This is a cross-post from Hopi Sen

Just over two years ago, western governments made a strategic decision about Syria.

We decided, collectively, to do nothing.

Oh, we would do everything we could to make it look like we were acting.

We would call meetings of the UN security council. We would summon conferences that never happened. We would give our blessings and our good wishes to those who opposed Assad, we would issue stern statements and pious press releases about the importance of human rights, democracy, and the need for negotiations.

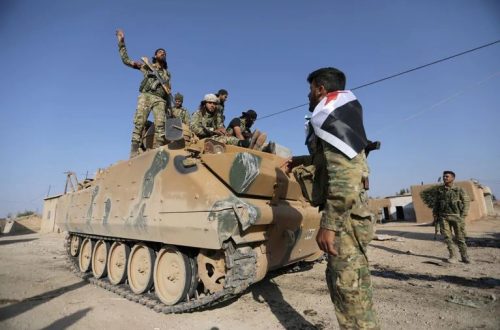

We would do all the things that had the appearance and form of activity, but when people were killed, when weapons were supplied, when forces were marshalled and dispatched, when outside forces intervened; in other words, when others actually did something, we would do nothing.

Perhaps we did this because we thought the regime would fall anyway. Perhaps we did it because we thought Iran and Russia would eventually tell Assad time was up. Perhaps we did it because we feared the consequence of a no fly zone, or of directly supporting the rebels. Perhaps we even did it because we thought Saudi Arabia would solve the problem for us.

Whatever the reasons, we made that decision.

Two years later, the UN reports that 93,000 people had died by April this year. They say this is a conservative estimate, and there may be another 37,000 dead, while 5,000 people are being killed each month.

If nothing has changed then, another six thousand people will have died since the UN report. This is before any attack on Aleppo, before any “mopping up” by pro-Assad forces in retaken towns.

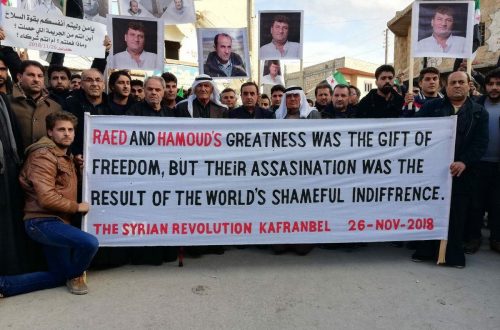

Do we feel responsible for our grotesque failure in Syria? Not a bit of it.

Indeed, we still seem to be pretending that somehow we have not failed. We debate earnestly the risks of arming the rebels, noting carefully the danger in aiding groups that our own inaction has made reliant on radicals and states whose interests have nothing to do with democracy. We talk of peace conferences, which are turning into a sick joke as the war-war goes on and on while the jaw-jaw is repeatedly delayed.

We have failed in Syria already. We have done nothing, and instead of feeling the shame of our failure, we choose to pretend it is not happening. Others see that weakness for what it is, and ruthlessly exploit it.

The last decade has been a steady retreat from intervention.

We know why. We saw the terrible costs of intervention first hand, while the deaths of the Marsh Arabs, the repression of the Kurds, the brutality of Saddam’s regime (and yes, our real-politik driven complicity in that regime) were somehow forgotten. We even managed to forget that the cost of containment was a society trapped by sanctions, a price worth paying for the containment of a regime we did not wish to overthrow.

Yet now, in Syria, we also see the price of inaction.

I make the following comparison not to compare the loss, or the war, or the justice of either, but to compare our reaction to each.

The rate of violent death in Syria is already more than double that in the bloodiest year of the Iraq war. Around 170,000 have died in Iraq in the decade since the war. More than half that are dead in Syria already, and the violent deaths are increasing rapidly. Where is the outrage of the humanitarian left? Where are the marches and the vigils? The petitions and the disbelief? Where are the Anti-War Marches?

Further, doing nothing has increased regional instability. Already Hizbollah are killing Syrian rebels, with who knows what consequences for Lebanon. Israel is both nervous of Islamism and of an unstable Syrian government. Turkey, Iraqi Kurdistan and Jordan are having to cope with some one and a half million refugees.

These are the results of the policy we chose.

Would things have been better if we had intervened directly? Would the slaughter have been less with a No Fly zone, or airstrikes on Syrian forces mounting aggression, or if we had supported secular, moderate rebels early? Would things have been better if we had even made it clear to Russia that there was some action that we would nottolerate?

That I can’t know, just as I cannot know what would have happened in Iraq this past decade if Saddam had been left to imprison and murder his people under a sanctions regime that killed innocent civilians in order to constrain their torturers.

No-one can really know “what if“.

The awful truth is that inaction and intervention both have terrible costs, and those who decide between them cannot ever truly know what will result. Some forgot that in the last decade, choosing to believe that only intervention could have a terrible price. I don’t forget the reverse now.

Just because the policy we have pursued has become a catastrophe does not mean the policy was undoubtedly and obviously wrong.

But by God, I wish we felt more shame for what we have not done for the people of Syria.