A Baader-Meinhof member is in court over a murder carried out in 1977. This cold case had been re-activated following DNA evidence from a letter claiming responsibility for the murder:

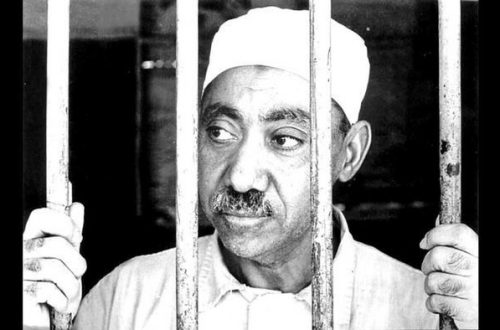

With her eyes hidden behind large black sunglasses, Verena Becker, 58, refused to comment on accusations that she played a part in shooting West Germany’s top prosecutor 33 years ago.

Siegfried Buback and his chauffeur died immediately when a motorbike pulled up next to their Mercedes as it waited at traffic lights and the pillion passenger opened fire with an automatic weapon in the southwestern city of Karlsruhe.

The attack, in which a third person in the limousine died from his injuries a few days later, marked the start of the “German Autumn,” the peak of the gang’s reign of terror which was to shake the country to its core.

An editorial [£], which I suspect chimes with the views of Oliver Kamm, notes the lessons of that counter-terrorist strategy.

There is a crucial lesson in this German experience of the 1970s. It was not that the methods of terrorist violence corrupted an idealistic message: on the contrary, a corrupt message dictated terrorist methods. The real libertarian and anti-fascist struggle was not to rationalise violence, but to inject sinew into the campaign to defeat it.

The anti-Semitism of the terrorist Left was revealed when a radical group bombed a Jewish hall in West Berlin in 1969 — on the anniversary of Kristallnacht. Horst Mahler, an RAF activist, supported the massacre of Israeli athletes by a radical Palestinian group at the Munich Olympics in 1972 — and is today a prominent neo-Nazi.

There is division in British politics today over anti-terrorist legislation. That debate had its forerunner in Germany in the 1970s. There remains disagreement about how far the liberties of terrorist suspects should be abridged; a draconian response can undermine security and liberal values. Yet a generation ago, Germany, with a terrible past but a new democratic culture, chose to defend itself and crack down on the RAF.

The outcome is illustrated in Ms Becker’s trial. She is an isolated figure of public curiosity rather than an heroic figure of the popular imagination. The defeat of her cause owes much to the ability of democratic politicians to agree on an essential principle: a free society requires the State; and the State must be able to defend itself. All other political goals depend on it.

While there is a general concensus that the previous Labour administration had not reached the right balance between civil liberties and security, there have also been too many instances of kneejerk opposition to measures to improve security – even in some cases a flagrant refusal to accept any risks exist in some circles. The coalition no doubt had a rude awakening once they came into office and were briefed about the risks they are now responsible for controlling. It is essential that they be given the space to ensure threats from violent extremists (the far right, Islamist groups, Northern Ireland or other radical groups) can be countered.