This is a guest post by Matt Hill

In tribute to Christopher Hitchens. Incomparable secularist, humanist, polemicist. April 13, 1949 – December 15, 2011.

As this morning brought news of the death of a great secularist and humanist, it seems apt to recall a day in September 1928, when a bloody religious dispute broke out in Jerusalem’s Old City. History does not lack incidents which could illustrate the point equally well, but the one in question is distinguished by the particular triviality of its cause: a piece of cloth.

It was Yom Kippur, and the cloth was being used as a screen to separate male and female worshippers gathering for the service marking the start of the fast at the Western Wall. The Waqf, the Muslim religious trust which ran the Haram al-Sharif/Temple Mount, had banned any alterations to the site, and so demanded the screen be removed. Jewish leaders refused. The British authorities struck a seemingly reasonable compromise: it would stay up until after the evening service, and be removed in the night.

When a British officer found it in place at 7am the next day, he sent a ten-strong, fully armed police force to destroy it. Predictably, mayhem ensued. In the months that followed, protests and counter-protests broke out, leading to a wave of violence, strikes, and a diplomatic rumpus that involved telegrams to the League of Nations and letters to the king of England. Far be it from me to question the solemn importance of such ritual appurtenances; but I venture to wonder if the piece of cloth was quite worth the hundreds of Arab and Jewish lives lost in the affair – which, moreover, played its part in edging Palestine towards civil war and enduring tragedy.

Fast-forward to July 2000: the dying days of the Camp David talks, aimed at resolving the Israel-Palestine conflict once and for all. The negotiations are stuck on one main issue: the status of the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif. Bill Clinton begs Yasser Arafat to accept Ehud Barak’s latest offer: Israel will retain sovereignty over half of Jerusalem’s Old City; the Palestinians will rule over the Muslim and Christian quarters. But there’s a problem: Israel will not, under any circumstances, give up sovereignty over the holy compound. Clinton offers Arafat several sweeteners: the Dome of the Rock will have official embassy status. Arafat will receive a ‘sovereign presidential compound’ adjacent to the site. But Arafat is insistent: If anyone imagines that I might sign away Jerusalem, he is mistaken. I am not only the leader of the Palestinian people; I am also the vice president of the Islamic Conference. I also defend the rights of Christians. I will not sell Jerusalem.

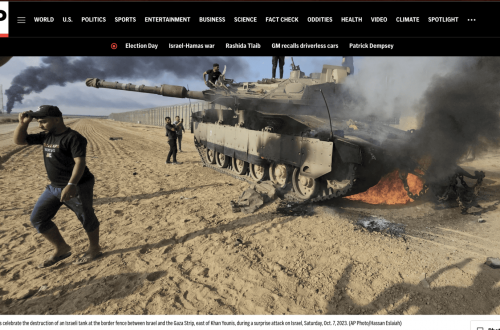

It’s become almost a cliche: everyone knows, roughly, the likely shape of a future peace deal between the Israelis and Palestinians. And it’s true that on issues like borders, settlements, even refugees, the chasm separating the two sides in 2000 has narrowed – even amid all the violence and overheated rhetoric. But then there’s Jerusalem. Its eastern half was annexed from Jordan after the 1967 war – illegally according to a unanimous ruling of the International Court of Justice – and proclaimed Israel’s ‘eternal, undivided capital’. Even if a rococo plan for divvying up the city’s Arab and Jewish neighbourhoods can be imagined, on one issue the experts scratch their heads. If an Israeli prime minister agreed to hand back the Temple Mount, he’d probably wake up a few days later an ex-prime minister. If a Palestinian leader agreed to surrender his people’s claim to the Haram al-Sharif, he’d wake up a few days later with a fatwa on his head. Peace seems destined to run ashore and splinter on thirty acres of holy stones. Meanwhile ordinary Israelis and Palestinians increasingly succumb to differing fundamentalisms to provide certainty in a baffling, violent world.

Hamas roughnecks detain young women for the crime of socialising with members of the opposite sex, while ultra-Orthodox Jerusalemites are ignorant of the grotesque associations of forcing women to the back of segregated buses. Both Jews and Muslims vandalise billboards and attempt to ban depictions of the female body – which, in both its real and imagined form, is inevitably the first target of the kind of sordid bigots who harbour a poisonous loathing of everything human.

I don’t claim moral equivalence: it’s true modern Judaism has nothing quite comparable to the depraved sado-masochistic cult of crypto-fascist necromania espoused by the most hard-line Palestinian Islamists. But the antics of Jewish mosque-torchers, price taggers, and hyper-Orthodox cowards determined to bully the less devout with their autistic scriptural literalism are almost as frightening, if only because they are partially shielded by a sophisticated modern state that seems reluctant to confront them.

Moderates on both sides will protest that such extremists are unrepresentative of their people and perversions of their faith. Perhaps so. But we should not underestimate how deep and tangled the roots of superstition are in these disputed lands. Fundamentalist parties have long enjoyed disproportionate power in the supposedly secular Israeli state, abetted by an electoral system that frequently makes its parties coalition power brokers. And the Palestinian leadership – likewise avowedly secular – may be close to losing its authority to an Islamic movement that it increasingly tries to outflank through mimicry. Religious fanatics – albeit of drastically different stripes – increasingly represent the id in the Palestinian and Israeli national psyche, cajoling the less devout into matching the intransigence they call faith.

One of the lessons of secularism is that the separation of church and state protects not just the state, but the church (or mosque, or synagogue) too. God and politics is an adulterous union that rarely ends happily ever after: what’s depressing is that it should be necessary to say so, urgently, in Israel in 2011. How the far-too-Holy Land could profit from the wisdom of Christopher Hitchens now – as both sides retreat into their bunkers of stubbornness and certainty, no longer able to hear the other across the abyss of no-man’s-land, all dialogue drowned out by the hymns of war.