“The most dangerous untruths are truths moderately distorted.” – Georg Christoph Lichtenberg

Yesterday I read a comment complaining that there was too much ‘propaganda’ above the line at Harry’s Place. I assume this was a reference to articles the reader didn’t agree with, but propaganda comes in all shapes and forms, and you may be less likely to call it by that name if you approve of the message it’s trying to promote.

If you are in London over the next couple of months, this exhibition at the British Library is well worth a visit. It traces developments in propaganda from Roman times to the present day, with much material from China, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. As well as propaganda designed to boost national pride or demonise the enemy, the exhibition includes softer propaganda – promoting healthy eating or road safety for example. There’s a huge amount to take in here – including clips from propaganda films and mini documentaries/interviews addressing the different issues. The exhibition seemed designed to expand our sense of what constituted propaganda, and particularly to draw our attention to propaganda which we may not recognize either because it is subtler or because, broadly, we are in tune with its aims. It was interesting to see examples of propaganda from opposing sides juxtaposed together, and to be able to reflect on the many continuities between the propaganda of different eras and regimes. A picture of the statue of liberty with sinister spies peering out of her eyes (produced in the Soviet Union) seems echoed in the way today’s least free regimes are quickest to see gaps in the USA’s commitment to liberty.

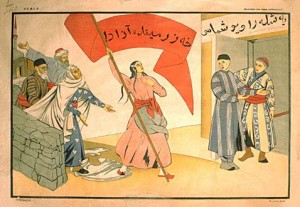

Exhibits which stuck in my mind included this eyecatching picture of a girl from one of the central Asian Soviet republics whose dress and demeanour signal that she has been liberated from religious restrictions. Her conservative family seem to be imploring her to abandon her modern ways, while two young men look at her with apparent shy admiration. It was also very intriguing to see beautiful Iranian paintings, postcard sized, depicting the evils of Hitler and supporting the allied powers. Propaganda dropped in Iraq back in 2003 looked bizarrely dated, as though the artist was consciously copying earlier twentieth-century styles. One is perhaps less likely to be familiar with the propaganda produced by one’s own country or ‘side’, and there were many examples of US and UK propaganda on display, ranging from dehumanizing portrayals of the enemy in WWI to exhibits relating to the recent Olympic Games in London.

One of the best videos was an interview with a spokesman from the Holocaust Educational Trust, drawing attention to the ways in which antisemitic propaganda mutated to suit the prevailing political conditions – the association between communism and Jews, for example, was not made when relations were more cordial between Germany and the Soviet Union. Clips of propaganda films produced in Nazi Germany were, not surprisingly, some of the most disturbing exhibits.

The exhibition closes on 17 September.