This is a cross post from Socialist Unity and the Morning Star

Sixty years ago the German Democratic Republic was created out of the Soviet Zone of occupied Germany in response to the introduction of a separate currency in the Western sectors and the go-it-alone creation of the Federal Republic in September 1949 It lasted until 1990 when the people voted to accede to the Federal Republic.

The first GDR government was composed of individuals with a track record of active opposition to the nazi regime. Many had spent years in concentration camps, prison and exile. They returned determined to build a democratic, anti-fascist Germany.

It began life at a great disadvantage compared with West Germany. It comprised only a third of German territory with a population of 17 million, as against 63 million in the west, and was considerably poorer, having little heavy industry and few mineral resources.

One of the GDR’s greatest achievements was the creation of a more egalitarian society. Measures were introduced to counter class and gender privilege and increase the educational and career prospects of working-class children.

As a result, the GDR became probably the most egalitarian society in Europe. Full gender equality and equal pay were also enshrined in legislation. Pay differentials between different groups of employees were minimal so that even top managers or government ministers were hardly wealthy in Western terms.

Even in terms of housing, economic and class difference played little role. All areas contained a mix of professional and working-class people. This lack of large wealth differentials and class privilege made for a more cohesive and balanced society.

For some such egalitarianism was not amenable and the lure of higher salaries and business opportunities in the West remained strong. This led to a steady haemorrhaging of skilled workers and professionals before the wall was built in 1961.

The GDR was a society largely free of existential fears. Everyone had a right to education, a job and a roof over their head. Emphasis was placed on society not on individualism, and on co-operation and solidarity. This process of socialisation began with nursery children and continued through school and into the workplace and housing estates. The government argued that the workers who produced the commodities that society needed should be placed at the forefront of society.

Those who did heavy manual work, such as miners or steel workers, enjoyed certain privileges – better wages and health care than those in less strenuous or dangerous professions such as office work or teaching. There were workplace clinics, doctors and dentists attached to large factories and institutions. The workplace and trade union were largely responsible for ensuring medical care, the provision of leisure and holiday facilities and childcare, even down to the most personal issues of finding accommodation. The trade union owned and ran a whole number of rest homes, sanatoriums and holiday accommodation used by the workforce and their families for nominal prices.

This system helped to solve working parents’ problems of caring for their children during school holidays. By the 1980s around 80 per cent of the population was able to go on some form of holiday, although most of these would be taken in the GDR itself, many in one of such centres at very low prices. No worker could be sacked, unless for serious misconduct or incompetence. However, even in such cases, other alternative work would be offered.

The other side of the coin was that there was also a social obligation to work – the GDR had no system of unemployment benefit because the concept of unemployment did not exist. Pay levels in general were not high compared with Western standards. But everyone knew that the profits they created would go into the “social pot” and used to make life better for everyone, not just for a few owners or shareholders who would pocket the surplus. Most people recognised that the surplus they created helped increase what was called the “social wage” – subsidised food, clothing and rent, cheap public transport and inexpensive tickets for cultural, sporting and leisure activities.

The idea of a social wage is a vital concept for any society purporting to be egalitarian. It was instrumental in ensuring the implementation of greater social equality, undermining privilege and class hegemony. Although most people lived in rented accommodation at controlled and affordable rents, a considerable minority owned their own houses and some built their own privately owned houses. Rents remained virtually unchanged over the life of the GDR and no-one could be evicted from their home. There was therefore no homelessness or fear of becoming homeless.

From a country with few raw materials and an underdeveloped industry devastated by the second world war, the GDR rose to become the fifth strongest economy in Europe and among the 10 strongest in the world. The economy was characterised by central planning. This enabled the government to plan growth, set priorities and determine where to invest, but there was the downside that such centralised planning on such a scale could be inflexible and cumbersome. However, a vital factor holding back the GDR economy was a strict boycott by Western governments, preventing the export of advanced technology.

