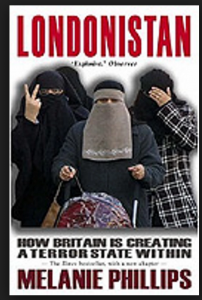

2016 sees the tenth anniversary of Melanie Phillips’ study of radicalism and extremism in the UK. Here follow a few thoughts on Londonistan from a 2016 perspective. I read the kindle edition, but a searchable text is available here.

Extremism and censorship

Although I have a number of reservations about the book, some detailed below, her key concerns about extremism seem fully earned. I agree with her premise, stated in the 2008 preface to the revised edition, that a narrow focus on violent extremism is inadequate, particularly when people whose views are themselves extreme are seen as suitable partners for government agencies in counter-terrorism work. Many of the groups, individuals and ideologies she tackles will be fully familiar to all readers of this blog. Have things got better or worse since 2006? David Cameron’s New Year’s message was robust, but it is hardly possible to report improvement within the Labour Party.

I also can’t fault her criticism of the supine (or worse) response from many to the Salman Rushdie and Danish cartoons episodes. I’m not sure how the reaction to the more recent Charlie Hebdo murders compares – certainly there was a very visible show of defiance from Western leaders and others, but that may be explained by the scale of the violence involved. Yet I think on balance some improvement can be noted. More people are aware of these issues, and some who initially railed against Rushdie have now, for whatever reason, stepped back from that position.

However I don’t think all her targets are equally legitimate. She warns of the rise of sharia-compliant finance, and notes two key problems with this practice: the fact it could be seen to legitimise sharia more generally and the possibility it might finance terror. No evidence is provided for the second anxiety, and my own view is that any aspect of ‘sharia’ (a broad term) that seems either neutral or benign should be left alone.

the establishment

Yet on the whole my reservations about the book were not prompted by thinking it anti-Muslim or even anti-Islam. She is impatient with those who insist that terrorism has nothing to do with religion, and with the grievance-mongering of figures such as Iqbal Sacranie, but avoids implying that Islam is irredeemably violent or evil, and acknowledges different strands within Islamic tradition. Her analysis of the relationship between Islamism and Islam is fair and precise. She certainly doesn’t ignore liberal, secular Muslim voices – although she wishes there were more of them. I was expecting more of a ‘Eurabian’ note in the book – ‘Londonistan’ and ‘Eurabia’ are somehow entwined together in my mind – but this concept was not to the fore.

It’s in her treatment of British authorities and institutions – the police, the legal profession, the intelligence services – that her arguments sometimes seem exaggerated, particularly when her gripe with the secularisation of society comes into play. Some of her concerns are reasonable – anti-Israel bias, the church’s tendency to ignore the persecution of Christians, cultural self-censorship, the turning of a blind eye to a succession of radical speakers in universities, and much else.

Yet although, to take just one of her targets, some of Phillips’ criticisms of the police are justified, she is wrong to simply dismiss the charge of ‘institutional racism’ levelled against them, and sneer at their efforts to improve their relationships with various minorities. However I sympathise with her impatience at police spokespeople trying frantically to keep Islam and terrorism apart, and with her condemnation of their dealings with the IHRC.

Her list of people getting things badly wrong is damning. For example Sir Colin Mccoll, the former head of MI6, stated in a 2004 lecture that what was needed was:

‘a new Islamist leader, both charismatic and positive, an Islamic Pied Piper who will take the young Muslims down a creative and non-violent path … Central to such an effort, of course, is a willingness to see published attacks on some of the sacred cows of western policy—the universality of western values, Israeli-tilted policies on nuclear proliferation and Palestine, western farming subsidies and the joys of globalization.’

secularism

Perhaps the oddest aspect of the book is the way its gloomy judgement on our ‘louche’ culture chimes with the perspective of her other key target, conservative Muslim thinking. She contends that Britain has become decadent, has adopted an ‘anything goes’ culture – and implies that its ‘moral squalor’ affronts Muslims and encourages them ‘to fill with an Islamist perspective the space that has been vacated by the collapse of Judeo-Christian moral authority.’ One of Phillips’ grumbles is the growing acceptance of homosexuality as a lifestyle on an equal footing to heterosexuality.The Press TV report on homosexuality, highlighted in wildcolonialboy’s recent post and presented by 5Pillars’ Roshan Salih, would presumably have Melanie Phillips nodding along in agreement. (I acknowledge, of course, that she completely opposes an Islamist stance on this issue.)

