L-R: Anna, Lili, Heinz, Heinrich

2013 will mark the 75th anniversary of the Anschluss, when Hitler annexed Austria and the Nazis overtook the country, welcomed by the Austrian populace. As a consequence of this move, my “Weissman” (we have lost one “n” in translation) family has been in the United Kingdom for three generations, as my grandmother Lili would take the Kindertransport train from Vienna to London Liverpool Street.

When she boarded the train destined for London, aged 14, she remembers seeing children on the platform who had missed this train. They told each other that they would take the next train out of Austria.

The next train never came. My grandmother would never see her family again. Her fatherHeinrich Weissmann was murdered in Buchenwald, on December 12th 1939. Her mother Anna Weissmann was murdered in Sobibor, along with her little brother Heinz, in June 1942.

They were taken to Sobibor in the Transport 27. Adolf Eichmann had arranged for the “final solution” to be expanded throughout the Third Reich, to include Jews in Vienna, who would not be informed of their pending transfer until six days before the event, so as to curb the spread of news throughout Jewish communities.

Jews were instructed to meet at Klein Sperlgasse 2 in Vienna, where there was then a Jewish school. Now I don’t know what there is there, apart from a furniture shop round the corner. There the Central Office for Jewish Emigration registered deportees. Yad Vashem explains:

Sometimes as many as 2,000 people waited at the school for days, even weeks, to be deported. They would sleep on the floor or on straw sacks. Sanitary conditions at the school were understandably abysmal and reflected the state of mind of the people waiting to be expelled. Some people suffered nervous breakdowns; others committed suicide. The two doctors and two nurses on site did their best to ease the situation. While they waited at the gathering point, the Jews would undergo a registration procedure called “Kommissionierung”, which was often accompanied by violence. The staff of the Central Office for Jewish Emigration in Vienna, among them Anton Brunner, would force the Jews to declare all their property before signing a document confirming that they were transferring everything they owned to the state. The Jews were also forced to hand over to Central Office representatives all the valuables and cash they had on their persons. The Gestapo then went on to sell all confiscated Jewish property.

Just as Lili’s train was the last from Vienna to London, Transport 27 was the last train from Vienna to Sobibor.

Transport number 27 departed on June 14, 1942 at 07:08 pm from Aspangbahnhof in Vienna in a train marked Da 38 and arrived at the Sobibor extermination camp in Poland on June 17 at 08:15 am and not, as previously planned, at the township of Izbica. The transport contained 1,000 Jews and included the eminent ethnologist, Eugenie Goldstern. 267 persons in the transport were older than 61 years, and the average age was 50 years.

An armed fifteen-man Schupo detail, including two sergeants, Hauer and Bittermann (their first names are unknown), under the command of Lieutenant Joseph Fischmann (Revierleutnant der Schutzpolizei) of the police number 1 special reserve unit, was appointed to guard the transport. The policemen reported at the train station at 11:00 am in accordance with an order issued by Alois Brunner of the Central Office for Jewish Emigration. The Jewish deportees were led to the train station from the assembly point at which they had been held and embarkation began at 12:00 am, under the supervision of members of the Central Office for Jewish Emigration, SS-Obersturmfuehrer Alois Brunner and SS-Hauptscharfuehrer Ernst Girzick, who were present at the site. The process took place without any resistance or disturbance. At 4:00 pm checks were made to ensure that all the deportees were indeed on the train.

The train traveled a route that took it from Vienna through Breclav (Lundenburg), Brno (Bruenn), Nysa (Neisse), Opole (Oppeln), Czestochowa (Tschenstochau), Kielce, Radom, Deblin, Lublin and Cholm to Sobibor.

At 1:45 pm on June 15 the train crossed the border into the General Government. At 21:00 on June 16, 1942, the train stopped at the train station in Lublin. In accordance with an order issued by SS-Obersturmfuehrer Helmut Ortwin Pohl, who was present at the site, a selection was carried out on the deportees and fifty-one able bodied men aged between fifteen and fifty were taken off the train and sent to the Majdanek concentration camp. A sum of 100,000 zlotys was confiscated from the Jews and transferred to Pohl’s custody, as were the three freight cars – containing the deportees’ personal belongings, which were separated from the train. These were unloaded at the Trawniki labor camp some 30 kilometers from Lublin and handed over to SS-Scharführer Mayershofer. At 11 pm the train continued on its journey, with the 949 Jews on board who had been left behind after the selection; it drew in at the Sobibor extermination camp on June 17, 1942 at 08:15 am. On its arrival, responsibility for the transport was transferred to the camp’s commandant, SS-Oberleutnant Franz Stangl. Disembarkation of the deportees began immediately. All the Jews on the transport from Vienna were murdered as soon as they arrived at Sobibor. This transport was the last one to leave Vienna for the province of Lublin.

When they returned to Vienna, the officer and the two sergeants who had accompanied the train handed in an expense report. For guarding the Jewish deportees and for their journey back to Vienna, they were paid 260 Reichsmark.

Franz Stangl oversaw the murder of my great-grandmother and my great uncle, little Heinz.

At his trial in 1970, he admitted responsibility for the murder of 900,000 Jews, adding:

“My conscience is clear. I was simply doing my duty.”

Christian churches protested Stangl’s murder of the mentally handicapped by gassing them, and so Hitler put an end to this practice. The murder of Jews in gas chambers would continue.

Stangl’s family ended up in Syria, and then Brazil, where he was eventually apprehended. He would be sentenced to life imprisonment in 1970, and die the following year of a heart attack.

