Simon Romero of The New York Times reports on Venezuela’s out-of-control homicide rate, and the Chavez government’s minimal efforts to deal with it.

CARACAS, Venezuela — Some here joke that they might be safer if they lived in Baghdad. The numbers bear them out.

In Iraq, a country with about the same population as Venezuela, there were 4,644 civilian deaths from violence in 2009, according to Iraq Body Count; in Venezuela that year, the number of murders climbed above 16,000.

Even Mexico’s infamous drug war has claimed fewer lives.

Venezuelans have absorbed such grim statistics for years. Those with means have hidden their homes behind walls and hired foreign security experts to advise them on how to avoid kidnappings and killings. And rich and poor alike have resigned themselves to living with a murder rate that the opposition says remains low on the list of the government’s priorities.

Far more urgent to the government, it seems, is to control the media’s coverage of the murder wave.

[A] front-page photograph in a leading independent newspaper — and the government’s reaction — shocked the nation, and rekindled public debate over violent crime.

The photo in the paper, El Nacional, is unquestionably gory. It shows a dozen homicide victims strewn about the city’s largest morgue, just a sample of an unusually anarchic two-day stretch in this already perilous place.

While many Venezuelans saw the picture as a sober reminder of their vulnerability and a chance to effect change, the government took a different stand.

A court ordered the paper to stop publishing images of violence, as if that would quiet growing questions about why the government — despite proclaiming a revolution that heralds socialist values — has been unable to close the dangerous gap between rich and poor and make the country’s streets safer.

“Forget the hundreds of children who die from stray bullets, or the kids who go through the horror of seeing their parents or older siblings killed before their eyes,” said Teodoro Petkoff, the editor of another newspaper here, mocking the court’s decision in a front-page editorial. “Their problem is the photograph.”

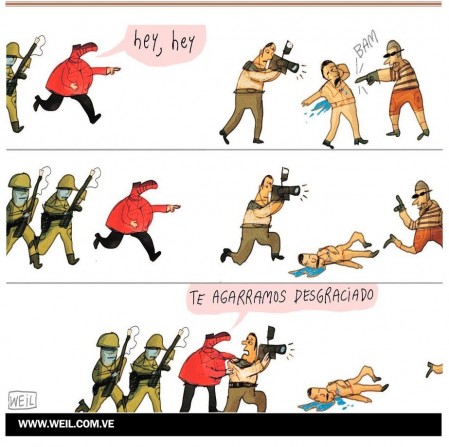

The Venezuelan cartoonist Weil makes the same point:

“We caught you, bastard”

“We caught you, bastard”Petkoff’s paper, Tal Cual, also published the morgue photo and, like El Nacional, is being sued by the government.

The authorities are also threatening an inquiry into “Rotten Town,” a video by a Venezuelan reggae singer [Onechot] that shows an innocent child struck down by a stray bullet. For all the government’s protests, the video has spread rapidly across the Internet since its release here this month.

Venezuela is struggling with a decade-long surge in homicides, with about 118,541 since President Hugo Chávez took office in 1999, according to the Venezuelan Violence Observatory, a group that compiles figures based on police files. (The government has stopped publicly releasing its own detailed homicide statistics, but has not disputed the group’s numbers, and news reports citing unreleased government figures suggest human rights groups may actually be undercounting murders).

There have been 43,792 homicides in Venezuela since 2007, according to the violence observatory, compared with about 28,000 deaths from drug-related violence in Mexico since that country’s assault on cartels began in late 2006.

Caracas itself is almost unrivaled among large cities in the Americas for its homicide rate, which currently stands at around 200 per 100,000 inhabitants, according to Roberto Briceño-León, the sociologist at the Central University of Venezuela who directs the violence observatory.

That compares with recent measures of 22.7 per 100,000 people in Bogotá, Colombia’s capital, and 14 per 100,000 in São Paulo, Brazil’s largest city. As Mr. Chávez’s government often points out, Venezuela’s crime problem did not emerge overnight, and the concern over murders preceded his rise to power.

But scholars here describe the climb in homicides in the past decade as unprecedented in Venezuelan history; the number of homicides last year was more than three times higher than when Mr. Chávez was elected in 1998.

Hugo Chavez has been president of Venezuela for 11 years now. And yet his spokespeople still blame the country’s death spiral on the policies of the government which left office in 1999.

Héctor Navarro, a former education minister who is now a spokesman for the ruling socialist party, says crime is a product of the neglect of youth under the pre-Chávez regime. Mr Briceño-León retorts that “they have a policy of blaming the previous government. But they don’t seem to realise that, after 11 years in power, they are the previous government.”

I’m among those who believe that– while effective policing and control of access to weapons are vital– there is an absolute link in a society between socioeconomic inequality and levels of violent crime. The question is then: why, despite Chavez’s heavy spending on subsidies and programs for Venezuela’s poor, have murder rates tripled since he took office?

Perhaps part of the answer is that while Chavez’s government has used some of its now-reduced oil wealth to subsidize the poor, and in some ways made their lives less bad, it has not to any extent helped the poor to escape poverty. By failing to invest in a diversified, job-creating economy, it has essentially condemned the poor to continued poverty– albeit with somewhat cheaper food and spotty health care. So despite Chavez’s socialist rhetoric, Venezuela’s poor masses don’t feel any more equal than they ever did. In fact by adding to the ranks of Venezuela’s extremely rich, his government may have worsened the problem.

But never mind. According to Romero the government “recently created a security force, the Bolivarian National Police, and a new Experimental Security University where police recruits get training from advisers from Cuba and Nicaragua, two allies that have historically maintained murder rates among Latin America’s lowest.”