As we observe today the 150th anniversary of the outbreak of the American Civil War, I want to recommend an article in The American Scholar by Adam Goodheart about the role of radical anti-slavery German and Middle-European immigrants in securing the city of St. Louis and the State of Missouri for the Union.

Politically… the newcomers were a class apart. Many had fled the aftermath of the failed liberal revolutions that had swept across Europe in 1848. Among those whose exile brought them to Missouri was Franz Sigel, the daring military commander of insurgent forces in the Baden uprising—who, in his new homeland, became a teacher of German and a school superintendent. There was Isidor Bush, a Prague-born Jew and publisher of revolutionary tracts in Vienna, who settled down in St. Louis as a respected wine merchant, railroad executive, and city councilman—as well as, somewhat more discreetly, a leader of the local abolitionists. Most prominent among all the Achtundvierziger—the “Forty-Eighters,” as they styled themselves—was a colorful Austrian émigré named Heinrich Börnstein, who had been a soldier in the Imperial army, an actor, a director, and most notably, an editor. During a sojourn in Paris, he launched a weekly journal called Vorwärts!, which published antireligious screeds, poetry by Heinrich Heine, and some of the first “scientific socialist” writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. In America he became Henry Boernstein, publisher of the influential Anzeiger des Westens. Though he may have cut a somewhat eccentric figure around town—with a pair of Mitteleuropean side-whiskers that would have put Emperor Franz Josef to shame—he was a political force to be reckoned with.

For such men, and even for their less radical compatriots, Missouri’s slaveholding class represented exactly what they had detested in the old country, exactly what they had wanted to escape: a swaggering clique of landed oligarchs. By contrast, the Germans prided themselves on being, as an Anzeiger editorial rather smugly put it, “filled with more intensive concepts of freedom, with more expansive notions of humanity, than most peoples of the earth”—more imbued with true democratic spirit, indeed more American than the Americans themselves.

…..

In effect, a small band of German revolutionaries accomplished in St. Louis what they had failed to do in Vienna and Heidelberg: overthrow a reactionary state government. And they had done it in a matter of weeks, while in the East the armies were stumbling toward a war of attrition that would last almost four years. If Lincoln and his generals in 1861 had been more like Lyon and his Germans, the Union’s conquest of the South might have played out very differently.

And later during the war, Abraham Lincoln corresponded indirectly with Karl Marx, writing on behalf of the International Working Men’s Association.

Lincoln’s views on labor would be viewed as dangerous apostasy by many of today’s Republicans.

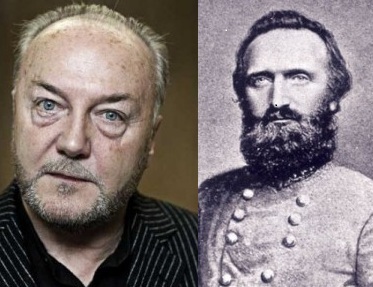

Which of course brings us to George Galloway, a Civil War buff whose favorite figure from that era is none other than the slaveholding Confederate general Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, with whom he feels a “very, very profound connection.”

As I wrote a few years ago:

Galloway’s ability to admire a man– however skilled and brave– who fought to preserve a horrific system of human bondage perhaps tells us something about his current willingness to admire and befriend those who he perceives as “rebels” and “fighters”– regardless of the brutal and ghastly things they stand for.