Since I last posted on this topic the full poll results have been published, Trevor Phillips’ documentary has been broadcast and a great deal of ink and airtime have been devoted to dissecting the results.

I had quibbles with the programme – but still more quibbles with many of its detractors. So here are a few reflections, with links to just some of the many comment pieces – good and bad – generated by both poll and programme.

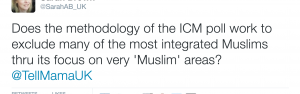

Methodology

As Iram Ramzan observes at the opening of her recent robust post:

This was the week when British Muslims became experts in research methodology.

One now familiar point struck me when I first read the methodology section appended to the initial article.

It’s not clear to me how different the poll would have been if it hadn’t limited itself to these areas. However if there had been a discrepancy it presumably would have been in the direction of tolerance and secularism, so it’s not surprising that liberal Muslims, in particular, raised this point.

Other methodological criticisms seemed like special pleading, such as complaints about sample size. The NSS’s Benjamin Jones, after pointing out that as many Muslims sympathise with suicide bombers as favour the right to publish images of Mohammed, is surely right to call out double standards here.

If a poll of 1000 UKIP members had found majority support for criminalising homosexuality, would anybody on the left be quibbling about the methodology of the poll? If poll after poll kept suggesting that a sizeable block of UKIP’s 3.8 million supporters wanted to ban homosexuality, it is inconceivable that this would not be a cause for serious concern and scrutiny. The criticism would be totally unrestrained.

This, from Anthony Wells, seems sensible.

I’ve seen and heard several people grumbling that if you had polled other faith groups you would have come up with similar findings. However the suggested groups are always subsets – Baptists, Catholics, Hasidic Jews – so, even if this is true, the data wouldn’t be comparable with a poll of all British Muslim opinion.

Age of respondents.

There was some discussion, following my previous post, about the correlation between (il)liberal views and age. The poll threw up mixed results here. In response to some questions – such as those on homosexuality – there was a hearteningly steady correlation between youth and comparative liberalism., though still of course a disappointingly large gap between young Muslims and non-Muslims. Generally there was also quite a strong correlation between being older and holding conservative views. However another pattern was the parabola – on some issues the most liberal views were held by the middle aged or middle youthed. It’s hard to know whether this is a sign of regression or whether the views of today’s young Muslims will mellow in time.

It would take a long time to analyse the age data in full but, having sampled it when I first looked at the poll, although the news isn’t all good I’d rather stick with what we’ve got than see a complete reversal of the pattern – i.e. see a set of poll data in which young Muslims held the views now held by their elders.

The programme itself

There were most certainly some positives. Genuinely liberal Muslim voices were given a generous share of airtime. Some of the ‘tough’ points raised by the programme were fair enough – yes, truly liberal voices are a minority and this fact needs to be confronted, not anxiously avoided. But perhaps – without compromising rigour – more could have been done to ward off easily anticipated criticisms. I’m sure the following points will irritate many readers, but why do you want to give people any excuse to ignore what’s really important here? Why not make the programme as fair and calm as possible?

For example, given that support for terrorism wasn’t the key issue thrown up by the poll, it might have been better not to start with footage relating to 7/7. The reconstruction of a polling interview didn’t add much and it was clear the fictional interviewee was no liberal. Couldn’t a more liberal (and less morose) fictional Muslim have been added to the mix if it was felt viewers really needed this kind of diversion?

Although howls of bias were over the top, there was some scope for a little more accentuation of the positives, alongside the fully necessary dissection of the negatives. For example, as well as emphasising the 17% of Muslims who want to lead largely separate lives it would have been good to remind us that many Muslims want no such thing.

And for balance, a bit more use could have been made of moments when the control poll worked to soften Muslim responses. Although only 34% confirmed they’d report concerns with friends getting drawn into terrorist circles to the police, many were quick to point out that still fewer non-Muslims – 30% – gave the same answer. It could be countered that this is a less charged anxiety for non-Muslims – that they found it more difficult to envisage a friend inclining to terrorism – but it was one of the biggest flaws in the programme that it failed to acknowledge the similarities between the two polled groups on this important issue.

The rhetoric could have been toned down at times.

Once we look deeper into the survey results we actually find a chasm has developed.

While the negative findings needed to be tackled head on – no question – this way of phrasing the mix of positive and negative responses seemed to privilege the negative. It’s fine to point out that the negative responses were elicited in response to more questions or to more important questions but not to assume that negative responses were automatically more telling. Perhaps it was this aspect of the programme – ‘what lies beneath’ – which led some to claim that the title was conspiratorial, invoking, perhaps, taqiyya.

