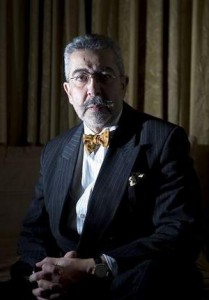

Here is Michel Massih QC, the barrister who is trying to get a court to issue an arrest warrant for Ehud Barak.

Although he is best known for his high profile defences of terrorists, from Abu Nidal gunmen, through the IRA and right up to Tanvir Hussain – now convicted of conspiracy to murder for his part in the ‘Airlines plot – he has quite an impressive international practice:

He is advising the Syrian government and military officials who are being investigated by the United Nations Security Council over the murder of Rafik Hariri, the former prime minister of Lebanon; and he is advising the president of Sudan, Omar al Bashir, who has been accused of presiding over genocide in Darfur by the chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court in The Hague.

As an English barrister, he is bound by the so called cab rank rule: that a barrister must accept any case for which he or she is available, as long as it is within his competence. That most barristers both prosecute and defend is one of the strengths of the English system – it prevents you from becoming too ‘prosecution’ or ‘defence’ minded.

There are, however, a few barristers who – for a variety of reasons – will only defend, and some specialist prosecution sets whose barristers largely only prosecute. For example, Treasury Counsel spend a period of their lives prosecuting serious cases, before moving back to general practice. And there are some sets – such as Massih’s own chambers, Tooks Court – some of whose members, originally at least, subscribed to a revolutionary socialist perspective on their profession, in which the barrister played the role of the insurrectionary. For them, refusing to prosecute as a political act. Once in a while, somebody like Michael Mansfield QC, will dabble in a spot of prosecuting: most unfortunately in the ill fated Stephen Lawrence private prosecution, the failure of which rendered it practically impossible to try in the future those who were suspected of that young man’s racist murder.

Here’s Massih’s perspective:

Over a cup of tea he explained that the relationship between client and barrister is a complex one. “If a lawyer defends an alleged rapist, that does not mean the lawyer identifies with the crime or the alleged criminal.

“The lawyer’s duty is to examine the evidence against the client, and then to confront the client with the evidence and to indicate the strength of the case. If, despite the lawyer’s advice, the defendant still maintains that he is not guilty, it is the lawyer’s duty to represent him or her fearlessly.”

…

Massih’s advocacy of bringing Israel to justice is both professional and personal. While he has been “instructed” as a barrister to pursue various warrants against Israelis over the years, his recent television appearances calling for legal action against Israel have been acts of his own volition. One might ask: If Massih is so outspoken about prosecuting Israel for its alleged war crimes in Gaza, how can he he help defend the president of Sudan, who is accused of war crimes in Darfur?

“There is no double standard in my accepting a brief for Sudan,” he says. “This is not something I sought out. I was instructed by a major international law firm. It is the same principle that applied to my application for arrest warrants against the Israelis; this is an area within my competence.”

Since Massih is, by trade, just a lawyerly cab driver waiting in a queue for clients that match his skills, an intriguing possibility comes to mind. As an expert in war crimes, would Massih be prepared to defend an Israeli general detained in Britain, if the brief landed on his desk?

I rang his mobile to get an answer to this question. Somewhat surprisingly, he was not in Khartoum or Damascus, but buying milk in a London supermarket. “The cab-rank rule is very important at the English bar,” he said. “In this case it’s a theoretical possibility.”

A theoretical possibility? For the Palestinian lad who found his voice haranguing the crowds at Speakers Corner? Surely not. Browsing through the aisles, Massih concluded his thought: “Of course, it’s not going to happen. No one is going to offer me that brief.”

Indeed.

I wonder what it is about Massih that makes him the counsel of choice for terrorists of various stripes, Syrian assassins and Sudanese genocidaires?

My guess is that it is pretty much the same quality which renders him anathema to those who he has made a career out of pursuing through the courts.

UPDATE

Of course, Massih’s scheme has failed.