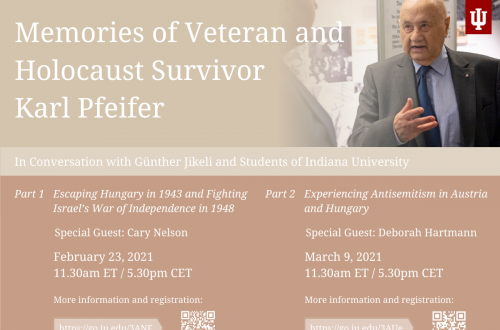

Bill Kristol, editor of The Weekly Standard (a leading journal of mainstream conservatism in the US), thinks the Confederacy and the people who fought for it have been getting an unfair rap in recent days.

The Left's 21st century agenda: expunging every trace of respect, recognition or acknowledgment of Americans who fought for the Confederacy.

— Bill Kristol (@BillKristol) June 23, 2015

If that is “the Left’s” current agenda, I haven’t been informed– although I can think of worse ones. I’ll simply note that those who fought for the states which seceded from the United States of America and became the Confederacy no longer considered themselves Americans as we currently understand the term. They considered themselves citizens of a separate and hostile nation dedicated above all to the preservation and expansion of human bondage. Traitors, you might even say.

Pity and sadness for many of the poor white non-slaveowners (the Virgil Caines) who fought for the Confederacy? Yes. Respect? Sorry, no.

(In fact the Confederacy’s draft law effectively exempted any man who owned 20 or more slaves, causing resentment among poor Southern whites. And more than 100,000 disillusioned Confederate soldiers had deserted by the end of the war. Those I can respect.)

But wait. There’s more:

It's our own mini-French Revolution, expunging history in a frenzy of self-righteousness. Luckily, so far: 1st time tragedy, 2nd time farce.

— Bill Kristol (@BillKristol) June 23, 2015

Expunging history? The real expunging of history occurred decades after the Civil War, when many white Southerners latched onto the idea that the Confederacy was not fighting for the right to continue enslaving black people, but rather for the noble principle of “states’ rights” against “Northern aggression”– and that the pre-war era was a golden age of simple-minded but contented slaves and benevolent masters (e.g. “Gone with the Wind”). It is only in more recent decades that a more honest history of the era has emerged.

Next, Left will ban teaching of Lincoln's Second Inaugural in schools. None of that "with malice toward none, with charity for all" stuff…

— Bill Kristol (@BillKristol) June 23, 2015

No, Bill. “Left” (as you understand it) will not ban the teaching of that great speech (as if it had the power to do so). Among other things, Lincoln made clear that the war started only because the South insisted on not only the preservation but also the expansion of slavery:

One-eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was somehow the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union even by war, while the Government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it.

Yet even as the war was coming to a close, Lincoln emphasized that the conflict would now end only with the utter abolition of slavery:

Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgements of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

“With malice toward none, with charity for all” was not a statement of respect for the enemy or the cause for which it fought. Rather it expressed a generous willingness not to treat the defeated Confederates as criminals or traitors.

That Kristol– an influential figure in Republican circles– fails to grasp what the war (led by the first Republican president) was all about indicates that his understanding of history is as sorely lacking as was his grasp of politics when he famously recommended that John McCain select Sarah Palin as his running mate in 2008.

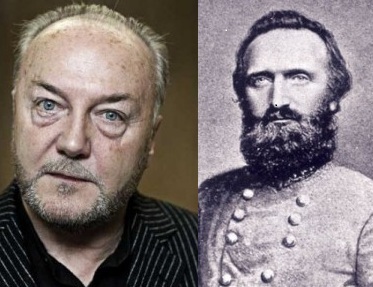

Kristol, however, may be pleased to learn that at least one self-identified man of the Left agrees that a leading Confederate is worthy of respect and recognition.

One surprising fact is that [George Galloway] is an American Civil War buff and that his favourite figure from that period is Thomas J Jackson, the Confederate commander known as Stonewall on account of his resolve in the face of the enemy. I came across a quote from Jackson, which I read to Galloway when I meet him in his Westminster office on a hot day in the week following the first London bombs: “A battle always had the effect of brightening my faculties and I always think more clearly, rapidly, and with more satisfaction in the heat of an engagement than at any other time.”

Galloway has never heard this before and looks astonished, although not, of course, lost for words. “That entirely applies to me,” he says. “Isn’t that extraordinary? Oof. It’s almost spooky. That’s a very, very profound connection…”

Spooky indeed.