The question here implies that, whatever your Muslim neighbours may tell you, don’t believe them.

As someone who shares the concerns voiced in the programme, I’d have welcomed some adjustments which made it more likely that those more unwilling to acknowledge the problems would start to shift their views without feeling that to do so was pandering to anti-Muslim prejudice.

This comment from Trevor Phillips particularly struck me on first viewing.

“Others do hold views on some issues which look a bit more like the rest of Britain’.

There was absolutely no need to be so grudging here. Now they may be a much smaller minority than most of us would like, but there clearly is a liberal core of British Muslims who have views on all issues which are fully like the rest of Britain (apart from those non-Muslims Britons who are themselves illiberal of course.)

Media responses

Bigots and the far right have revelled in these results. Katie Hopkins was on her usual toxic form:

I sat down to watch ‘What British Muslims Really think’ with my best multicultural head on.

I cleared my mind of all preconceptions; grubby Rochdale cabbies passing white girls round for sex like a fried chicken bargain bucket, Imams beating kids into devotion, and the truly indoctrinated, blowing up Brussels to get 72 virgins in paradise.

…

It is them and us. And THEY have no wish to be anything like US.

It was good to see that the three top rated comments under her article were all sharp rebukes. However and – to quote Katie Hopkins – ‘it pains me to say it’ – her analysis, however nastily framed, is not completely wrong – the poll threw up some truly disturbing findings and these cannot be brushed aside.

However that’s just what the respondents quoted in this Guardian piece sought to do. It’s not that every point they raised was worthless – it’s more that they tended only to engage with the problematic findings in order to excuse them.

Many British Muslims hold traditional values that others of other faiths may hold such as disagreeing with same-sex marriage. Yet overwhelming evidence points to the fact that we are a patriotic community and have a strong affiliation and sense of belonging to this great nation.

If the only LGBT-related division raised by the poll was opposition to same-sex marriage there wouldn’t be so much concern. A sense of belonging and patriotism isn’t some kind of get out of jail card for being a bigot.

There’s more deflection in this crappy piece by comedian Aatif Nawaz – also an unengaging interviewee on the programme who thought that all that was needed to solve the antisemitism problem was to uncouple Judaism from Zionism.

How can it be possible that the views of 1,000 odd people can prove something about an entire community? According to the survey, half of all British-Muslims believe homosexuality should be illegal in the UK. I’m supposed to take ICM’s word for it? Because they were so right about the general election?

His conclusion was a string of non sequiturs

I made my points. Antisemitism is wrong. Homophobia is wrong. Misogyny is wrong. Surely in 2016 people can just take that as given? British Muslims are good people, so don’t buy into the scaremongering. Britain is better than that

Miqdaad Versi cleverly says the disquieting results mustn’t be swept under the carpet while doing just that.

These attitudes are not to be swept under the carpet, but are these issues high up on the agenda for British Muslims? The Muslim Council of Britain’s own research has shown that far more serious concerns relate to poverty, gender, criminality and Islamophobia.

I suppose it’s true that the situation would be still worse if say criminalising homosexuality was a major preoccupation for Muslims – I’m sure it isn’t – but how would Versi feel if a substantial proportion of Brits wanted to ban Islam, ideally, even though they were still more concerned by the problems facing the NHS?

Of course there were plenty of good responses as well as predictable kneejerk stuff from both sides. I’ve already linked to Iram Ramzan. Kenan Malik’s analysis was characteristically thoughtful, and Mohammed Amin offers some practical suggestions.

Normatives

While watching the programme I noticed a fair flurry of irritated tweets from liberal or liberalish Muslims who felt the programme was a bit souped up. This was an understandable enough response from secular Muslims who would like their own stance to be amplified where possible. However it’s been more difficult for our normative friends to know how to respond. How angry can they get over findings which (regrettably) demonstrate that many British Muslims take what they see as the correct line on a fair few isues?

Here’s a rather sulky response from iERA.

One of my favourite reactions is this from 5Pillars’ Roshan Salih:

‘These are crazy questions designed to catch Muslims out and make them look bad.’

Oh dear. He claimed that the questions about antisemitism weren’t asked of non-Muslims. But in fact they were, and the results for one question he mentioned – ‘do Jews have too much power in Britain’ – were certainly sufficiently divergent to merit comment. 9% non-Muslims agreed, compared to 35% Muslims.

Interestingly he doesn’t mention the fact that – leaving ISIS to one side – only 7% support the notion of a Caliphate.

Gene adds: You can watch the Channel 4 program (for now) here: