This is a guest post by Dave Rich of the CST, and also appears on their blog.

The antisemitic incident figures released by CST today, which show an unprecedented number of racist incidents against British Jews in the first half of this year, should make everybody concerned with fighting racism and antisemitism pause for thought. The figures are startling and show a worrying pattern of rising antisemitism.

The incidents recorded by CST hold a particular message, though, for anti-Israel campaigners. The correlation between anti-Israel rage and antisemitic attacks, evident for some years, dominates the period covered by CST’s report. In January alone, 286 antisemitic incidents were reported to CST from around Britain. Over half of these made some reference to the fighting in Gaza, alongside the antisemitism. For comparison, during the Lebanon war of 2006, CST recorded 134 incidents in 34 days.

Let’s be clear: every one of the incidents recorded by CST as antisemitic is just that. Every one involves antisemitic language, or motivation, or the targeting of Jews per se, rather than pro-Israel groups or activists. We received many reports during the first six months of the year, of anti-Israel activity that we did not record as antisemitic incidents. There are examples of this on page seven of the report. Nor do we record anti-Israel, and arguably antisemitic, placards, banners or chants on demonstrations as antisemitic incidents. In total, in addition to the 609 antisemitic incidents recorded by CST, we received reports of a further 236 potential incidents that did not show evidence of antisemitism and were not recorded as such.

Let’s be clear about something else, too, before anyone makes the familiar accusation: this is not a call for anti-Israel campaigners to stop their activities, despite what some may claim. It would be wrong to tarnish all with a single brush. People are perfectly entitled to campaign against Israel and criticise its actions or policies, just as they are entitled to do so against the actions or policies of any other state. But that does not mean that they can disregard or contextualise any associated antisemitism in a manner that they would not dream of doing were it any other form of racism.

The spike in incidents recorded during January differed significantly from those across the first half of the year as a whole. Generally, they were more likely to involve targeted hate mail or abusive phone calls, rather than spontaneous verbal abuse or assaults; more likely to target symbols of the Jewish community and communal leadership, rather than random Jews in the street; and more likely to involve political motivation or ideology, rather than crude street racism. In other words, they are the hard edge of an antisemitic politics: directed against British Jews, but triggered by feelings about Israel.

It is worth remembering the extent of the rage against Israel during the fighting in Gaza. Anti-Israel demonstrations were peppered with banners and placards equating Israel with Nazi Germany:

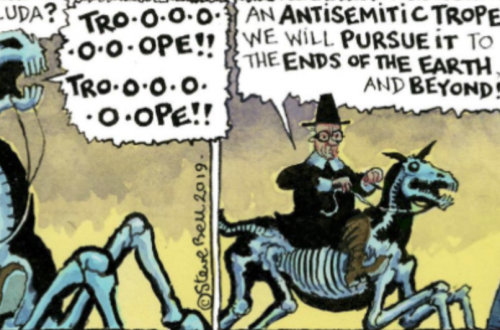

As the recent EISCA report, Understanding and Addressing the Nazi Card, argued, this equation is the most hurtful and extreme example of anti-Israel discourse. It is antisemitic in its impact, irrespective of the intentions of the purveyors of the imagery. And it has the effect of casting all Jews who do not actively disown Israel and Zionism, as being Nazis or Nazi sympathisers, in a cruel and wicked perversion of both history and trauma.

The Star of David, stripped of its place in the Israeli flag and left standing as a purely Jewish symbol, was fair game:

Other demonstrators expressed their feelings in ways that echoed, however unwittingly, more ancient antisemitic charges of infanticide and deicide:

There was the now-ubiquitous support for terrorist organisations:

And the idea that Israel represents a global power, and a threat to the whole world.

If the Israeli/Palestinian conflict is inflated to hold totemic significance for the entire world, then British Zionists – in reality, the vast majority of ordinary Jews – become recast as local agents of a global conspiracy, and it becomes impossible to discuss the conflict in reasonable terms.

In addition to this extreme discourse, the level of violence on display at some of the demonstrations, directed against the police and local shops, was shocking.

Nothing of this sort was seen during the Lebanon war of 2006, or on the demonstrations against the Iraq war three years before that. Starbucks in particular was a favoured target of the protestors, due to the mistaken belief that it has strong economic connections to Israel.

There is no way of knowing if any antisemitic incident perpetrators attended these demonstrations, or were influenced by them. However, it is hard to believe that there is no connection between the three simultaneous phenomena in January, of an unprecedented number of antisemitic incidents; an unprecedented level of extremist discourse around Israel; and an unprecedented level of visible anger and violence at anti-Israel demonstrations. It is possible that all three occurred in parallel with each other as responses to the same stimulus, but seems implausible that they had no relationship to, or impact on, each other. If the antisemitic incidents sparked by reactions to events in Gaza were of a predominantly political character, then these demonstrations, widely reported in the media, provided the environment and energy that all types of hate crimes feed off. If the level of anger these demonstrations could generate this kind of violence against Starbucks, then how much more likely is it that it also led to attacks against Jews?

The point of this post is not to silence or gratuitously attack anti-Israel campaigners; nor is it to make over-simplistic comparisons between antisemitism and anti-Israel activity. It is simply, as stated in the first paragraph, to give food for thought about the dynamic between the two, which is often complex and unclear, but cannot be ignored.

It should be possible to campaign against Israel’s policies and actions without using the most offensive and inflammatory discourse. For example, several anti-Israel campaigners have made the point that they compare Israel to Nazi Germany not because they think it is factually correct, but because they know it will elicit areaction. They are right: it elicits many different reactions, in different audiences. It gets attention, certainly, which is often the main intention; it offends most Jews (which is often not the intention) while inducing a taboo-busting thrill in those who make it. In addition, it is possible that, unwittingly, it incites a smaller but significant audience to hate and attack Jews. Certainly, it brands ‘pro-Israelis’, however defined, as today’s Nazis, deserving of the same ostracism from decent society.

There are several different ways to respond to this. One is to shrug your shoulders: the suffering of Gazans is much worse than that of British Jews; antisemitism will exist for as long as Israel behaves as it does, so the argument goes, and there is not much that can be done about it. For people who consider themselves anti-racists, though, this should not be the answer. Antisemitism, like all forms of racism, is not an acceptable by-product of political campaigning. Allowing antisemitism to become more acceptable than other forms of racism damages all of society, not just Jews.