Returning to David Patrikarakos’ baleful piece on the current situation in the DRC, and suggestions by her president, Joseph Kabila than MONUSCO should leave, in a previous blog-piece I discussed the ICC-trials arising from the Bogoro Massacre in February 2003.

The two senior commanders are Germain Katanga – former head the Patriotic Resistance Force in Ituri (FRPI), and an ethnic Ngiti – and Mathieu Ngudjolo Chui – one of Katanga’s senior officers as well as former head of the National Integrationist Front (NIF), and an ethnic Lendu. The strategically-placed village of Bogoro had been inhabited predominately by ethnic Hema, and by the Hema-led Union of Congolese Patriots (UPC).

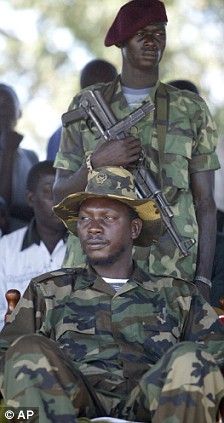

The best way to describe the various actors in the Ituri Conflict which these events formed a part, not to mention the wider chaos of the region over the past two decades, is by a simple weather report: “showers of bastards everywhere”. Following the adoption of the Rome Statute in 2002 and the authorization by what passed for a national Government in the DRC for the ICC to indict the various bastards, the first individual to be arrested under a warrant was, in fact, the founder and head of the UPC, Thomas Lubanga (pictured above).

In the weeks surrounding the Bogoro Massacre alone, the UPC stands accused of numerous attacks on other villages which resulted in several lesser mass-killings before being ousted from the region by Ugandan forces which the FRPI and NIS had been aligned, as well as earlier eye-watering killings of non-Hema for no reason other than that.

Whilst attempting to operate as a purely political operator, Lubanga was arrested by Congolese forces in March 2005 following the killings of nine Bangladeshi UN peacekeepers at Kafe village in Ituri Province almost two years to the day after the Bogoro Massacre, apparently by UPC militia (although, unlike Belgian UN peacekeepers who could express their contempt for UN power-structures which left 10 of their comrades to be massacre by the Interahamwe in April 1994 by spitting on their blue caps, all SE Asian rivalries were forgotten, as Bangladeshis and Indians and Pakistanis and Nepalese returned with devastating firepower).

His transfer to ICC custody came a year later, albeit solely on charges of using child soldiers. The narrowness of these charges have attracted criticism due to the lack of opportunity for victims of the wider conflict to see an individual interrogated and/or punished (cf. Jean-Pierre Bemba Gombo facing trial only for actions in the Central African Republic), but also due to the matter of Lubanga not having held direct operational command: although the Prosecution must therefore show he had personal responsibility and knowledge of the enlisting of children under 15 on the front-line, it is helped some what by his having had personal bodyguards as young as 10.

(A similar warrant was issued for Bosco Ntaganga, one of Lubanga’s senior commanders in the UPC and who remains at large in the DRC.)

Although Lubanga was the first to be arrested on behalf of the ICC, such restrictions meant that proceedings for his trial began less than two years ago. Since then, there has been a six month adjournment following complaints from the Defence team that the Prosecution willfully was withholding information, as discussed by one project in the Open Society Justice Initiative. Further in camera hearings meant that proceedings were further delayed, and will resume tomorrow, 6 December.

The same project discussed a visit by Joseph Kabila to Ituti Province in September, during which he attended a UPC rally. This was seen by the author as a crude attempt to court the Hema vote in advance of national elections next year, and could be linked with his call for MONUSCO forces to leave the DRC.

Large areas of the eastern DRC, not least Ituri Province, are by no means stable as seen with the mass-rape around the village of Luvungi, Kivu Province July/August by Hutu militia. Discontent at Lubanga’s trial amongst UPC loyalists and other Hema remains, and Kabila appears to be encouraging rumours that Lubanga could be released by the end of the year.

This is highly unlikely, and the inevitable disappointment could well inflame tensions once more. Even if Lubanga were to be released, or acquitted, Ngiti and Lendu chauvinists are liable to feel aggrieved as their fellows remain on trial; as they do already because of the much wider, and easier to demonstrate charges against Germain Katanga and Mathieu Ngudjolo Chui.