Over 90 per cent of all assets in the GDR were owned by the people in the form of “publicly owned enterprises” (VEBs). By contrast, in the Federal Republic a mere 10 per cent of households owned 42 per cent of all private wealth and 50 per cent of households owned only 4.5 per cent.

After the war, large estates owned by the former landed aristocracy, the Junkers, were broken up. Five hundred estates were expropriated and converted into co-operatives or state farms and thousands of acres distributed among 500,000 peasant farmers, agricultural labourers and refugees. Later the government encouraged, sometimes cajoled and pressured farmers to join co-operative farms, but farmers retained ownership rights to their land. By 1960 nearly 85 per cent of all arable land was incorporated into agricultural co-operatives. In 1989 there were 3,844 agricultural co-ops and these were one of the big achievements of the GDR, proving to be efficient and better for the workforce. For the first time in history, agricultural workers were freed from round-the-clock work just to make a living.

With agricultural co-operatives run on an industrial scale, workers enjoyed fixed-hours working and shift systems, had regular holidays, childcare, training opportunities and workplace canteens. All this certainly helped stem the flight from the countryside to the towns. For the first time in Germany, women enjoyed completely equal rights with men, both in their personal sphere and the workplace.

They were provided with the means and opportunities of developing their careers and personalities beyond or instead of their traditional roles in the home, as wives, mothers and daughters. Some 91 per cent of women between the ages of 16 and 60 were in work.

Most women viewed success in their careers as a main source of fulfilment – this is about the same percentage as for men. Some 88 per cent of all adult women worked and a further 8.5 per cent were in full-time education. Most women were also highly skilled. Only 6 per cent had no qualification at all, whereas in the Federal Republic 24 per cent had none.Despite these figures, in the top echelons of government and party male patriarchy still persisted.

The country’s record on internationalism was exemplary. It took the idea of solidarity with other, struggling nations seriously. It sent doctors and other medical staff to the front line in Vietnam, Mozambique and Angola. It gave engineering, educational and military support to many countries.

It also gave numerous foreign students from countries struggling to free themselves from the legacy of colonialism free training and education in the GDR.

Of course the GDR had a whole number of serious shortcomings and in terms of individual rights and democracy left a lot to be desired.But to dwell only on these aspects as the mainstream media in the West has done, is to ignore its genuine achievements.

Since its demise, many have come to recognise and regret that the genuine “social achievements” they enjoyed have now been dismantled.

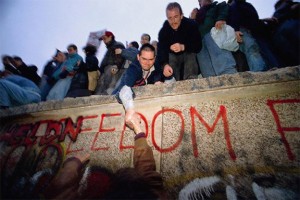

Unfortunately, the collapse of the GDR and “state socialism” in 1989 came just before the collapse of the highly lauded “free market” system in the West.

John Green and Bruni de la Motte have just written a new booklet, Stasi Hell Or Workers’ Paradise? Socialism In The German Democratic Republic – What Can We Learn From It? Available from the Morning Star

(Propaganda and lies)

UPDATE

Over at Socialist Unity, Comrade Nick Wright of the Communist Party of Britain has a dream:

Imagine a socialist Britain.

Private education is abolished and the children of workers are given privileged access to higher education.

Private medical care is abolished and doctors and dentists wages brought closer in line with average earnings.

Landownership (apart from private houses and co-operative farms is abolished and rental income made illegal. An upper limit is placed on the number of employes an enterprise is allowed to employ and profit levels are highly taxed.

The private export of capital is outlawed and profits from overseas investments is government controlled and highly taxed.

Most employment in the City is ended and the skilled labour thus displaced is directed into public service jobs

banks are nationalised and farmers incentivised to join co-ops or, in the case of big farms are taken in pubic ownership.

Anybody care to guess what proportion of the British population might want ti migrate to say, Germay.

Racist and fascist propaganda is outlawed and it expression attracts severe penalties.

The military, police and security services are purged of people whose loyalty to the socialist government is in doubt

What a lovely country this would be. Let us hope that one day the Communist Party of Britain attains power.