Last December, as we approached Christmas and the New Year, I wrote that one reason to be thankful during the holiday season was that:

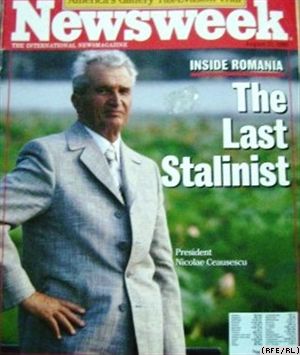

Socialist Unity has not (yet) published a semi-nostalgic look back at the regime of Romanian Communist dictator Nicolae Ceausescu, who was toppled from power and executed 20 years ago this month.

Unfortunately we won’t have that to be thankful for this coming holiday season.

Yes, you guessed it: Socialist Unity has republished a rose-colored-glasses look back on the Ceausescu era from Calvin “Zin” Tucker’s 21st Century Socialism. It’s based in part on a poll which– like a lot of polls in Eastern European countries– finds some longing for the supposedly “good old days” of Communist rule.

Granted, when times are hard– as they have been for too many people in post-Communist Romania– there’s a tendency to remember previous eras as better than they actually were. But perhaps a better measure of Romanians’ attitudes is the result of last year’s presidential election, when Constantin Rotaru, candidate of the Socialist Alliance Party (now the Communist party) received all of 0.45 percent of the vote. The party holds no seats in the Romanian legislature.

You can learn about the supposedly golden Ceausescu era– including his draconian efforts to increase Romania’s population by outlawing contraception and abortion– at this website.

“The fetus is the property of the entire society,” Ceausescu proclaimed. “Anyone who avoids having children is a deserter who abandons the laws of national continuity.”

It was one of the late dictator’s cruelest commands. At first Romania’s birthrate nearly doubled. But poor nutrition and inadequate prenatal care endangered many pregnant women. The country’s infant-mortality rate soared to 83 deaths in every 1,000 births (against a Western European average of less than 10 per thousand). About one in 10 babies was born underweight; newborns weighing 1,500 grams (3 pounds, 5 ounces) were classified as miscarriages and denied treatment. Unwanted survivors often ended up in orphanages. “The law only forbade abortion,” says Dr. Alexander Floran Anca of Bucharest. “It did nothing to promote life.”

Ceausescu made mockery of family planning. He forbade sex education. Books on human sexuality and reproduction were classified as “state secrets,” to be used only as medical textbooks. With contraception banned, Romanians had to smuggle in condoms and birth-control pills. Though strictly illegal, abortions remained a widespread birth-control measure of last resort. Nationwide, Western sources estimate, 60 percent of all pregnancies ended in abortion or miscarriage.

The government’s enforcement techniques were as bad as the law. Women under the age of 45 were rounded up at their workplaces every one to three months and taken to clinics, where they were examined for signs of pregnancy, often in the presence of government agents – dubbed the “menstrual police” by some Romanians. A pregnant woman who failed to “produce” a baby at the proper time could expect to be summoned for questioning. Women who miscarried were suspected of arranging an abortion. Some doctors resorted for forging statistics. “If a child died in our district, we lost 10 to 25 percent of our salary,” says Dr. Geta Stanescu of Bucharest. “But it wasn’t our fault: we had no medicine or milk, and the families were poor.”

Abortion was legal in some cases: if a woman was over 40, if she already had four children, if her life was in danger – or, in practice, if she had Communist Party connections. Otherwise, illegal abortions cost from two to four months’ wages. If something went wrong, the legal consequences were enough to deter many women from seeking timely medical help. “Usually women were so terrified to come to the hospital that by the time we saw them it was too late,” says Dr. Anca. “Often they died at home.” No one knows how many women died from these back-alley abortions.