Ten years on, although Islamism hasn’t gone away, it’s good to note that Tell MAMA chose Peter Tatchell for a patron and that a gay Muslim peer played a key role in legalising gay marriage. And although Phillips seems to think the Judeo-Christian traditions need to be beefed up in order to save us from Islamism, since 2006 there has been a rise in the number and visibility of those opposing Islamism from a secular, often avowedly atheist perspective. Phillips talks of ‘secular nihilists’, which does a great disservice to the positive and passionately held views of many, perhaps in particular some of those with the weakest links to Judeo-Christian culture, the Muslim and ex-Muslim activists and bloggers who risk their lives in theocratic states.

Phillips implies that ‘militant gays’ helped Britain get used to subordinating majority values to minority rights. But this isn’t comparing like with like. Whereas gay rights protestors want equal rights and freedom from discrimination, Islamists (ultimately) want to impose their tastes on everyone else. Her parallel would only work if heterosexuals were being forced into same sex marriage. Her irritation at a ‘radical egalitarianism’ that insists that ‘all lifestyles were of equal value’, as well as being a bit of a straw man, echoes, albeit faintly, the grumbles of Islamists. However she is quite right to identify an unnatural alliance between some leftist progressives and Islamist conservatives and to note these groups’ shared attraction to anti-Israel rhetoric.

2006 responses

I found it interesting to remind myself how the book was originally received. My memory was of a more hostile response – more accusations of crude ‘Islamophobia’. David Smith, in the Guardian, offered a jaunty review, critical in places, but indulgent rather than hostile. Kenan Malik, who is cited respectfully by Phillips, offers a critique which is, in many ways, thoughtful and considered. Yet although I share most of his criticisms of the book, I think he brushes aside some of its better sections too quickly. And, although it’s certainly true that she never under-eggs, this is rather unfair:

If you want fear and hysteria, nobody does it better than Phillips. What we are facing, she tells us, is a war of the worlds between Islam and the West.

Compared to some ‘counterjihadists’ her take on the clash of civilisations idea is quite nuanced. And also he invokes ‘foolish attempts to reach out to moderate Muslims’ when what she deplores is trying to bring faux moderates on board as allies – a vital distinction.

Of course, as I’ve indicated, some elements of the book are absurd. Nafeez Ahmed, like me, was struck by her bizarre focus on ‘militant gays’

How can you take seriously someone who believes that:

1) The United Kingdom has been taken hostage by gays, no, not just gays, militant gays (gays with guns?, what the hell is that supposed to mean???), feminists and antiracists, no wait we have to put that in inverted commas, “antiracists”. Is she trying to describe the Blair Cabinet?

…

The logical implications of this totally bizarre set of axioms is that gays, feminists and antiracists are in the same boat as al-Qaeda terrorists.

This particularly egregious hostage to fortune on Phillips’ part enables Ahmed to skip lightly over the rest of the book, although he does quickly note that it might stir up anti-Muslim sentiment.

Similarly Peter Preston, while taking understandable issue with Phillips’ (implied) response to the murder of Stephen Lawrence, misrepresents the book quite badly:

Melanie Phillips, alas, acknowledges no such complexity in her ferocious denunciation of new London’s many faiths and traditions in Londonistan. Stephen Lawrence features here only as a watershed case that ‘paralysed the police for fear of giving offence to any minority group and being tarred with the lethal charge of prejudice’, the fount of our ‘victim culture’.

In fact Phillips makes a very genuine effort, as I’ve already noted, not to smear Muslims or essentialise Islam..

Closer to home, David T touched on Londonistan here ten years ago, asserting the worth of secular, liberal values.

Perhaps the worst review was this, by Brendan O’Neill in The New Statesman. Here he is on 7/7.

What Phillips presents as the handiwork of “clerical fascism” looks increasingly like Britain’s Columbine, a murderous stunt executed by four bored and overgrown adolescents who had nothing better to do.

He goes on:

Phillips’s exaggeration of jihadism betrays a bigger political oversight. She fails to understand that today’s handful of cranky extremists – who do occasionally launch scrappy, bloody attacks – express the demise of radical political Islam, not its re-emergence. Even the fact that some of these individuals have gathered in London exposes their weakness: there is nowhere else for them to go in a world that, since the Afghan- Soviet war, has become increasingly hostile to radical Islam.

Although there are things I take serious issue with in Londonistan, I think (a good deal of) what Melanie Phillips said in 2006 stands the test of time better than Brendan O’Neill’s scoffing.

I didn’t read Londonistan at the time. I have been trying to work out, inconclusively, whether or not my response to it would have been different ten years ago.