On Friday March 25, New Yorkers will gather to mark the 100th anniversary of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire.

According to The New York Times’s historical account:

It was Saturday, March 25, 1911. The work week was ending at the Triangle Waist Company factory in Lower Manhattan, and the men and women who operated the sewing machines and cut the cloth were pushing away from their tables, with some anticipating a night on the town and all looking toward their one day of rest.

On the 8th floor, flames suddenly leaped from a wastebasket under a table in the cutters’ area.

While workers frantically struggled with pails of water to douse it, the fire hopscotched to other waste bins and snared the paper patterns hanging from strings overhead.

The fire spread quickly — so quickly that in a half hour it was over, having consumed all it could in the large, airy lofts on the 8th, 9th and 10th floors of the Asch Building, a half block east of Washington Square Park.

In its wake, the smoldering floors and wet streets were strewn with 146 bodies, all but 23 of them young women.

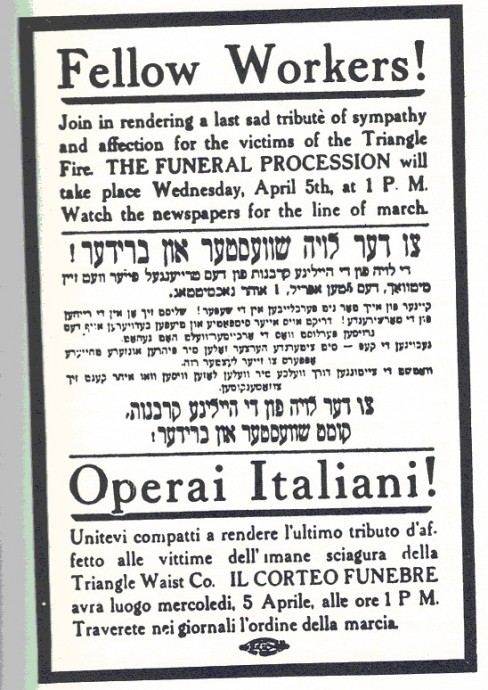

The Triangle shirtwaist factory fire, as it is commonly recorded in history books, was one of the nation’s landmark disasters, a tragedy that enveloped the city in grief and remorse but eventually inspired important shifts in the nation’s laws, particularly those protecting the rights of workers and the safety of buildings.The tragedy galvanized Americans, who were shaken by the stories of Jewish and Italian strivers who had been toiling long hours inside an overcrowded factory only to find themselves trapped in a firestorm inside a building’s top floors where exit doors may have been locked. At least 50 workers concluded that the better option was simply to jump.

…..

The company had become notorious two years before when its owners, immigrants themselves, managed to withstand a 13-week industry-wide strike, without giving in to demands for better conditions and union representation.The fire accomplished what the strike could not. From the city’s grief sprang government investigations and transformative legislation, first in New York State and then the nation.

The day after the fire, The Times reported:

The victims who are now lying at the Morgue waiting for someone to identify them by a tooth or the remains of a burnt shoe were mostly girls of from 16 to 23 years of age… Most of them could barely speak English. Many of them came from Brooklyn. Almost all were the main support of their hard-working families.

Almost all were Italian and Jewish immigrants.

Lest anyone think horrific working conditions in the American garment industry are ancient history, US Secretary of Labor Hilda Solis offered a reminder of a more recent event:

I had my own moment involving a sweatshop… In 1995, 75 Thai immigrants were freed from a so-called factory in the city of El Monte, Calif., part of the district I represented in the state Senate. They had been forced to eat, sleep and work in a place they called home.

Their employer confiscated their passports and kept them like slaves. Threatened with violence to themselves or their families, the workers hunched over sewing machines in dimly lit garages bound by barbed wire, sewing brand-name clothing for less than $2 an hour. Most of them were women.

I met them shortly after they were freed and heard their stories. And at that moment, the unthinkable became real for me. I had assumed that sweatshops were a thing of the past. But they had just spread…

Washington Post columnist Harold Meyerson reminds us of something else that hasn’t changed much– the resistance of employers to “burdensome” regulations on health and safety.

Businesses reacted [to the standards enacted after the fire] as if the revolution had arrived. The changes to the fire code, said a spokesman for the Associated Industries of New York, would lead to “the wiping out of industry in this state.” The regulations, wrote George Olvany, special counsel to the Real Estate Board of New York City, would force expenditures on precautions that were “absolutely needless and useless.”

“The best government is the least possible government,” said Laurence McGuire, president of the Real Estate Board. “To my mind, this [the post-Triangle regulations] is all wrong.”

Such complaints, of course, are with us still. We hear them from mine operators after fatal explosions, from bankers after they’ve crashed the economy, from energy moguls after their rig explodes or their plant starts leaking radiation. We hear them from politicians who take their money. We hear them from Republican members of Congress and from some Democrats, too. A century after Triangle, greed encased in libertarianism remains a fixture of — and danger to — American life.