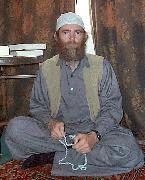

Many of you will remember the strange story of David Myatt, whose strange story is well chronicled by Wikipedia. In short: he was the leader of the British National Socialist Movement, the guru behind Combat 18, and the inspiration for the terrorist David Copeland. In 1998, however, he became a jihadist Muslim, a supporter of Osama Bin Laden and Hamas: a position which allowed him to continue to propagate his hatred of Jews.

Over the last couple of years, he has moved radically away from these positions.

Aymenn Jawad Al Tamimi summarises his present orientation:

Myatt no longer identifies as a Muslim at all. Indeed, on his blog, he speaks of:

My move away from Islam toward developing my own philosophy of The Numinous Way…

Further, in his autobiography ‘Myngath‘, he writes:

This change of my perspective – this personal change in me – arose, or derived, from several things: from involvement with and belief in, during the past decade, a certain Way of Life (Al-Islam), considered by many to be a religion….and it is only in the last few months that I have finally and to my own satisfaction resolved, in an ethical way, the dilemma of such a duty, thus ending my association with a particular Way of Life, which Way [i.e. Islam] many consider a religion.

Today, Myatt simply espouses a philosophy derived from what he calls ‘Pathei Mathos‘ (‘learning by experience’):

For what I painfully, slowly, came to understand, via pathei-mathos, was the importance – the human necessity, the virtue – of love, and how love expresses or can express the numinous in the most sublime, the most human, way. Of how extremism (of whatever political or religious or ideological kind) places some abstraction, some ideation, some notion of duty to some ideation, before a personal love, before a knowing and an appreciation of the numinous. Thus does extremism – usurping such humanizing personal love – replace human love with an extreme, an unbalanced, an intemperate, passion for something abstract: some ideation, some ideal, some dogma, some ‘victory’, some-thing always supra-personal and always destructive of personal happiness, personal dreams, personal hopes; and always manifesting an impersonal harshness: the harshness of hatred, intolerance, certitude-of-knowing, unfairness, violence, prejudice.

He even disowns Nazi ideology completely:

There is thus, based on applying the moral criteria of The Numinous Way, a complete rejection by me of National-Socialism – of whatever kind – and an understanding of Hitler as a flawed individual who caused great suffering and whose actions and policies where dishonourable and immoral.

I regard National-Socialism – of whatever variety – as an immoral set of beliefs, an example par excellence of hubris, with the Allied victory over NS Germany being a moral necessity, worthy of remembrance and celebration.

He also rejects Holocaust denial:

For decades – both as a neo-nazi and as a Muslim – I believed, I asserted, that the Shoah was a myth, a product of Allied post-war propaganda subsequently maintained and propagated by ‘Zionists’ (a modern NS code-word for Jews, designed to try and circumvent racial hatred legislation) in order to both establish the State of Israel and to enhance ‘Jewish power over Aryans.

[…]

With the expiration, in 2009, of the extremist I was, there was an openness toward this evidence, an empathy with the people subsequently met who had suffered because of the policies and the people of NS Germany and an empathy with those who had first-hand or familial experience of the horrors of the camps.Thus there is no longer any denial by me of the truth of those horrors, of the evil that was NS Germany. As someone once wrote: “Das war ein Vorspiel nur, dort wo man Bücher verbrennt, verbrennt man auch am Ende Menschen.

Finally, he writes on the West itself:

The simple truth of the present and so evident to me now – in respect of the societies of the West, and especially of societies such as those currently existing in America and Britain – is that for all their problems and all their flaws they seem to be much better than those elsewhere, and certainly better than what existed in the past. That is, that there is, within them, a certain tolerance; a certain respect for the individual; a certain duty of care; and certainly still a freedom of life, of expression, as well as a standard of living which, for perhaps the majority, is better than elsewhere in the world and most certainly better than existed there and elsewhere in the past.