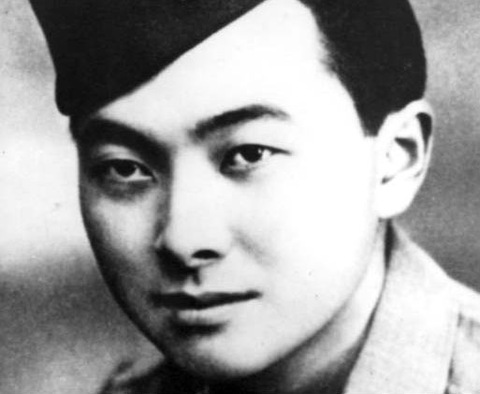

Daniel Inouye, a pro–labor, pro-Israel Democrat who represented Hawaii in the US Senate for nearly 50 years, has died at the age of 88.

Inouye was was one of only three veterans of World War II remaining in Congress. When his fellow Hawaii senator, Daniel Akaka, retires at the end of the year, there will be just one left.

Among other things, Inouye deserves to be remembered for his extraordinary bravery and sacrifice in the final days of the war against Nazi Germany.

In 1943, when the United States Army lifted its ban on Japanese-Americans, Mr. Inouye joined the new 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the first all-nisei volunteer unit. It became the most decorated unit in American military history. In 1944, fighting in Italy and France, he won a battlefield commission to second lieutenant. He was shot in the chest, but the bullet was stopped by two silver dollars in his pocket.

On April 21, 1945, weeks before the end of the war in Europe, he led an assault near San Terenzo, Italy. His platoon was pinned down by three machine guns. Although shot in the stomach, he ran forward and destroyed one emplacement with a hand grenade and another with his submachine gun. He was crawling toward the third when enemy fire nearly severed his right arm, leaving a grenade, in his words, “clenched in a fist that suddenly didn’t belong to me anymore.” He pried it loose, threw it with his left hand and destroyed the bunker. Stumbling forward, he silenced resistance with gun bursts before being hit in the leg and collapsing unconscious.

His mutilated right arm was amputated in a field hospital. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, which was upgraded to the Medal of Honor, America’s highest military award, by President Bill Clinton in 2000. (Members of the 442nd were believed to have been denied proper recognition because of their race.) He spent two years in Army hospitals, including one in Michigan where he met Bob Dole and Philip Hart, wounded veterans who would also become senators. Mr. Inouye was discharged as a captain in 1947.

Many of the 442nd’s members came out of the relocation camps to which Japanese-Americans on the west coast were sent after the attack on Pearl Harbor. As Doris Kearns Goodwin’s wrote in No Ordinary Time, her book about the Roosevelt administration during World War II:

[T]he number of Japanese Americans serving in the U.S. Army continued to grow, reaching thirty-three thousand. “I’ve never had more whole-hearted, serious-minded cooperation from army troops,” Lieutenant Colonel Farrant Turner said of the all-Japanese 100th Infantry Battalion, which fought with great distinction in Italy and France. The 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which also fought in Italy and France, was known as the “Christmas tree regiment,” because it became the most decorated unit in the entire army. In seven major campaigns, the combined 100th and 442nd suffered 9,486 casualties and won 18,143 medals for valor, including almost ten thousand Purple Hearts. In addition, more than sixteen thousand Nisei served in military intelligence in the Pacific, translating captured documents.

At Topaz, Manzanar, Poston, Heart Mountain, and other relocation camps, the parents of fallen heroes accepted the extraordinary honors on behalf of their sons. The color guard turned out as the medals of the dead were pinned on their mothers’ blouses. The familiar sadness of the ceremony was multiplied by its setting: a tawdry tar-paper barrack surrounded by strips of barbed wire which denied the parents of the honored soldiers the very freedom for which their sons had died.