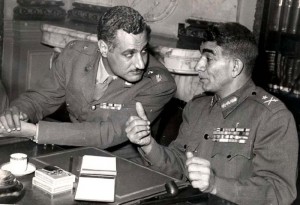

For 50 years historians have debated the question of what motivated Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s disastrous drift towards a humiliating defeat in the Six-Day War with Israel in 1967. Gabriel Glickman argues that the archives suggest we have underestimated the pivotal role of Nasser’s vendetta against America in driving Nasser’s actions. Current American and Israeli officials, he advises, should take note of this episode as a lesson in how history can play out when the US tries and fails to turn a formidable foe into a friend. With US policy now tilting towards the Sunni states and an angry Iran possibly left out in the cold, Glickman’s essay has more than historical interest.

Decisions leading to war are rarely understood without the benefit of documentation to show exactly what officials were thinking. However, in the case of the Six-Day War, historians have overlooked what has long been staring them in the face: Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser mobilised his army against Israel in mid-May 1967 in part to get back at the US for refusing to provide economic aid that the Egyptian leader so badly needed after years of wasteful spending on ‘Egypt’s Vietnam’ in Yemen. Not only does this challenge the conventional notion that Nasser acted to stop an alleged Israeli plan to topple the radical Baath regime in Syria, it demonstrates the limits of a US foreign policy that relies on appeasement to turn adversaries into friends.

To begin with, US President John F. Kennedy’s officials dealing with the Middle East believed that a close personal relationship between the president and Nasser, and generous amounts of economic aid without attached strings, could buy the Egyptian leader’s loyalty. However, in spite of an unprecedented three-year credit agreement, Nasser refused to disengage from Yemen, where he was locked in a proxy war against Saudi Arabia for regional mastery. Unlike his predecessor, however, Lyndon B. Johnson (who took office at the end of 1963) had little regard for ‘personal diplomacy’. If Nasser wanted to continue receiving American economic aid, he needed to withdraw from Yemen. Thus, when Nasser still failed to make progress on Yemen even after receiving a new six month credit agreement following the expiration of the original one, Johnson and Secretary of State Dean Rusk hesitated through the end of 1966 and the beginning of 1967 to approve Nasser’s request for more aid. Evidently, Nasser resented being made to wait. He considered the delay an indication of American imperial pressure and readily turned to the very issue that US officials had sought to circumvent through years of aid: Arab liberation of Palestine. READ MORE.

Also in Fathom 16 on 1967:

The international media and the Six-Day War, by Meron Medzini

As long as the Arab world views Israel as a temporary aberration to be conquered, Israel will stand fast, by Einat Wilf

Internalising defeat – the Six-Day War and the Arab worlds: an interview with Kanan Makiya

The wisdom of Resolution 242, by Toby Greene

Remembering the Six-Day War, by Michael Walzer