A year or so ago, I was pretty sure that by this time, Syria’s dictator Bashar al-Assad would be out of power– dead or in exile.

The best explanation of why I (and others) were wrong about this is provided by Annia Ciezadlo writing in The New Republic. It’s a fascinating and insightful piece which anyone interested in the Syrian tragedy should read in full.

She tells how Assad managed to transform the perception and, to a large extent, the reality of the Syrian uprising from a struggle against brutal repression to a sectarian civil war in which the Syrian regime is portrayed as a secular bastion against the forces of violent jihad and Islamism.

One measure of Assad’s success is that the likes of George Galloway and John Wight have found common ground with the likes of Rand Paul and Glenn Beck.

I never doubted Assad’s capacity for murdering his own people in the tens of thousands. I did underestimate his cunning.

Update: As it appears few commenters have bothered to read the article in question, let me quote from the relevant part of it:

On March 30, 2011, as the conflict escalated, [Assad] gave a defiant and conspiratorial speech casting himself as the victim of “foreign powers” who had stirred up insurrection in a bid to destroy Syria. “They adopt the principle,” he said of his enemies, “of ‘lie until you believe your lie.’ ”

In fact, it is Assad who has done exactly that. Calmly and deliberately, he has painted a picture that in the beginning was not completely accurate: The demonstrators, he said, were jihadists who would bring Afghanistan-type chaos to the country. Then he sat back and waited for it to become true. “He’s very strategic. From the very first day, he was talking about terrorists and Syria’s national unity,” says a former regime official, who has now defected to the United States. “People were talking about democracy, human rights, silly stuff—not silly, but not strategic—and he is talking about Al Qaeda.”

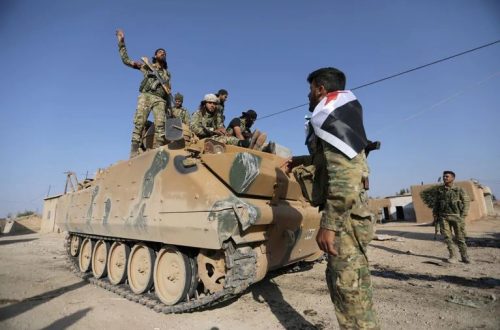

And if a series of well-timed massacres by the regime would provoke outrage in the West, Assad also knew that images of carnage would cause Gulf states to arm the Islamist opposition and escalate the sectarian warfare. This was his strategy: to make intervention so unpalatable that the international community would take no steps to alter the course of the conflict. “These jihadists who have come in, largely courtesy of private Gulf money, these are his enemies of choice,” says Frederic C. Hof, the Obama administration’s former envoy to the Syrian opposition and currently a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council. “I call it a coalition of co-dependency.”

As the Al Qaeda element grew stronger, the regime became increasingly aggressive at playing it up. With Islamist rebels seizing territory closer and closer to Israeli-occupied areas, the opposition posted a video of a half-dozen fighters driving along the border of the Golan Heights. “For forty years, not one shot has been fired against Israel from here,” one of the fighters shouts in Arabic. “Allahu akbar!” At that, some of his companions raise their Kalashnikovs with one hand and shoot them into the air. “The regime made sure that this video was all over [the Internet] the next day,” says the former Assad official. “They took their whole media machine and they put it everywhere, to show the Israelis: Look what’s coming.”

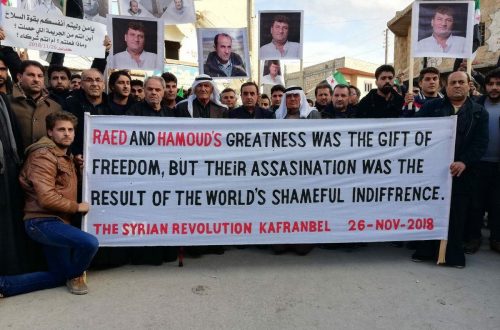

Meanwhile, the regime methodically discredited the revolution’s moderate, secular factions with sophisticated dirty tricks. For the first four or five months of the war, security forces treated detainees from Damascus with relative caution, even as they massacred villagers in rural areas—a shrewd way to make opposition claims of brutality look hysterical to the capital’s middle and upper classes. “If you were from a good family, they wouldn’t torture you,” says Mohamad Al Bardan, a nonviolent opposition leader who now lives abroad. “People like me, at one point, we felt they were stupid. They are not stupid at all.”

Further update: As I’ve noted in previous posts, I’m not letting Obama off the hook. His refusal to take strong action to aid the Syrian rebels when they were largely indigenous and secular helped produce the current state of affairs.