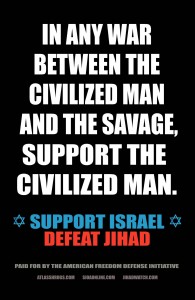

A federal judge has rejected Pamela Geller’s legal appeal against the Massachussets Bay Transport Authority (MBTA). This had been triggered by the MBTA’s refusal to display controversial pro-Israel subway advertisements, paid for by the American Freedom Defence Initiative. This was not primarily a free speech issue as the MBTA has clear guidelines which rule out much controversial material – for example sexually suggestive images. The judge, Nathaniel M. Gorton, had to consider whether the MBTA had followed its own procedures appropriately and consistently.

Officials with the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority rejected the ad in November on the basis that it violated the agency’s advertising guidelines, which include rejecting advertisements that demean and disparage individuals and groups, promote alcohol or tobacco, and depict graphic violence.

Specifically, it was asserted by the MBTA that the advertisement would demean and disparage Muslims and/or Palestinians. The full ruling can be read here, and subsequent page references refer to this pdf.

Although the MBTA guidelines are quite restrictive, they do not prohibit material of a politically controversial nature, although they won’t allow ‘false, misleading or deceptive commercial speech’. (Italics mine).

Two key questions here are: 1) were the advertisements demeaning and disparaging to Muslims/Palestinians and 2) Did the MBTA implement its guidelines consistently?

The ruling was quite nuanced on the first issue, as it acknowledged that the ads were susceptible to different interpretations:

Gorton said the advertisement’s wording was ambiguous and subject to interpretation. And the transit agency did not have to apply the best interpretation of the vague statement but only a reasonable one because the T advertising program is not regarded as a public forum. It was, therefore, “plausible for the defendants to conclude that the . . . Pro-Israel advertisement demeans or disparages Muslims or Palestinians.”

I’d put it a little more strongly myself, for the following reasons (all in fact acknowledged in the ruling). The poster seems to imply that all those who might be seen as opposed to Israel, or Israel’s policies, are savages, that Palestinians who have objections to Israel’s policies are all savages, potentially (p.14).

It could be argued that to use ‘jihad’ as a synonym for purely violent struggle distorts that word’s meaning, promoting violent stereotypes of Islam/Muslims (pp. 14-15). And it’s more problematic when used in this particular inflammatory context. ‘Savage’ has racial connotations – it implies a whole people rather than just individuals in the way a word like ‘thugs’ or ‘bullies’ might (pp.22-3).

The answer to the second question – did the MBTA implement its guidelines consistently? – also clearly seems to be ‘yes’. However it is necessary to pause on the fact that a pro-Palestinian poster campaign was allowed.

Clearly this poster is controversial and tendentious. If the guidelines had not specified that only misleading commercial speech should be prohibited, perhaps it should not have been allowed. It might have been necessary to spend more time weighing up the respective demerits of the two campaigns if the ruling had not revealed that some pro-Israel campaigns were approved. Stand with Us produced posters asserting that ‘Jews are indigenous to Israel’ and making robust counter-assertions about the size of Israel at various periods (p. 7). The fact that these posters were permitted strongly suggests that misgivings about the Geller ads were not driven by ideological bias.

Stand with Us was allowed to display this poster

linking to this site which asserts, inter alia, that Palestinian leaders promoted hatred and terrorism against Israel and the Jewish people (p.7) This material, like the pro-Palestinian maps, is politically controversial. But, as the judge correctly ruled, the Geller ads could be seen to go beyond mere controversy.