This is a guest post by Adam Barnett

Not least among this year’s myth-busting events and revelations is the discovery of Osama bin Laden’s journal, which was retrieved from his Abottobad HQ. While we look forward with interest to seeing what else the U.S.’s harvest of ‘the Osama diaries’ yields, one common fallacy at least can join al Qaeda’s Amir in being truly sunk.

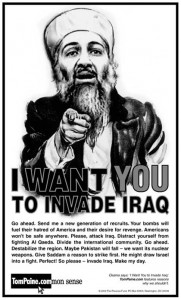

It has long been the licensed opinion that ‘western’ intervention in Iraq to dethrone Saddam Hussein was precisely what bin Laden wanted, as it would provide him with a propaganda tool with which to recruit new Jihadists. This ‘theory’, sometimes attributed to the racist and liar Abdul Bari Atwan, was even applied by some to the war against al Qaeda and its Taliban hosts in Afghanistan. Anyone following the debates over these actions will have heard this argument being made, and will have registered the weird confidence of its promulgators.

So it’s rather a blow to this ‘theory’ that bin Laden’s desperate scribbles were reportedly focused on the best means of achieving an American withdrawal. Instead of hoping western powers would send troops and planes his way, he appears to have become convinced that only a replay of September 2001, (his proudest achievement, or ‘greatest hit’), would give al Qaeda the breathing space to operate. It’s actually a testament to the resolve of his enemies that no amount of suicide-murder would force them to scuttle from the battlefield. (Bin Laden had been banking on American cowardice following ‘the collapse of American morale’ in Somalia, from which he concluded that its defeat would be easier than that of the Soviet Union.

Indeed, withdrawal has been a running theme in al Qaeda statements, and for reasons beyond its vulgar aversion to infidel shoes on ‘Muslim’ soil. When western clever-clogs would attribute exploding commuter trains in Europe to the fact that troops were ‘occupying’ space in ‘the Muslim world’, in a way they were correct. As this week’s news demonstrates, bin Laden has been wondering how many dead civilians would provoke a coalition surrender too. However, his calculations are not motivated by a sentimental attachment to holy sand alone, but are politically strategic. Al Qaeda, (or ‘the Base’), is currently rootless, and would dearly love a less-than-stable country from which to train death squads and plot attacks.

In the death of bin Laden, western leaders see a pretext for a ‘draw-down’ of troop ‘levels’ in Afghanistan, against the advice of their generals . To abnegate their responsibilities in this way would be to offer him a posthumous victory; it would be to reward him in death with the very prize denied him in life.

Of course, a strategy is not correct simply by virtue of bin Laden’s opposition to it, and there is much to argue over on how best to proceed. The government in Kabul is not the most reliable or virtuous of allies, and the liberties of the women of Afghanistan must be protected and extended regardless of the political allegiance of those seeking to negate them. However, any attempt to disengage from the region – thus ignoring our security concerns and humanitarian obligations, which have been earned through bad policies and paid for in blood – would be unpardonable. After all this noble sacrifice, we must not allow bin Laden to become a martyr to his cause.