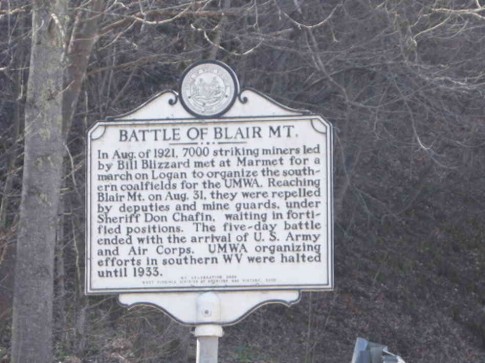

In August and September of 1921 during the Battle of Blair Mountain— “the largest armed rebellion since the American Civil War”– West Virginia coal miners faced off against local, state and federal law enforcement and agents of the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency, acting on behalf of coal company operators during an effort by the United Mine Workers to organize miners in the southern part of the state.

The battle was triggered by the assassination by Baldwin-Felts agents of Sid Hatfield, the pro-miners union sheriff of Matewan, West Virginia. Hatfield had become a hero to miners when he stood up to Baldwin-Felts agents the previous year in what became known as the Matewan Massacre, after the agents evicted the families of pro-union miners from coal company housing– as depicted in the 1987 movie “Matewan.”

According to the West Virginia Division of Culture and History:

On August 20, 1921, nearly five thousand miners, armed with rifles and an old machine gun with three thousand rounds of ammunition, assembled at Marmet. Their commander, “General” Bill Blizzard, a twenty-eight year old man of proven leadership in [United Mine Workers] District 17, formed the men into a column and began the march toward Logan. Along the way new recruits swelled the column until it reached fifteen to twenty thousand men…. Realizing that two years of cumulative “insurrectionary fury” were about to explode in the coalfields, Governor Morgan, on August 25, asked President Warren Harding for one thousand troops and military aircraft. According to Morgan “the miners had been `inflamed and infuriated by speeches of radical officers and leaders’.”…

At midnight, August 27, 1921, in an ill-advised move to arrest leaders of the miners’ march and union miners involved in a recent fracas with state police, a posse of from seventy to one hundred deputies and state police, led by Sheriff Don Chafin and Captain James Brockus, went to the small mining community of Sharples north of Blair Mountain, near the Boone County line. In a confrontation with miners that resulted in a gunfight, at least two miners were killed and two others were wounded. From positions on adjacent hillsides, miners fired at the police forces who quickly withdrew. Within forty-eight hours, five thousand miners streamed back into the area to defend their homes against what they perceived as a new and unwarranted attack by those in league with the coal operators. Miners who were awaiting trains to return to their homes from the aborted march on Logan County now refused to board, and resumed their march. Chafin and Brockus, in an effort to contain and combat the new uprising, raised a volunteer force of approximately three thousand anti-union, anti-miner “militiamen,” and took up positions near the summit of nearby Blair Mountain. With the miners deployed along a ten-mile front at the base of the mountain, determined to wipe out all impediments to their march, Governor Morgan on August 29 renewed his application for federal troops, citing an insurrection fanned by the influx of “Bolshevist” outsiders from Indiana, Ohio, and Illinois…

…On August 30, Harding issued a proclamation under RS 5300 as the first step toward federal intervention to protect West Virginia from domestic violence. The proclamation called for both the miners and the Logan County force to disperse by noon on September 1, 1921. It was the first such presidential proclamation regarding a civil disorder issued since the American entry into World War I four and one-half years before. The proclamation finally and formally put to rest the wartime policy of direct access in action as well as thought…

On September 1-2, intermittent skirmishing took place as the miners probed the positions of the defending force. Not content with rifle and machine gun fire to repulse the miners, the coal company operators associated with the Logan County force at one point arranged for commercial aircraft to drop homemade bombs filled with nails and metal fragments upon the miners. The bombs missed their targets or failed to explode…

Army Air Corps planes flew reconnaissance over the scene of the battle, but did not use ammunition against the miners.

The miners, reassured then that they would not be attacked, and unwilling to resist so many regulars and the power of the national government, surrendered to the federal troops or simply went home. Although casualty figures were not kept by either side, best estimates put the death toll during the Battle of Blair Mountain at sixteen with all but four of the dead being miners. None of the casualties were inflicted by federal forces.

Between September 4-8, 1921, federal troops disarmed and sent home without incident nearly fifty-four hundred miners… Military intelligence agents investigated union headquarters and meeting halls for evidence linking the marchers to a radical conspiracy. The agents found almost no radical literature, in spite of coal operator claims, and determined that a mere 10 percent of the miners were foreigners, “poor ignorant creatures who will believe anything that they are told.”

UMW officials and members of the “miner’s army” display a bomb dropped on them during the Battle of Blair Mountain

UMW officials and members of the “miner’s army” display a bomb dropped on them during the Battle of Blair Mountain