequently needed to grasp the ethical implications of this position.

Later in his life, Geras grappled on a daily basis with those ethical implications. A stalwart opponent of Stalinism during the Cold War, in its aftermath he emerged as perhaps the most tenacious critic of the western left’s embrace of dictators and tyrants from Slobodan Milosevic to Hugo Chavez, by way of Saddam Hussein.

The platform he used to express these views was, at least at the time he launched it, a novel one: a blog simply entitled“Normblog.” During the decade or so of the blog’s life, its austere design never once received a makeover, yet each day, thousands of readers would flock to read the latest posts by “Norm,” the name by which Geras became universally known. Norm’s interests–reviews of books and films and music, interviews with other bloggers about why they blog, ruminations on political philosophy, reminiscences of his favorite cities, observations about cricket, a sport he truly loved–more than anything else brought to mind the phrase flung by Stalin’s prosecutors against the Jews they loathed. For Norm, who was born in what was then Southern Rhodesia, and who spent the bulk of his life domiciled in the United Kingdom, was truly a “rootless cosmopolitan.”

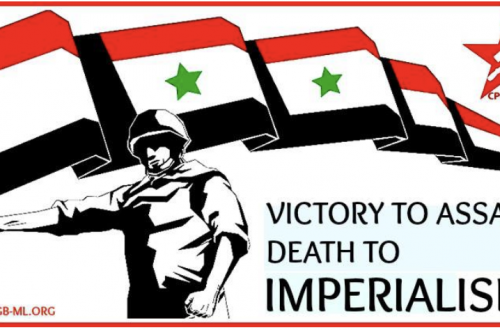

In challenging the orthodoxies of the left, Norm adopted stances that were denounced as heretical by his comrades in the Marxist academy, most especially the editorial board of the New Left Review, a journal he was long involved with before they parted ways over the issue of supporting authoritarian regimes in the name of “anti-imperialism.” In a 2004 post, “The last word on the Iraq war,” Norm restated the case for the toppling of Saddam’s regime in unabashedly moral terms. ”The most powerful reason in its favour was a simple one,” he wrote. “The regime had been responsible for, it was daily adding to, and for all that anyone could reasonably expect, it would go on for the forseeable future adding to, an immensity of pain and grief, killing, torture and mutilation.”

This sensibility was carried over into his writings on anti-Semitism, a subject he addressed with increasing frequency and urgency, given the vogue among some of his fellow academics for boycotting their Israeli colleagues, and more generally depicting Israel as the source of all evil. And in doing so, his Jewish identity was placed front and center.

In arguably his finest book on moral philosophy, “The Contract of Mutual Indifference,” Norm gently chided Rosa Luxemburg for her declaration that she had “…no special corner of my heart reserved for the ghetto.”

“A Jewish socialist ought to be able to find some special corner of his or her heart for the tragedy of the Jewish people,” he stated. “A universalist ethic shorn of any special concern for the sufferings of one’s own would be the less persuasive for such carelessness.”

What of Marx’s own anti-Semitism? Again, Norm’s instinct was to confront its existence, rather than ignore it. “The only reason for not facing up to these things,” he wrote, referring to Marx’s characterization of a rival thinker as a “Jew ni**er,” “is to protect Marx’s reputation as a thinker. But this is not a good reason, because it’s no protection; what’s there is there.”

“What’s there is there.” That may well be Norman Geras’s epitaph. Through his unfailing insight and disarming honesty, Norm was unique. And now that he is gone, it is safe to say that we will not see his like again.