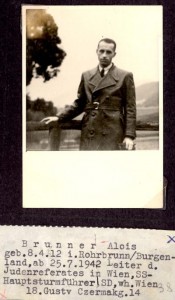

This is Alois Brunner who helped to place my family members on trains:

Brunner escaped justice to live in Syria, as reported last year in the IB Times.

When Anna and Heinz arrived at Sobibor, they were likely met by the Preacher. The Preacher was Hermann Michel. He had a warm and pleasant voice, wearing a white coat, and standing on a balcony to greet Jews.

This is what my family would have heard upon arriving at Sobibor – survivor Ada Lichtman explains:

We heard word for word how Oberscharfuhrer Michel, standing on a small table, convinced the people to calm down. He promised them that after the baths all their belongings would be returned to them and that it was time for Jews to become a productive element. At present all of them would be going to the Ukraine to live and work. This address aroused confidence and enthusiasm among the people. They applauded spontaneously and sometimes even danced and sang.

Here is an eye-witness SS account, also found on Michel’s Wikipedia page, of the Preacher’s message to my family:

“ Before the Jews undressed, Oberscharführer Hermann Michel made a speech to them. On these occasions, he used to wear a white coat to give the impression [that he was] a physician. Michel announced to the Jews that they would be sent to work. But before this they would have to take baths and undergo disinfection, so as to prevent the spread of diseases…. After undressing, the Jews were taken through the so-called Schlauch (“tube”). They were led to the gas chambers not by the Germans but by Ukrainians…. After the Jews entered the gas chambers, the Ukrainians closed the doors…. The motor which supplied the gas was switched on by a Ukrainian called Emil and by a German driver called Erich Bauer from Berlin. After the gassing, the doors were opened, and the corpses were removed by a group of Jewish workers…”

The entire project was overseen by Odilo Globocknik, who was responsible also for the extermination of all Polish Jewry.

You should watch this interview with Meier Ziss, who entered the camp in the same month as my family did. The rest of his family was sent to the gas chambers in Sobibor upon arrival. Meier Ziss had to burn the passports and documents of Sobibor victims, and oversee the luggage. He was appointed ‘chief fireman’. Were a worker to get sick, he would be shot at the lazaret at Sobibor.

One SS guard at Sobibor was John Demjanjuk. Demjanjuk was a “lowly” guard at Sobibor, and his trial and conviction in 2011 marked the first occasion in which a guard was found guilty of complicity in spite of his lowly rank. Ignat Danilchenko claimed to have seen Demjanjuk herding Jews to their death.

A Jewish Holocaust survivor who entered Sobibor the following year, described the horror of the camp at the Demjanjuk trial:

Mr Blatt has not been able to identify Demjanjuk as having been one of the 100 Ukrainian guards at the camp, although he believes he was certainly there at the time he was a Sobibor prisoner. His testimony will nevertheless make it chillingly clear that anyone employed as a Sobibor guard was a vital cog in the machinery of genocide. “We were terrified of the Ukrainian guards at Sobibor. They were worse than the Germans – and I was there at the same time as Demjanjuk,” he said.

Mr Blatt was born in Izbica, only 43 miles from the Sobibor death camp. A Nazi SS squad picked him up with his father, mother and young brother during a routine “Jew round-up” in April 1943. They were bundled into a truck. “The camp gate opened to reveal what looked like a beautiful village,” he said. “We had heard what went on in there, but we refused to believe it. But I knew better, I was 15 and I realised that I was going to die,” he added.

He remembers a man standing next to him peering through a hole in the truck’s side at a group of Ukrainian guards equipped with bull whips. The man said, in Yiddish, how the place was “black” with them in reference to their black SS uniforms. Within a matter of seconds the Jewish prisoners were herded out of the truck and set upon by the screaming, whip-wielding guards who drove them up a path known as the “Himmelfahrtstrasse” or “road to heaven” towards the gas chambers.

“They mistreated us, they shot the old and the sick new arrivals who couldn’t walk anymore. And they were the ones who drove the naked people into the gas chambers with their bayonets. They would come back with splashes of blood on their boots,” Mr Blatt told The Independent on Sunday. “I often had to work a few feet away. If they refused to go on, they hit them and fired shots. I can still remember their shout of ‘Idi siuda’, which means ‘come here’,” he added.

Young Thomas saw his father being beaten with a club.”Then I lost sight of him. I said to my mother, ‘And yesterday I wasn’t allowed to drink the rest of the milk, because you absolutely wanted to save some for today’. That strange remark of mine still haunts me today – it was the last thing I said to her. My brother stayed at my mother’s side. They were all murdered in the gas chambers within the hour.” A few weeks later, Thomas Blatt was forced to watch his best friend, Leon, being slowly beaten to death.

Middle-class Dutch Jews started being sent to Sobibor shortly after his arrival and the SS changed their tactics to trick them. “When a Dutch transport arrived, usually an SS man would hold a speech. He would apologise for the arduous journey, and said that for hygienic reasons, everyone needed to shower first. Then later they would be given jobs. Some of the new arrivals applauded. They had no idea what was in store,” he recalled.

He survived only because the SS had executed a number of so-called “work Jews” at Sobibor the day before he arrived. The camp commandant was looking for replacements and 15-year-old Thomas pushed himself forward, pleading “Take me, take me!”.

His jobs included polishing SS men’s boots, sorting the clothes and shaving the hair off naked women prisoners before they were driven into gas chambers pumped full of exhaust fumes. It took up to 40 minutes for those inside to die. “We heard the whine of the generator that started the submarine engine which made the gas that killed them. I remember standing and listening to the muffled screams and knowing that men, women and children were dying in agony as I sorted their clothes. This is what I live with,” he said.

Demjanjuk died in March 2012.

Am Yisrael Chai.