Former Guatemalan military leader Efrain Rios Montt is finally being brought to justice for genocide and crimes against humanity.

Gen Rios Montt, 85, was in power from 1982-1983, when some of the country’s worst civil war atrocities occurred.

Whole villages of indigenous Mayans were massacred as part of government efforts to defeat left-wing rebels.

Gen Rios Montt, who has denied ordering massacres, refused to comment in court. But a judge ruled he had a case to answer, placing him under house arrest.

As a congressman, Gen Rios Montt had enjoyed immunity from prosecution for 12 years. The immunity was lifted on 14 January 2012, when his term in office ran out.

…..

[Prosecutor] Manuel Vasquez said he could present documents, videos and statements accusing Gen Rios Montt of “planning, designing and overseeing the military counter-insurgency plans against the indigenous population in Ixil de Quiche”.Mr Vasquez accused Gen Rios Montt of being behind 100 massacres in which 1,771 people were killed and 29,000 displaced.

…..

An estimated 200,000 people were killed or went missing during Guatemala’s civil conflict, which ended in 1996. Gen Rios Montt’s 17 months in power are believed to be one of the most brutal periods of the war.

Good. US backing for Rios Montt and other murderous rightwing strongmen in Guatemala, El Salvador and elsewhere in Central America during the 1970s and 1980s is a shameful part part of our history. (Then-president Ronald Reagan praised Rios Montt at the time as “a man of great personal integrity” who was “totally dedicated to democracy,” and dismissed charges of atrocities in Guatemala as a “bum rap.”)

Unfortunately the prospects of another despotic Latin American leader being tried for his crimes before his death are vanishingly small.

The repression began in the early years of the revolution when men, women and children accused of counter-revolutionary acts were thrown into prison. Sentences were long and living conditions harsh. Some who came to be known as plantados – the steadfast ones – refused to be treated as common criminals and remained naked rather than wear prison garb.

“They tried by every means to dehumanize people,” said José Pujals Mederos, a plantado who served 27 years and 22 days in jail. Prison officials retaliated against the plantados by denying them family visits, sometimes for years.

The plantados were also subjected to frequent beatings. Medical care and nourishment was scant. And the forced isolation from loved ones brought with it an overwhelming sense of loneliness.

“We would go for months without clothing,” said Jorge Valls, a plantado who spent 20 years and 40 days in prison. “We were naked cave men in a 20th century cave.”

Beyond the dehumanizing conditions, these political prisoners also lived with the constant threat of death. Valls remembers hearing executions being carried out nearly every night while he was held at the La Cabaúa prison in Havana.

British historian Hugh Thomas wrote in his 1971 tome on Cuba that “the total number of executions by the revolution probably reached 2,000 by early 1961, perhaps 5,000 by 1970 – But who can be certain of figures in this realm?”

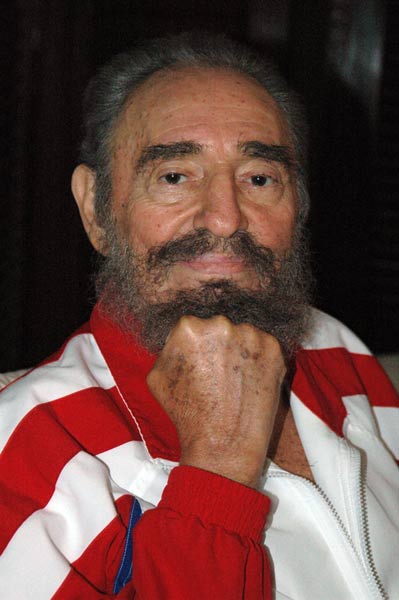

Of course some of the most outspoken opponents of the likes of Rios Montt are shameless apologists for the likes of Fidel Castro. And vice versa.