Nancy Salgado, a single mother of two young children and a 10-year employee of a McDonald’s restaurant in Chicago, confronted McDonald’s president Jeff Stratton when he spoke at a meeting of the Union League Club.

“Do you think it’s fair that I am making $8.25 [the hourly minimum wage in Illinois] while I’ve worked for McDonald’s for 10 years? Do you think it’s fair? My two kids are struggling because you can’t raise our minimum wage. I don’t believe that’s fair. What do you have to say?”

Strangely enough, Stratton could only reply, “I’ve been there for 40 years.”

Wow. And after all that time he earns only, um, never mind…

Salgado is an activist in the “Fight for 15” campaign, which calls for a $15 an hour wage for fast food and retail workers in Chicago. She is a devout Catholic who said she believes that God was with her when she spoke– a reminder that religion is not always the opiate of the masses.

Some have said that Salgado (who was arrested for her trouble) should have worked her way up the McDonald’s corporate ladder or found a better-paying job– which I suppose would be a good deal easier to do if you’re not a single parent with two kids. At any rate, I’m among those radicals who believe that anyone who gets up every day and goes to work at a not-very-fun job deserves to earn more than poverty wages.

The Washington Post reports:

For years, the fast food industry was one of the “100 percent turnover” industries: Businesses that started the year with one workforce but would entirely replace it–at least once, if not more–by year’s end.

But that ratio has been creeping steadily downward. A report in QSR, the “quick-service restaurant” industry’s major trade publication, shows that turnover was as high as 120 percent in early 2009, but dropped to around 90 percent in 2011. A spokesperson for the National Restaurant Association says its 2010 Operations Report puts employee turnover at “limited-service” restaurants at just 60 percent. Meanwhile, figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that turnover in the “accommodations and food services” industry was 84 percent in 2001 but dropped to 61 percent by 2012, slightly higher than the nadir in 2010 of 57 percent. Those numbers include restaurants and businesses that pay more than the fast-food industry–so they’re likely lower than for those who truly hold “McJobs”–but they also show a general decline.

There’s an obvious reason for the drop: Unemployment. When it’s low, it’s harder to get people to stay in jobs, particularly low-wage ones. When it’s high, it’s easier, and turnover drops. The older ages of fast food workers are also surely having an impact on turnover, too: With roughly 80 percent of the industry’s workforce now older than 20, they’re more likely to be in need of steady employment and less likely to be seeking jobs for temporary periods of time.

Contrary to the idea some have of fast food workers being overwhelmingly teenagers earning spending money, in fact:

• Almost 40 percent of fast food workers are 25 or older.

• More than 30 percent have at least some college experience.

• More than a quarter are parents.

In an even-handed look at wages in the fast food industry, Time’s Christopher Matthews makes the case that fast food restaurants are not sharing their success with their employees:

The fact is, franchise financial data is private, and even if McDonald’s and its franchises are wildly profitable, it may not say that much about the overall health of the restaurant industry. But looking at aggregate data from Sageworks, a private-company financial-data analytics firm, shows that private fast-food firms are doing quite well these days, and that they’re not sharing their profits with workers. According to Sageworks data:

• Profit margins for privately held fast-food companies are 4.6%, up from 2.1% in 2009

• Revenues over the past year are up 12.1%, following a 8.4% increase the previous year

• The percentage of revenue spent on payroll has decreased from 23.5% to 22.9%

That being said, a profit margin of 4.6% isn’t huge. At least, it’s not the sort of profitability that would allow most firms to double their wages. But it does show that whatever success these companies are having, they aren’t sharing it with employees.

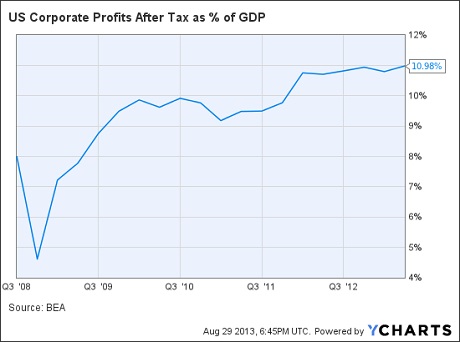

And this isn’t just a problem with the fast-food industry. This comes at a time when wages have been almost completely stagnant. And corporate profit margins across the board have soared in recent years, while the median worker’s pay has stayed flat.

Regardless of how profitable McDonald’s is or isn’t, it’s clear that in the aggregate, many businesses could afford to pay their workers more. Can you really blame fast-food workers for realizing this fact and trying to force their bosses to share some of corporate America’s good fortune?